AUSTRALIA

In a nation of migrants the media faces its own identity crisis

By Christopher Warren

Australia is a country of migrants, a diverse, multi-cultural society with about 28 per cent born overseas in 200 countries and a further 20 per cent having at least one parent born overseas. Net migration drives up population by about 200,000 a year, with 800,000 arriving in the past four years.

Yet this story is largely absent from the Australian media which, in both news and entertainment, too often acts as though it is telling stories about and often to only one segment of society.

But as mainstream media fractures and social media spreads, political-elite consensus on race is breaking and journalism is being challenged. And as asylum seekers filter in, their use as a political tool demands new understanding and new ways to inform our communities. Yet the usual journalist focus on conflict means the real migration story of a society absorbing and adapting to change is missing

Codes and ethics: A missing link

This absence of the migration story is reflected in the codes of ethics and conduct that define the practice of journalism. At best, they adopt the language of non-discrimination. The Journalist Code of Ethics, developed and monitored by the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance, the journalists’ union, says: “Do not place unnecessary emphasis on personal characteristics, including race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, age, sexual orientation, family relationships, religious belief, or physical or intellectual disability.”

“Real Australians” by Alberto licensed under CC BY 2.0

Australia is a country of migrants, a diverse, multi-cultural society with about 28 per cent born overseas in 200 countries and a further 20 per cent having at least one parent born overseas. Net migration drives up population by about 200,000 a year, with 800,000 arriving in the past four years.

Yet this story is largely absent from the Australian media which, in both news and entertainment, too often acts as though it is telling stories about and often to only one segment of society.

But as mainstream media fractures and social media spreads, political-elite consensus on race is breaking and journalism is being challenged. And as asylum seekers filter in, their use as a political tool demands new understanding and new ways to inform our communities. Yet the usual journalist focus on conflict means the real migration story of a society absorbing and adapting to change is missing

Codes and ethics: A missing link

This absence of the migration story is reflected in the codes of ethics and conduct that define the practice of journalism. At best, they adopt the language of non-discrimination. The Journalist Code of Ethics, developed and monitored by the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance, the journalists’ union, says: “Do not place unnecessary emphasis on personal characteristics, including race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, age, sexual orientation, family relationships, religious belief, or physical or intellectual disability.”

There were similar words in the general principles of the Australian Press Council (which oversees print and on-line publications), although these were deleted in a 2014 rewrite, relying instead on advisory guidelines on reporting of race. Although the Press Council says it receives a significant number of complaints about reporting on race or ethnicity (often in the context of overseas events), most are resolved through mediation.

The codes of conduct for newspapers in the Fairfax group make no reference to these principles, except to the extent that they incorporate the MEAA code. The News Corporation code says: “Do not make pejorative reference to a person’s race, nationality, colour, religion, marital status, sex, sexual preferences, age, or physical or mental capacity. No details of a person’s race, nationality, colour, religion, marital status, sex, sexual preferences, age, or physical or mental incapacity should be included in a report unless they are relevant.”

Commercial electronic media are governed by codes of practice overseen by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). These provide a higher test: “[…] likely to incite hatred against, or serious contempt for, or severe ridicule of people on the grounds of, among other things, race or religion.”

The code of editorial practice for the national public broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), says: “Avoid the unjustified use of stereotypes or discriminatory content that could reasonably be interpreted as condoning or encouraging prejudice.” It also imposes a positive obligation to seek out and encourage reporting of diversity of views and experiences.

Other than this ABC reference to diversity, these ethical principles reflect the absence of reporting on migration. To the extent they have been discussed by ethics or conduct panels, it has been in the context of indigenous Australians or the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Similarly, the only major case against a journalist under Australia’s racial vilification laws involved questioning the Aboriginality of indigenous activists.

Sometimes it seems journalism lacks an accepted word to describe third-generation Australians – half the population – or a word to capture all the diversity of first- or second-generation Australians, or even those of multiple generations from non-English-speaking backgrounds.

