Case Study: Journalism, Hate-Speech and Terrorism

Aidan White

The difficulties facing traditional journalism are not just about finding ways to deal with the outrageous statements of rogue politicians, but also in handling the coverage of even more unscrupulous players – those who deal in hatred and terror.

In the digital age it is astonishingly easy for people to put their messages – in text, audio or video – online and for all to see. Among them are tech-savvy extremists who produce and circulate the propaganda of terror and war and who are ruthless in their exploitation of the communications opportunities provided by the Internet. And very often news media assist them in the process.

The use by traditional media of screen-grabs or footage of barbaric executions video films posted on the Internet by the propaganda cell of Daesh, also known as Islamic State, raises questions about the role of media in covering terrorism.

These brutal and bloodthirsty films including decapitations, shootings, and burning people alive can be viewed uncensored by anyone with access to the worldwide web and who knows where to look. But when they use the material, even in a sanitised form, do media help Daesh achieve their propaganda objectives?

It’s a question that worries many inside journalism who know that groups like Daesh have two audiences – one that they wish to shock and intimidate and a second that they wish to inspire. Their objectives are to strike fear into the heart of communities with whom they are at war and at the same time to radicalise and recruit to their cause alienated and restless young men and women.

In recent years many news media across all platforms of journalism have published images from the literature and videos of terrorist groups on their web and mainstream platforms with too little consideration of the potential impact.

Too often it seems media have been unaware or have ignored how the production and dissemination of horrific violence in the name of Jihad is in terrorists’ hands and they are ruthless in their use of the public relations opportunities that digital technology provides.

While the impact of the propaganda output of Islamic State is difficult to quantify, their video clips are attractive to media users. They are sophisticated and slick in their production and stemming the flow of such material provides a serious challenge to policymakers, particularly those trying to counter the threat of radicalisation of young people.

Belatedly some media have decided to act. Recognising the propaganda trap facing them and noting how Islamic State have recently used films produced by lone attackers in Germany and France pledging allegiance to the cause of violent Jihad, media in France have decided to take action to deny further publicity to these individuals.

Several news organisations including the influential daily Le Monde announced in July 2016 that they would stop publishing photos of people responsible for acts of violence and terrorist killings.

They said it was to avoid giving “posthumous glorification” to people responsible for brutal killings who want to be seen as heroes and whose notoriety may encourage fresh individuals, psychologically disturbed or not, to follow their lead.

There is no suggestion here that the press should cover up the truth; terrorist outrages must still be reported. And it is immaterial that images and names of the perpetrators of violence will appear on social media.

This a principled step by editorial leaders to eliminate unintended collusion with terrorism which is welcomed by many in journalism, but it does nothing to answer the question of how to stem the flow of propaganda material to social media outlets.

Those who seek death and glory will continue to have their stories told online and there will still be an audience to celebrate their actions no matter how brutal they are.

The question facing journalists and others who wish to limit the spread of these toxic messages is how to do so without compromising journalism’s duty to tell the truth and without undermining free expression. This challenge is not just one that faces journalists, but affects everyone working across the open information landscape.

Confronting the problem of hate speech is easier said than done, not least because there is no clear international definition of what it is. Journalists have to judge themselves what constitutes intense hatred and incitement to violence.

It has always been a tricky question not least because in many parts of the world journalists are recruited as foot-soldiers for nationalism, propaganda and war-mongering. Over the years many have played a deplorable role and in some extreme cases — in Rwanda and Kenya, for example — they have contributed to acts of unspeakable violence and genocide.

While most journalists understand that they have a duty to tell the truth and to report on what is being said and who is saying it, they often fail to balance that responsibility against the need to minimise harm. But how do journalists judge what is acceptable and what is intolerable? How do they embed in their daily work routine a way of assessing what is threatening?

One way developed by the EJN is to help journalists to test the outrageous statements and provocative material that comes their way. Journalists must consider the wider context in which people express themselves and focus not just on what is said, but what is intended. In particular, journalists must question whether speech aims to do harm to others harm, particularly at times of political tension and social unrest.

