Originally published as a chapter of “Conflict reporting in the smartphone era – from budget constraints to information warfare”. Copyright: South East Europe Media Program of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung 2016. Published with permission.

Professionalism and patriotism

Journalists who work in or near a conflict zone see at first-hand the brutal and inhumane consequences of making war. They rarely promote propaganda based upon skewed notions of romantic patriotism or tribal allegiance for long.

Often the media people who shout most loudly and most fearlessly are those who front programmes and pen articles from the safety and comfort of their offices.

In the ethnic and territorial wars fought in the former Yugoslavia, where government-controlled channels like Radio Television Serbia became advocates for the war, and in the recent Ukraine-Russia conflict (Russia Today comes to mind), some media abandoned all pretence at objectivity and became cheerleaders for armed confrontation.

In this charged atmosphere governments strive to recruit everyone – including journalists – to a patriotic and flag-waving cause. It is an atmosphere often filled with hate and emotion.

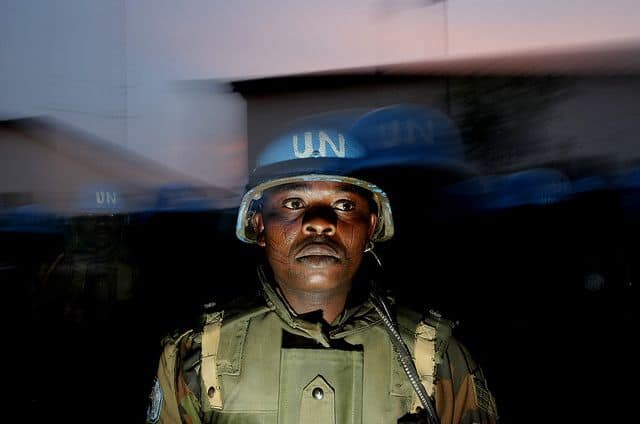

Featured image: UNAMID Peacekeepers Prepare for Night Patrol Exercise (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

But journalism must not be hijacked to provide stereotypes and propaganda. Ethical reporting must portray events and people in an informed context, avoiding the vivid contrasts that governments prefer in their own black and white visions of the conflict.

Reporting from the battlefield may present journalists with a personal conflict of interest. They may become confused when faced by the legitimate urge to defend their community and their culture.

But the role of a journalist is to provide their audience with fact-based information, to show humanity and to strive to tell the truths that need to be heard, even if they offend their own political leaders in the process.

The thoughtful and ethical journalist is a good citizen. They demonstrate their patriotism by doing their job professionally. They know that it is always in the interests of their country and community to strive to tell the truth.

It has always been like this, ever since the first recognisable war correspondents put on their boots to report an earlier war over Crimea in the mid-nineteenth century. But reporting war has never been easy. As former Sunday Times Editor Harold Evans points out, truth gets buried under the rabble-rousing and rubble of war. Only after the conflict, he says, is there time to sift the ashes for truth.

In the updated edition of his award-winning book The First Casualty, which traces a history of media reporting of wars and conflicts, Phillip Knightley warns that it could be getting worse:2

‘The sad truth is that in the new millennium, government propaganda prepares its citizens for war so skilfully that it is quite likely that they do not want the truthful, objective and balanced reporting that good war correspondents once did their best to provide.’

Soon after he wrote these words, the Iraq war in 2003 proved his point, as the American and British communications control system successfully designed an embedding arrangement that gave the media ‘access’ to the action while ensuring that they remained closely supervised by the military.

The presence of 600 embedded journalists allowed the military to maximise the imagery and drama of battlefield conditions while providing minimal insight into the issues. Information was carefully filtered, massaged and drip-fed to journalists. There was a limit to fact and context, lies were part of the package, and setbacks were glossed over. The military carefully planned what range of topics could be discussed with reporters and spun information so that it had the appearance of reality as it appeared to come from troops on the ground.3

The only alternative to this carefully orchestrated vision of the conflict provided by military spin doctors came from up to 2,000 independent or ‘unilateral’ journalists spread out over the territory of Iraq looking for stories that might provide insight into the reality of war. But some of them paid a heavy price.

References

2. Knightley, Phillip (2000) The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Kosovo, Prion Books, p.525.

3. History Channel (2004) War Spin: Correspondent, aired August 21.