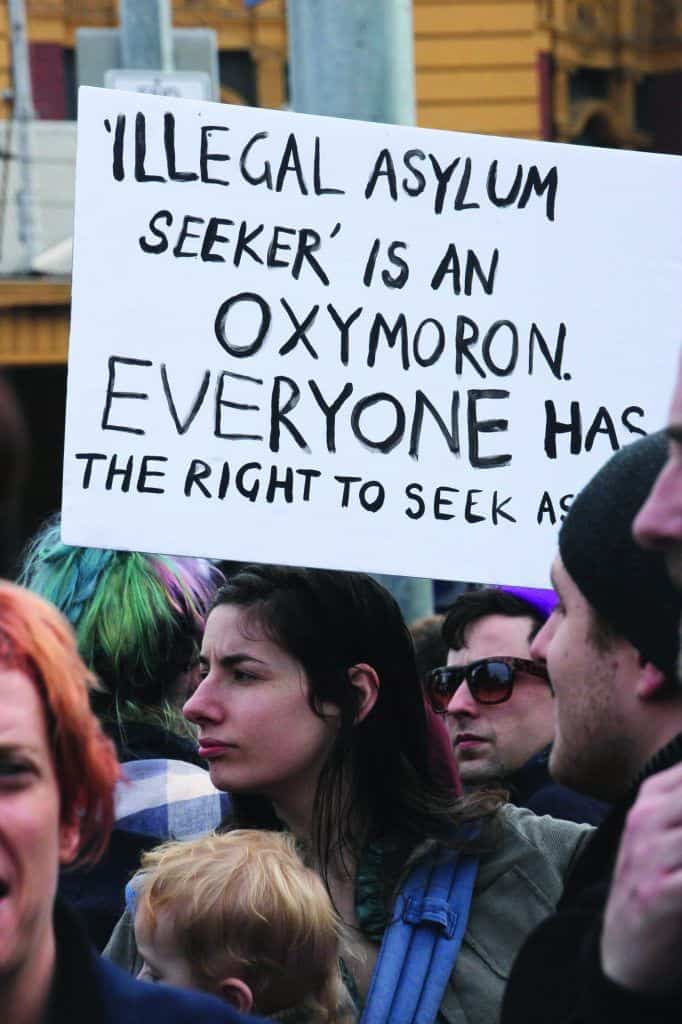

“Illegal asylum seeker is an oxymoron” by Takver licensed under CC BY 2.0

Even “Australian” can mean different things in different contexts: from third-generation people of British or Irish descent through to native-born Australians of all backgrounds and on to all residents. Because the different usages are so sensitive, most journalists use the term only in its broadest sense.

Journalistic style and practice has not adopted the use of the word “migrant” to mean first- or second-generation Australians. It is usually only used in referring to those involved in the act of migration itself. Once resident, there is no journalistically accepted word that captures the diversity of the once-were-migrants.

There have been some attempts by Australians from non-English-speaking backgrounds to appropriate the abusive word “wog” as a collective noun for themselves, but it is too freighted for general or journalistic use.

As a general principle, journalists are more careful in using “asylum seeker” or “refugee” so that usage generally accords with legal status. Despite attempts by some politicians to tag asylum seekers as “illegals” or “illegal migrants” this has not been adopted. The Australian Press Council has said use of these words could breach their principles and should be avoided.

The media workforce itself often seems a modernised pastiche of pre-1945 Australia, talking to and about itself. How does it change to more effectively represent the wider society? Failure to do so over decades means lack of coverage is a system flaw.

As Filipino-born Australian writer Fatima Measham wrote recently: “To put it bluntly, lack of diversity is not a symptom of exclusivity in Australian media; it is the disease. The status quo essentially reflects a form of denialism.”

Australia lacks clear statistics about its media community. Industry mapping by MEAA in 2005 indicated that about 9,000 people earned a living as journalists, most in or for newspapers and other print media. MEAA estimates there are now about 6,500.

The search for diversity

The only comprehensive study of ethnicity and migrant background in the media was conducted over 20 years ago. John Henningham of the University of Queensland found that mainstream journalists were overwhelmingly Australian-born with the remainder usually native to New Zealand or Britain. About 85 per cent said they were of either British or Irish descent

Anecdotal and personal observations indicate that there has been some shift in this pattern as second- or third-generation descendants of post-war migration from continental Europe (Italy, Greece, the former Yugoslavia etc.), or Asia, that began with Vietnamese migration in the 1970s, washed into journalism. Journalists have become younger, more female and, perhaps to a limited extent, more diverse. New employment has virtually collapsed since 2008 and, as a result there has been little renewal within the traditional mainstream.

