Philippines: How media corruption nourishes old systems of bias and control

By Melinda Quintos de Jesus

The Philippines has always had a complicated relationship with its press, going back to the country’s national struggle for liberation from the colonial regime of Spain, when the media seeded the armed revolution with ideals drawn from Europe.

With the proclamation of the Philippine Republic in 1898, the Philippines became the first Asian country to win its freedom from a foreign power. The country was taken over by the United States at the end of the Spanish-American War leading to the establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth. By the time the country claimed full sovereignty in 1946 the press had assumed a strong role, independent and influential.

Filipinos enshrined the protection of press freedom in their written constitutions (1899, 1935). The present Constitution, ratified in 1987 prohibits laws that will abridge “the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press.” Privatisation of the broadcast industry has set it apart. Even with media owners holding political and business interests, the country still boasts of having the “freest” press in Asia.

Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law and ruled the country as a dictator, disrupting media development. But even during the period, an underground press flourished and later came out in protest against the regime. Galvanised by the assassination of opposition leader, Benigno Aquino Jr., a clutch of small publications fused the separate streams of dissident ideas into a national conversation, connecting the different communities to form the People Power uprising in 1986. The press was among the first institutions to operate in the new environment.

The free press operates with the freedom it held during the pre-Marcos era. Private media companies operate for profit. Four national newspapers (Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Philippine Star, Manila Bulletin and Business World) enjoy wide circulation. Radio and television focus heavily on entertainment, but news and political talk shows feature prominently. Broadcast news personalities enjoy huge popular following. Internet and digital platforms for political information and commentary abound.

In this free market, the government may not be the strongest actor in terms of shaping the news agenda. But highly partisan politics make government officials key sources of news. Traditional news conventions and commercial profit control what gets into the news, setting aside the role of the press to inform the public what they need to know as citizens.

And yet, journalism continues to yield some quality, retaining the power to expose corruption. Reports contributed to the firing of corrupt officials, forced government agencies to investigate cases, and even brought about the impeachment of a President (2000) and a Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (2011).

This mixed performance of the press reflects weaknesses and strengths of the larger society as well as its contradictory trends. Political corruption persists, embedded in both the culture and context of business and government. It is not surprising that journalists are also enlisted to serve corrupt ends. Although no licensing system limits the print media, there are laws that restrict reporting of terrorism and rape.

The law still requires radio and television stations to secure a congressional franchise, which could imply a conflict-of-interest transaction. The commissioners of the National Telecommunications Commission are political appointees. The office is not seen as exercising power to supervise the industry, with the level of independence of the US Federal Communications Commission or Ofcom in the UK.

Self-regulatory systems

During the Marcos period, military censorship gave way to voluntary regulatory mechanisms to observe government guidelines for the press. However, a licensing system effectively limited media ownership to the ruling family and Marcos cronies.

There are two print associations. Philippine Press Institute (PPI), a national association of newspaper/publication owners, closed itself down during the Martial Law period to avoid being co-opted by government but reorganised when the regime fell. The Publishers Association of the Philippines (PAPI) was formed to take PPI’s place during the Marcos period. Some news organisations are members of both.

After 1986, the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas (KBP), the national association of broadcasters, continued the system of self-regulation, setting guidelines on its own. Unfortunately, media owners still hold vested interests which may interfere with coverage of these issues.

These press groups set up codes, guidelines and mechanisms to receive complaints: the Press Council for PPI, and the Standards Authority Board for the KBP. But neither has served adequately to address public grievance; they have only a cosmetic effect. Even journalists working on the Press Council have become disenchanted with the process. On its part, the KBP’s sanctions are perceived as weak and meaningless.

One example is case in August 2010, when a disgruntled police officer took a bus hostage with 25 tourists onboard from Hong Kong and Filipino tour staff, declaring them captives in an open site at the Manila’s Quirino Grandstand. He made his demands through the media and held siege for 11 hours, at the end of which eight hostages and the hostage taker were dead. The crisis strained diplomatic relations, with the officials and communities in Hong Kong demanding reparations for the victims and dismissing the formal apologies of the Philippine government.

Government investigations showed how live media coverage contributed seriously to the tension and the resulting tragedy and recommended that charges be filed against the media. The charges were abandoned after media companies marshaled prominent lawyers in their defence. After conducting its own review, the KBP sanctions on erring members were so light as to raise questions about their willingness to genuinely sanction their own.

The business model as conflict of interest

There are presently 1,018 news organisations — print, radio and television — operating in different areas in the country. Journalism operates on different levels, but with exception of church and NGO media, most media operate as commercial enterprises, including news programmes as profit centers.