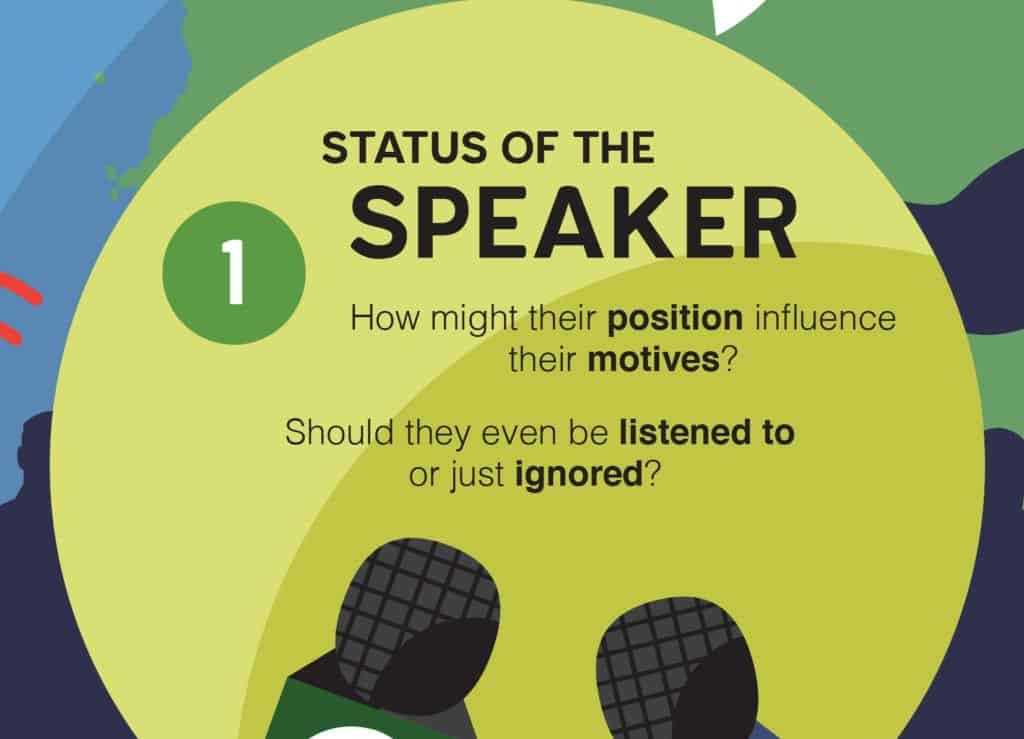

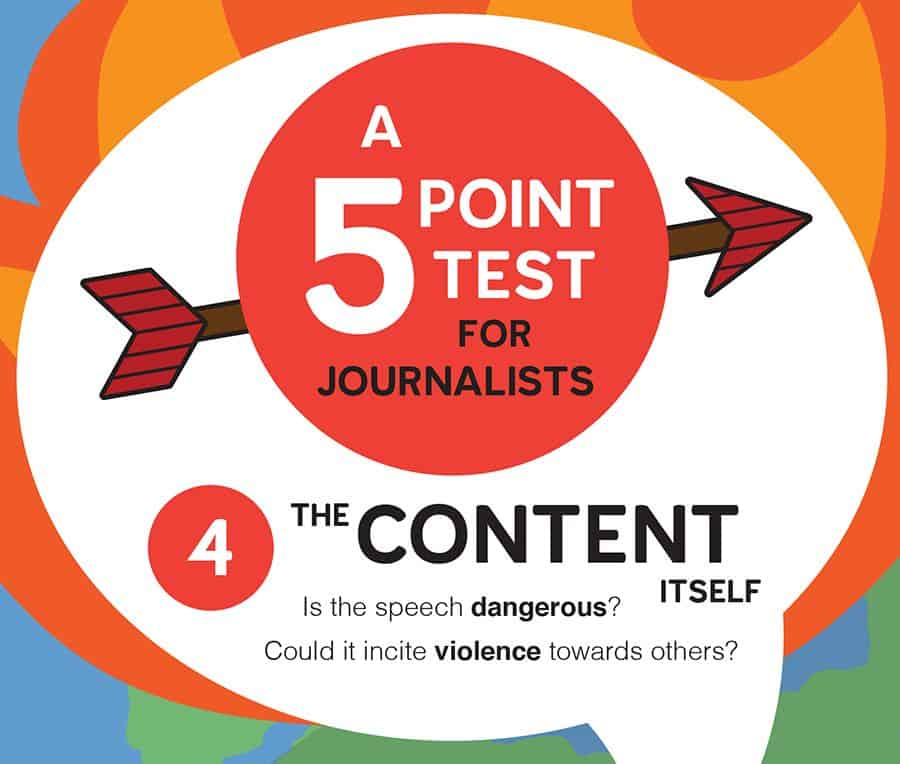

The EJN’s five-point test for hate speech set out here tries to provide journalists (although it could be also useful for others) with a template for testing controversial words and images:

Journalists and editors must understand that just because someone says something outrageous that does not make it news. Journalists have to examine the context in which it is said and the status and reputation of who is saying it.

When people who are not public figures engage in hate-speech, it might be wise to ignore them entirely. A good example is Terry Jones the Christian pastor in Florida who in 2010 was an unknown person with marginal influence even in his rural backwater but who became an overnight global media sensation simply for announcing that he wanted to burn the Koran.

