Moving Stories: International review of how media cover migration

Moving Stories is the Ethical Journalism Network’s international review of how media cover migration.

Introduction

By Kieran Cooke and Aidan White

Migration is part of the human condition. Ever since humankind emerged out of East Africa it has been on the move – searching for a better climate, looking for supplies of food and water, finding security and safety.

Migration has suddenly jumped to the top of the news agenda. In 2015 journalists reported the biggest mass movement of people around the world in recent history.

Television screens and newspapers have been filled with stories about the appalling loss of life and suffering of thousands of people escaping war in the Middle East or oppression and poverty in Africa and elsewhere.

Every day in 2015 seemed to bring a new migration tragedy: Syrian child refugees perish in the Mediterranean; groups of Rohingyas escaping persecution in Myanmar suffocate on boats in the South China Sea; children fleeing from gang warfare in Central America die of thirst in the desert as they try to enter the US.

“A Cry for Those in Peril on the Sea” by A. Rodriguez/UNHCR licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

In response to this crisis, the Ethical Journalism Network commissioned Moving Stories – a review of how media in selected countries have reported on refugees and migrants in a tumultuous year. We asked writers and researchers to examine the quality of coverage and to highlight reporting problems as well as good work.

The conclusions from many different parts of the world are remarkably similar: journalism under pressure from a weakening media economy; political bias and opportunism that drives the news agenda; the dangers of hate-speech, stereotyping and social exclusion of refugees and migrants. But at the same time there have been inspiring examples of careful, sensitive and ethical journalism that have shown empathy for the victims.

In most countries, the story has been dominated by two themes – numbers and emotions. Most of the time coverage is politically led with media often following an agenda dominated by loose language and talk of invasion and swarms. At other moments the story has been laced with humanity, empathy and a focus on the suffering of those involved.

What is unquestionable is that media everywhere play a vital role in bringing the world’s attention to these events. This report, written by journalists from or in the countries concerned, relates how their media cover migration.

They tell very different stories. Nepal and the Gambia are exporters of labour. Thousands of migrants, mostly young men, flock from the mountain villages of Nepal to work in the heat of the Gulf and Malaysia: often the consequences are disastrous. People from the Gambia make the treacherous trip across the Sahara to Libya and then by boat to Europe: many have perished on the way – either in the desert or drowned in the Mediterranean.

In these countries reporting of the migration of large numbers of the young – in many ways the lifeblood of their nations – is limited and stories about the hardship migrants endure are rare. Censorship or a lack of resources – or a combination of both – are mainly to blame for the inadequacies of coverage. Self-censorship, where reporters do not want to offend either their media employer or the government, is also an issue.

The reports on migration in China, India and Brazil tell another story. Though large numbers of people migrate from each of these countries, the main focus is on internal migration, a global phenomenon often ignored by mainstream media that involves millions and dwarfs the international movement of people.

What’s considered to be the biggest movement of people in history has taken place in China over the last 35 years. Cities are undergoing explosive growth, with several approaching 20 million inhabitants. Similar movements are happening in India and, to a lesser extent, in Brazil.

In Africa the headlines focus on people striving to leave the continent and heading north, but there is also migration between countries, with many people from the impoverished central regions heading for South Africa – a country where media also deal with problems of xenophobia and governmental pressure.

In Europe migration and refugee issues have shaken the tree of European unity with hundreds of thousands trekking by land and sea to escape war and poverty. The reports here reveal how for almost a year media have missed opportunities to sound the alarm to an imminent migration refugee crisis.

Media struggle to provide balanced coverage when political leaders respond with a mix of bigotry and panic – some announcing they will only take in Christian migrants while others plan to establish walls and razor wire fences. Much of the focus has been on countries in South Eastern Europe which has provided a key route for migrants and refugees on the march. In Bulgaria, as in much of the region, media have failed to play a responsible role and sensationalism has dominated news coverage.

In Italy, a frontline state where the Mediterranean refugee tragedy first unfolded, the threat of hate speech is always present, though this is often counterbalanced by an ethical attachment of many in journalism to a purpose-built charter against discrimination. In Britain the story has also often been politically driven and focused, sometimes without a sense of scale or balance: this has been particularly evident in reportage of the plight of refugees in Calais.

In Turkey, seen by many European politicians as a key country in stemming the onward rush of migrants, most media are under the thumb of a government that punishes dissident journalists, so the public debate is limited.