The commercialisation of the news forces journalists to work for ratings and circulation. This involves a fundamental conflict of interest and clash between profit and the objectives of news as a public service.

Newspapers now run multiple sections, with a large proportion of pages given over to topics such as lifestyle, entertainment, fashion, food and sports, youth and travel. As advertisers and media buyers demand more prime space, newspapers have yielded by creating more of these “soft sections”, thus adding to the number of “front” pages (the first page of each section) and with layouts dominated by ads. News from a traditional journalism agenda is in short supply and there is a fraction of space given over to foreign coverage.

Conflict of interest and employment issues

Journalists and news staff often find themselves caught in a bind where unequal pay and employment conditions lead to unacceptable compromising of ethical standards. While large media companies provide mostly fair working conditions, salary differentials indicate such a huge variance between the pay of star hosts and anchors, producers, reporters and researchers. Greater importance is given to the show-business side of journalism.

At the same time most news organisations in the provinces are small commercial operations producing news weeklies or community based-radio/TV stations who would operate at a loss if they hired and paid for trained editorial staff or broadcasters. In the regions basic corporate obligations, such as insurance and other benefits to employees are ignored. It is a hard life, but this fact has not deterred the numbers of young people and others who wish to work as reporters.

Provincial weeklies are assured some form of income through the printing of judicial announcements issued by the government, decreed during the period of Martial Law as a way to gain support of the provincial press. These judicial notices or any other official announcements are not always distributed fairly, however, and may often be made in exchange for favorable coverage of those concerned.

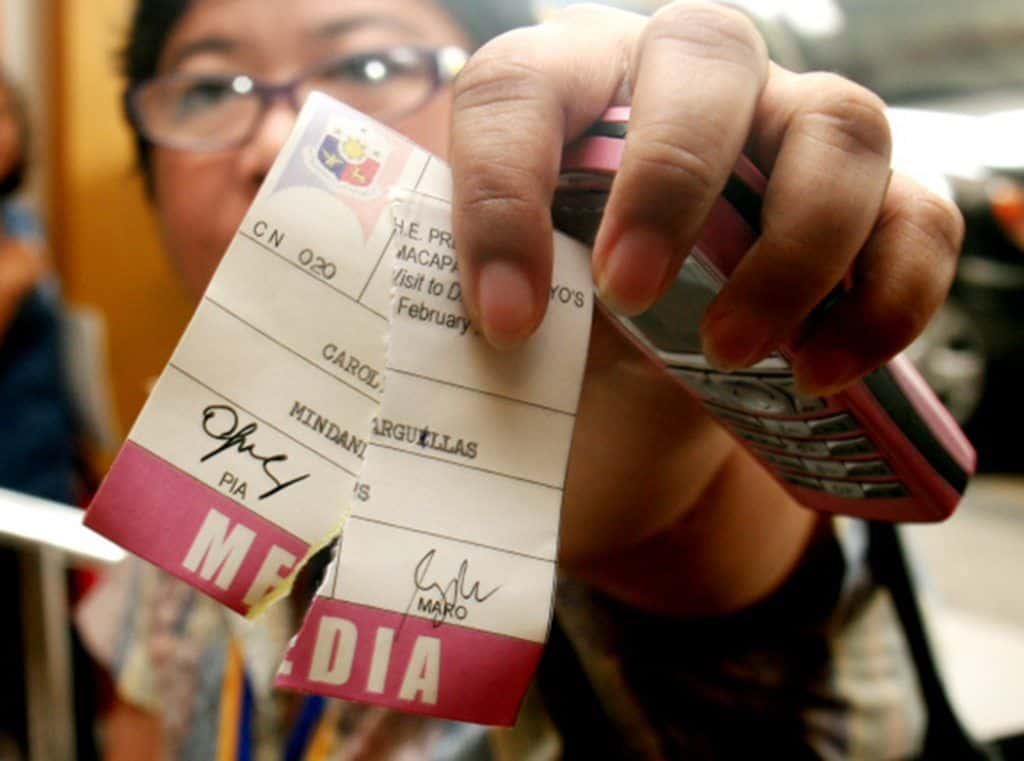

“Oscar Sañez” by Mark Hillary (https:// ic.kr/p/5Yxoix) is licensed under CC BY 2.0

PPI executive director Ariel Sebellino says local government units can influence media coverage with government advertising in the provinces through “mostly judicial notices.” He adds: “there are government ads that intend ‘to bring them closer’ to local media or newspapers. And this is self-serving knowing that they want tamer coverage on them. Short of saying, (it is) PR (public relations).”