“Tattoos and Islam” by Michael Coghlan licensed under CC BY 2.0

There is no evidence of deliberate discrimination by employers, although Henningham did find that about half of all journalists thought being from an ethnic or racial minority made it hard to get ahead.

In 2012, the ABC announced a commitment to greater cultural diversity in its news operations and seems to have succeeded. As a government authority, it is required to provide regular figures on employment. Its most recent report shows that among “content makers” (overwhelmingly journalists) 8.3 per cent were from non-English-speaking backgrounds, significantly lower than elsewhere in the corporation.

The report confirms that ABC International was one of the major employment areas for people from non-English-speaking backgrounds, including off-shore local hires. The closure of its international television service, Australia Network, in 2014 means this percentage has probably dropped.

Other than within the ABC, the decline in media employment has meant an even greater decline in opportunities to enter the mainstream business. It is unlikely that we will see a more diverse media emerge from some sort of affirmative action plan. Nonetheless, publishers and broadcasters need to follow the model of the public broadcasters in developing diversity policies and publicly reporting their progress.

New media – particularly those unaligned with traditional Australian or global media – are showing the greatest diversity, with people building their own opportunities and distribution networks. Journalism institutions need to examine how to support emerging media that encourage creative opportunities for a diverse Australia.

There is already significant evidence that changing the diversity of the journalist community changes what journalists consider news and changes how societies are reported. The feminisation of journalism since the 1960s has changed the reporting of gender, although there remains a long way to go.

Anti-migration racism

Australia is not constant and both assimilates and is assimilated by the successive generations of migrants. Racism is not absent and is usually directed at the most recent arrivals. Although almost all migrant communities can trace roots back to the earliest days of European settlement, the composition of the Australian community has been shaped by successive waves – European and Chinese migration in the gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s; the largely British and Irish migration (coupled with active exclusion and expulsion of Asian migration) from the 1880s to World War One; southern and eastern European immigration in the 1950s and 1960s; Vietnamese migration in the 1970s; Chinese and other East Asian migration in the 1990s, now joined by people from the Middle East and South Asia.

“Refugee Action protest” by Takver licensed under CC BY 2.0

The media has largely ignored the cultural and social impact of these events, unless they break into the political discussion of the day such as when a group is seen as (or is portrayed as) an existential threat to Australian society. Chinese migration and communities in the late 19th century were targeted by mobs and the law and largely excluded. Sectarianism directed at Irish Catholic communities was taken so much for granted that it was not reported.

Until the 1970s, Asian migration was largely blocked through the so-called White Australia policy which sought to restrict immigration to Europeans. This was abandoned by successive governments between 1965 and 1975 and then smashed by the large-scale Vietnamese migration. Since then, Asian migration has dominated. Other than Britain and New Zealand, four of the top five other birthplaces of Australians are Asian – China, India, Vietnam and the Philippines.

In the major cities where most media are based this change is even more obvious, with Asian-born Australians making a larger proportion of the population.

More recently there has been a shift in migration to Muslims from the Middle East and South Asia, coupled with the growth of asylum seekers. There has also been a degree of soft racism directed at most recent arrivals but the debate over Muslim migration has taken a new, decidedly harsher, edge.

In the Firing Line: Muslim and Middle East Migrants

As Australia opened up in the 1970s, Muslim and Middle East migration increased. As a result, the five-yearly census shows the number of Muslims has more than tripled over 20 years, from about 148,000 in 1991 to about 476,000 in 2011 – about 2.2 per cent of the total population. Although Muslims are a significant component, this percentage is not expected to rise above 3 per cent.

This community reflects the broad regional, national and religious diversity of Islam, although the largest groups are from Lebanon, Turkey and, more recently, Iraq and Afghanistan. As in much of the developed world, the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington affected approaches to the Muslim community. In Australia, this fed into a climate of antagonism against the latest arrivals.