On reflection most ethical journalists might say he was entitled to no publicity for his provocative threats. Journalists have to scrutinise speakers and analyse their words, examine their facts and claims, and judge carefully the intention and impact of their interventions. It is not the job of journalists to adopt counter positions, but claims and facts should be tested, whoever is speaking.

A private conversation in a public place can include the most unspeakable opinions but do relatively little harm and so would not necessarily breach the test of hate-speech. But that changes if the speech is disseminated through mainstream media or the Internet.

Answering the question of the newsworthiness and intention may be helped by considering if there is a pattern of behaviour or if it is a one-time incident. Repetition is a useful indicator of a deliberate strategy to engender hostility towards others.

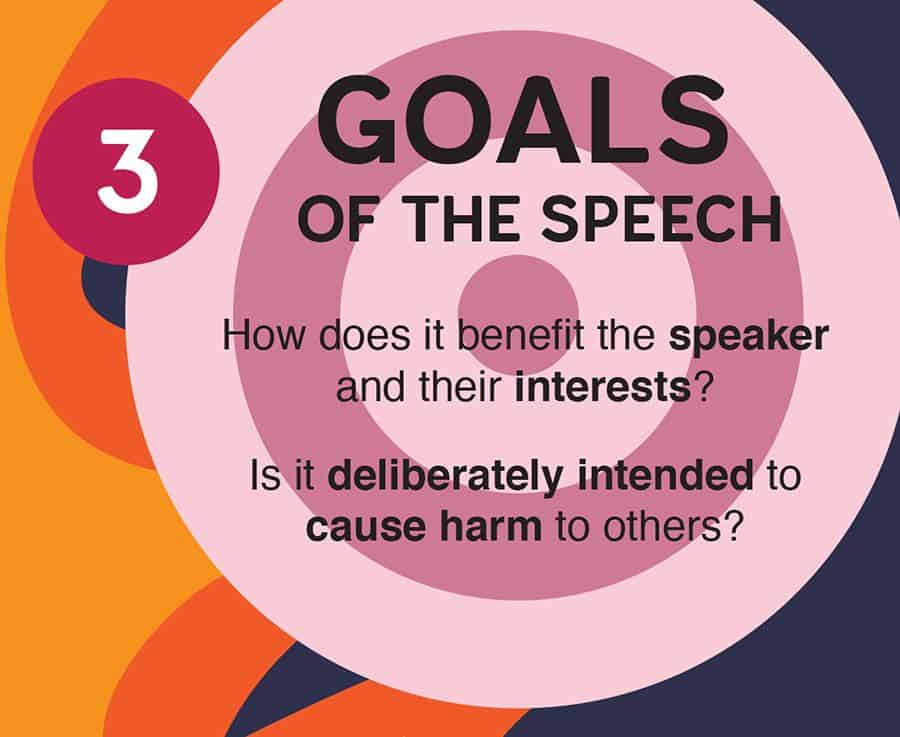

Normally, well-informed editors will quickly identify whether the speech is deliberately intended to promote violence or diminish the human rights of individuals and groups. They should ask if such speech is subject to criminal or other sanctions.

As part of the reporting process, journalists and editors have a special responsibility to place the speech in context – to disclose and question the objectives of the speaker. It is not the journalist’s intention to diminish people with whom they disagree, but reporting should provide context to help people better understand the motives of the speakers. The key questions to ask are: What does it benefit the speaker and the interests that he or she represents? Who are the targeted victims of the speech and what is the potential impact upon them, as individuals and within their community?

Hate speech can be provocative and explicit using well-known forms of abuse, or it may be nuanced and delivered in a subtle manner but with clear messages to the audience. Lots of people have offensive ideas and opinions. That’s not a crime, and it’s not a crime to make these opinions public, but the words and images they use can be devastating if they incite others to violence. Journalists ask themselves: is this speech or expression dangerous? Will it incite violence or promote an intensification of hatred towards others? It might be newsworthy if someone uses speech that could get them into trouble with the police, but journalists have to be wary – they, too, could find themselves facing prosecution for quoting it.

Hate speech is particularly effective and dangerous when times are hard, social tensions are acute and politicians are at war with one another. People who live in uncertain and insecure conditions are often vulnerable to messages that blame others for their troubles. Journalists must, therefore, take into account the public atmosphere at the time the speech is being made.

The heat of an election campaign when political groups are jostling for public attention typically provides the background for inflammatory comment. Journalists have to judge whether the expression is fair, fact-based and reasonable in the circumstances. Where journalists have doubt about directly quoting hateful speech they may report that insulting comments were made without quoting the exact language used.

It is important for journalists to ask themselves: what is the impact of this on the people immediately affected by the speech? Are they able to absorb the speech in conditions of relative security? Is this expression designed or intended to make matters worse or better? Who is affected negatively by the expression?

Read more

Browse the report by clicking on the links below.