The quality of community press varies widely. There are dedicated journalists reporting on corruption in local governments, police or business operations, and they are often endangered for doing so.

When small media owners do not pay regular compensation or benefits, reporters themselves are asked to solicit advertisements from local merchants or government and are given commissions or shares of earnings from these ads. These practices give rise to conflict of interest issues and violate ethical standards. Sebellino said: “Marketing people getting commission for paid advertisements is a standard. But there lies the problem when a self-proclaimed journalist or reporter also acts a ‘solicitor’ or marketer.”

The shadow of paid-for journalism

During the 1970s, a call for journalism in aid of development provoked heated discussions. Its legitimate progressive aspects were co-opted by governments wanting to control the press. The practice saw the wholesale and institutional re-purposing of journalism as a vehicle for state propaganda.

This also encouraged and institutionalised the practice of cash incentives or gifts given to journalists to secure favorable coverage. The conflict of interest is obvious: a journalist who takes bribes is reporting for his personal gain. A reporter then can slant the story to favour a subject who has paid or promised payment and shares the reward with other editors.

The practice cannot be excused because of low salaries: even those who are well paid succumb to bribery. The overall lack of transparency is sinister. During the Marcos years the press openly favoured the regime. Given today’s supposedly free press system and the claim for press autonomy, “paid-for news” and political bias can be passed off and appear as legitimate stories.

There is now a rich taxonomy of media bribery and those described below are among the more colorful:

- AC-DC (Attack-Collect-Defend-Collect): A kind of journalism where the reporter attacks a person in order to collect money from that person’s rival or enemy. The same journalist then defends the person originally attacked, also for a fee.

- ATM journalism: Refers to a practice in which reporters receive discreet and regular payoffs through their ATM accounts. News sources simply deposit cash into these accounts instead of handing the money over to journalists through envelopes.

- Blood money: A payoff before publication to ensure that a story or a critical article is killed, or else slanted to favor whoever is paying.

- Envelopmental journalism: A take on “developmental journalism,” a concept which became popular during the martial law period, when the Marcos regime appropriated the term to discourage criticism. The generic term refers to various forms of corruption.

- Intelligentsia: A play on “intelligence” as used by police and other security forces; this is the share of journalists on the police beat of bribe or protection money given to police.

The advertorial

The line between editorial and advertising content blurs easily on the pages of newspapers, where the content of reports may sometimes legitimately provide consumer information about new products in the market. However, the most blatant demonstration of a conflict of interest occurs when the advertising contract includes non-advertising content. The “advertorial” is presented as a report, but it is nothing but re-packaged advertising material, produced by ad companies.

The advertorial has also made its way into the community-based press as described by Sebellino: “Advertisers now want their traditional advertisements to be accompanied by articles and some of these are disguised as news. So that newspapers package these as marketing strategy to augment revenues.”

Broadcasting organisations have depended on the practice of “blocktimers” as a revenue stream. The KBP Broadcast Code defines the term as when “natural or juridical persons… [buy] or contracts for or is given broadcast air time.”

It applies to entertainment as well as public affairs broadcasts. The radio or television station, sells the time segment (programmes can run from one-hour or more) to a “blocktimer” who can then produce a programme independently. The station does not pay for expenses. It assures the station owner revenue for the media segment, without any marketing effort.

The blocktiming company, group or individual is free to get advertisers or not. The practice is used for political campaigns or for other forms of advocacy and it is open to any association, charities, public service NGOs, church or religious group, a government agency, political party or politician.

KBP’s power is limited to member stations. It is unable to monitor all the blocktime programmes. Media companies which are not KBP members operate with little accountability for its operations. In general the practice of blocktiming is practically unregulated.

KBP executive director Rey Hulog said the association is updating its list of blocktimers. In 2007 to 2010, KBP local chapters reported around 354 blocktimers — “at least one station with a blocktimer on the air in every major city or municipality.” The Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) notes that these were election years, but even so, the practice is common, with or without elections. It is increasingly seen as standard practice for the broadcast industry.

Full disclosure helps mitigate the conflict of interest. The public should know the real identities of those involved in the blocktime transactions, the source of the information and who benefits from this exposure. When a well-known professional broadcaster agrees to host a programme on behalf of an unidentified blocktimer, he or she may lend credibility to a propaganda campaign. Such programmes are launched in advance of an election, presenting a broadcaster as an independent commentator on false pretext.