Like their Turkish colleagues, journalists in Lebanon live with the reality of millions of refugees from war-torn Syria within their borders which makes telling the story more complex and it is not helped by confused mixing of fact and opinion by many media.

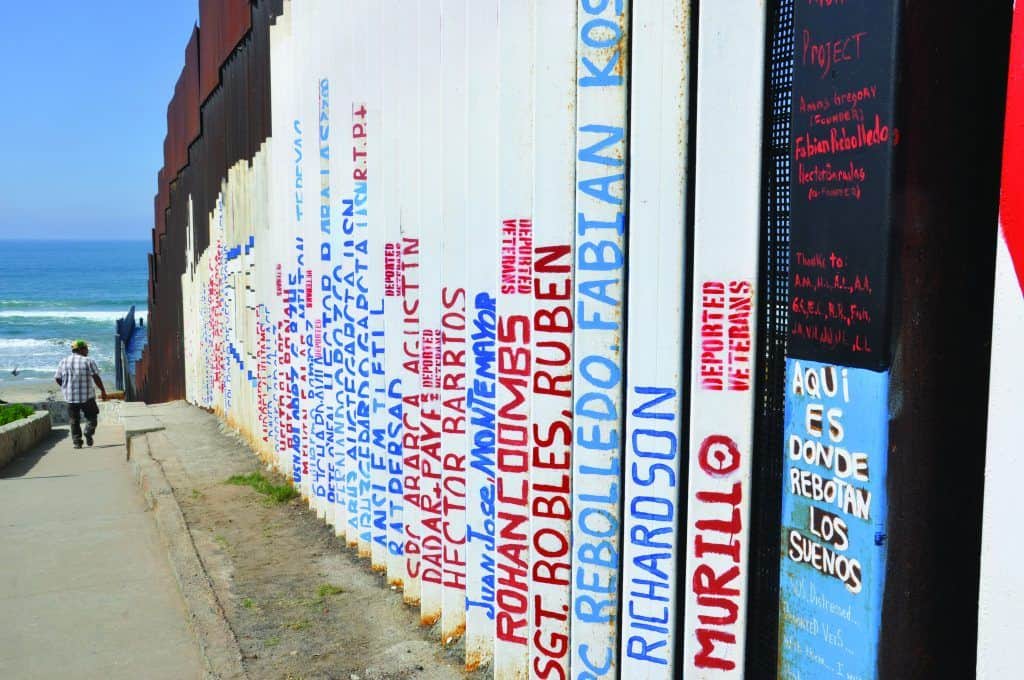

“Border fence at Friendship Park, Tijuana” by BBC World Service licensed under CC BY 2.0

At the same time in the United States media have helped make the migrant and refugee issue an explosive topic in debates between Republican Party candidates for the presidency. Media time has focused on heated and often racist exchanges. This has obscured much of the good reporting in some media that provides much-needed context. South of the border, in Mexico media also suffer from undue political pressure and self-censorship.

In Australia the media in a country built by migrants struggles to apply well-meaning codes of journalistic practice within a toxic political climate that has seen a rise in racism directed at new arrivals.

These reports cover only a handful of countries, but they are significant. The problems of scant and prejudicial coverage of migration issues exist everywhere. Even reporting of migration in the international media – with a few notable exceptions – tends to be overly simplistic.

Migrants are described as a threat. There is a tendency, both among many politicians and in sections of the mainstream media, to lump migrants together and present them as a seemingly endless tide of people who will steal jobs, become a burden on the state and ultimately threaten the native way of life.

Such reporting is not only wrong; it is also dishonest. Migrants often bring enormous benefits to their adopted countries.

How would California’s agricultural industry or the Texan oil fields survive without the presence of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Central American workers, often labouring on minimal wages? How could the health service in the UK continue without the thousands of migrant nurses and doctors from the developing world? How would cities like Dubai, Doha or Singapore have been built without labourers from Nepal or Bangladesh – or how would they function without the armies of maids and helpers from the Philippines and Indonesia?

These reports underscore why media need to explain and reinforce a wider understanding that migration is a natural process. No amount of razor wire or no matter how high walls are built, desperate migrants will find a way through. People will still flock to the cities, drawn by the hope of a better life.

The migrant crisis is not going to go away: the impact of widespread climate change and growing inequality is likely to exacerbate it in the years ahead.

The inescapable conclusion is that there has never been a greater need for useful and reliable intelligence on the complexities of migration and for media coverage to be informed, accurate and laced with humanity. But if that is to be achieved we must strengthen the craft of journalism.

Download the report

Browse the report by chapter