This continues as part of the discourse on Islam, and shapes a key area of continuing debate: the right to religious freedom and the rights of women. The media continue to struggle with this as most journalists prioritise the rights of women. Some – largely but not exclusively on the right – continue to focus on women’s rights both within Islamic communities and in writing about the impact of Islam on women’s rights generally.

Many journalists avoid the issue of Islam to prevent being seen as encouraging attacks on Muslims.

Social media have played some role in filling this gap. Muslims – particularly women wearing the hijab – reported increased harassment on public transport after a siege in a Sydney cafe by an Iranian-born gunman claiming affiliation with ISIS in December 2014. This spawned the #illridewithyou hashtag on Twitter and other social media. Using this hashtag, about 150,000 people offered to travel with Muslims fearful of harassment.

But social media have also played a less constructive role. As tensions between the local community and mainly Lebanese groups escalated into riots at Cronulla beach in southern Sydney in 2005, text messaging promised “Leb and wog bashing” and also that “Aussies will feel the full force of the Arabs”.

Traditional media also contributed. In the week before the riots, talkback radio host Alan Jones fed the hysteria, saying to one caller: “We don’t have Anglo-Saxon kids out there raping women in Western Sydney”. While cautioning against people taking the law into their own hands, he read one of the text messages encouraging people to go to Cronulla for “Leb and wog bashing” on air and claimed credit for the building pressure in Cronulla.

Jones was subsequently censured by the ACMA for breaching the Code of Conduct with comments that were “likely to encourage violence or brutality and to vilify people of Lebanese and Middle-Eastern backgrounds on the basis of ethnicity”.

The riots suited all morality tales in the migration debate. For those hostile to migration, or Islamic migration in particular, it fed a narrative of the collapse of social cohesion. To others, it fed entrenched racism.

In fact, since the riots – perhaps as a result – public anti-migrant displays have eased and become more marginalised. There remains ongoing low-level commentary in some right- wing political circles and media and, of course, on social media, about Islam.

Here, concerns rumble on about halal and the wearing of the headscarf, without often breaking into the mainstream media which, generally, have ignored these debates.

There has been some serious reporting of the political groups behind these views. The Australian, News Corp’s national newspaper, has reported on and analysed fringe political groups such as Reclaim Australia, and the ABC’s 4 Corners devoted a programme to the anti-halal movement.

It is difficult to gauge how deep social antagonism is, but it does appear, with some caveats, that in the decade since the Cronulla riots, Muslim migrants have become incorporated into the Australian diversity. The most recent social cohesion survey by Monash University found that 58 per cent of Australians found the immigration intake – already at its highest levels – as about right or too low and 85 per cent said they believed multiculturalism was good for the country.

At the same time, about one in four said they had negative attitudes about Islam, though this may be more hostility to religion than to Muslim migrants.

Rise of ISIS and national security

The emergence of Islamic state and its recruitment of foreign fighters has provided a further opportunity for demonising the Muslim community. Government briefings suggest that about 150 Australians have sought to fight, although there is no clear evidence of this, and there have been reports that a number have been killed.

Information is largely based on briefings by security agencies and government, although the use of social media by ISIS and some individual fighters has also fed into media reporting.

Notoriously, Khaled Sharrouff, who had been convicted of domestic terrorist offences, fled with his family to Raqqa in Syria. From there, he tweeted a photo of his seven-year-old son holding the head of a murdered Syrian soldier.

Coming shortly after the videoed murders of US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, this shocking image raised the issue of whether the media should repeat or link to these images. Most carried pictures of the child with the face obscured. Most videos have not been carried or linked.

This incident was used by the government to justify increasing national security laws, including criminalising visits to designated areas (including northern Iraq and Syria) without good cause, and the administrative power to strip citizenship from dual nationals considered to be supporting terrorism.

However, integration of national security and Muslim migration has not always been a winning issue for governments. In 2007, The Australian newspaper’s Hedley Thomas won the country’s most prestigious journalism award for his reports on the security forces’ handling of the detention of Dr Mohamed Haneef for suspected terrorism. His reporting resulted in Haneef being released and cleared of all suspicion. It also undermined much of the government’s stance on the threat of terrorism.