The KBP and PPI issued a review of blocktiming and other forms of corruption (In Honor of the News: Media Reexamination of the News in a Democracy). But the practice continues and is virtually unsupervised.

Transactions for election coverage

A publication of the PCIJ, News for Sale (2004), documents the wholesale transaction between political candidates and media broadcast networks to assure coverage of political candidates, arrangements apart from the placement of political ads. These commit airtime through interviews and appearances in shows and programmes of network affiliates all over the country.

“Given the power that television wields, media strategists in 2004 exerted greater effort to capture the TV audience through advertising, aggressive public relations with broadcasters, and all sorts of means—legitimate and otherwise—to sway television coverage in their favor.”

With electoral laws limiting the candidate’s spending on television advertising, such airtime expands the exposure for political candidates. The practice diminishes the role of independent journalists in determining the kind of political information the public receives during a campaign. Media marketing has taken over the function.

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism reported: “In the 2004 elections, as in the 1998 presidential and 2001 senatorial races, radio networks struck million-peso deals with campaign managers that allowed candidates and parties to circumvent legal limits on advertising and media exposure. These deals involved ‘commercial packages’ offered to candidates and included a guaranteed number of commercials, press releases, daily interviews, and rally coverage aired on the networks.”

Journalist sources told CMFR that such arrangements were still very much in operation during the 2010 and 2013 elections.

Some journalists are retained by political groups to produce campaign reports, without taking leave of their jobs. Political campaigns also take care of the needs of assigned reporters, including meals and other expenses.

Another issue is product endorsement by news personalities which has been prohibited by one major television network, ABS-CBN 2. But it is allowed in a rival company, GMA-7. It is not always clear whether this system provides them with extra compensation from the advertising revenue. The practice has not been questioned by the KBP.

Lack of transparency: Online news and commercials

Exchange deals, merchandise and other business services, are not all reported and the audience can be oblivious to the advertising content in these so-called news features. Exchange deals are used for employees as well as for guest entertainers or commentators who are not paid anything for their time.

These practices have also found their way online. Puff pieces on companies and their services appear as regular articles but may have been produced on the basis of an exchange.

There has been no effort to establish rules about how news services online should clarify the division between advertising and news. The dynamic character of web and social networking sites further blurs the distinction between news and advertising and the lines separating the two. Advertorial features can be found in the same space (home pages and social media timelines) as the news and other independently-produced editorial content.

“Likes”, “retweets”, “hits” and “visits” are the Internet’s currency. People who can provide these are paid for the service. In an environment where disinformation and misinformation abound, “influencers” can dictate agenda and content, and act as a media “point man” and/or “shepherds”.

The search for solutions

The range of challenges and opportunities for corruption and bad practice compels the media to improve enforcement of self-regulation at industry level. However, a mix of self-interest and scant means for internal monitoring suggest that media owners are wary of exerting their power either because they do not care or are unable to enforce discipline.

“Useless” by Keith Bacongco (https:// ic.kr/p/4uT69b) is licensed under CC BY 2.0

PPI and KBP know that the Press Council and the Standards Authority are passive mechanisms, activated only by public complaints. According to Sebellino and Hulog, the two associations are working on a more “efficient” way of monitoring these common practices.

Although the general public is the most important stakeholder in the fight against conflicts of interest in the press, people are often passive consumers of news. In general, the public remains uninformed about how easily and extensively the news can be manipulated. Only a small segment of the audience would be able to detect a media spin, and even fewer would know enough about an issue to check inaccuracies in a report. Even if they are aware, they do not bother to complain or express their criticism.

Press ombudsman?

The creation of a national independent Press Ombudsman has never really been discussed. Ideally, this should be a mix of funding that includes contributions from the media industry as well as a government subsidy. The latter however is usually regarded as a barrier to autonomy and independence.

Yet the country’s experience with independent agencies, such as the Constitutional commissions (the Ombudsman, Civil Service Commission and the Commission on Audit) could help assess the acceptance of such an agency.

Media literacy training for the public

The lack of understanding about how journalism operates and the dangers of misinformation suggest that people must learn to understand the media and the role of the press. They must appreciate why the press is protected. But there must also be appreciation for the need for media accountability.

Media literacy training can be undertaken in schools. More important, there should be training for citizens, including public officials but particularly for the public, so an audience is empowered to evaluate and criticise media practice when necessary.

Main image: “Manila – 7th day: Trip to Tagaytay” by Roberto Verzo (https:// ic.kr/p/8q8tkJ) is licensed under CC BY 2.0