Over the past two years the government has ramped up the rhetoric, raising the risk of terrorism to high and continually referring to ISIS as the “Daesh death cult”. In August, it was reported that the cabinet had directed that weekly announcements on national security would be rolled out between then and elections due in September 2016.

The first of these again sought to link migration and national security when the new militarised Border Force announced it would be cooperating in Operation Fortitude with the Victorian police in checking papers to identify “visa fraud” in Melbourne.

A social media campaign under the hashtag #Borderfarce threatened civil disobedience (Australians are not required to carry papers or to produce them on request) and resulted in a demonstration outside the press conference to promote the operation. The police withdrew cooperation and the operation was cancelled. This fed into a general media questioning of government competence.

“Manus Island regional processing facility” by Global Panorama licensed under CC BY 2.0

The challenge of covering asylum seekers

The enduring challenge is of asylum seekers arriving by boat, which has become a high-level media and political issue. Over the past 10 years, about 50,000 have arrived by boat; according to the Australian Parliamentary Library, most were legitimate refugees. Within the largest group, from Afghanistan, between 96 and 100 per cent were found to be legitimate refugees and were granted citizenship.

Yet it is on such asylum seekers (known as Irregular Maritime Arrivals) that politics and media are fixed. This dates back to the October 2001 national election, when the then conservative government launched a major campaign against what it saw as the escalation of boat arrivals (then about 2,500 a year).

When a Norwegian cargo ship, MS Tampa, rescued 438 mainly Afghan asylum seekers from a sinking boat and attempted to offload them on an Australian island, the Federal Government refused to allow them to enter territorial waters and subsequently seized the ship. The asylum seekers were then transferred to offshore detention centres on Papua New Guinea and Nauru as part of what became known as “the Pacific solution”.

Under the slogan “We will decide who enters this country and the circumstances in which they come”, the government, which was thought to be facing defeat in light of unpopular domestic policies, was comfortably re-elected.

The media generally took a sceptical approach to the rhetoric and the policy. In the run-up to the election, The Australian reported that government claims of asylum seekers deliberately throwing their children overboard to force the Australian Navy to rescue them were false and were known to government ministers to be false.

More disturbingly for journalists, community opposition to asylum seekers seemed to fracture their confidence that media opposition to racism and support for an open Australia reflected the views of society.

After the election of the Labour Government in 2007, the Pacific solution was abandoned. However, two years later there was an increase in asylum seekers, peaking at 18,000 in 2012-2013. It also raised concerns about deaths in the crossing from Indonesia, with about 600 drowning. Reporting on the deaths may have raised empathy for migrants while also acting as a deterrent to others wanting to travel.

The conservative opposition campaigned strongly under the slogan “Stop the Boats”. The re-introduction of offshore processing in the last days of the Labour Government and an increase in boats being turned back under the Liberal Government elected in 2013 seemed to close the ocean route.

However, the policies of the new government raised new challenges for journalists.

First, the process of maritime interception was militarised under the title Operation Sovereign Borders. As such, the government refused to reveal any details of “water matters”, saying any information would only assist people smugglers.

So media have had to seek information from asylum seekers themselves, including those still in or returned to Indonesia, to get any details on the actions of the Australian forces. As a result, such reporting is attacked by the government and its supporters as undermining the military.

Second, there remain about 150 asylum seekers (many now officially recognised as refugees) who arrived by boat and who continue to be detained on Papua New Guinea and Nauru. While journalists have sought to expose the deplorable conditions they are held in, they have generally been unable to get to them. Visas have become difficult to obtain and access to detainees is largely blocked.

Although it does not have an unblemished record, the Australian media has played a key role in building and sustaining social cohesion faced with this latest wave of migration. Social media have increasingly played a role in mobilising support for migrant communities. Despite government attempts to create a sense of fear and panic over the threat of domestic terrorism, the media has not played along.

However, the fracturing of the mainstream media has provided space for anti-migrant and, specifically, anti-Muslim voices. And again, social media has enabled these voices to be amplified.

It may be too early to tell if Australia has now absorbed the Muslim migration as it has earlier migrations. However, increasing diversity within the media, coupled with opportunities for new voices in new and social media, mean journalists will be better placed to manage the inevitable tensions of a diverse, multi-cultural society.