By Sven Egil Omdal

The editor of the newspaper Fremover (Forward) in Narvik didn’t put up much of a defence. In an article, based on another newspaper’s reporting, Fremover had claimed that the confidential security plans for the local airport, a joint military and civil installation, had been freely accessible on the servers of the local authorities. When this claim was refuted, the paper had no documentation to the contrary.

The Norwegian Press Complaints Commission (Pressens faglige utvalg, PFU) needed less than ten minutes to reach a unanimous decision that Fremover was in breach of paragraph 3.2 of the code of conduct, the one that states that you should get your facts right.

For those interested in the case, the video from the discussion is still available at the site of the trade publication Journalisten. The complaint was one of a record 212 cases brought before the commission in the first half of 2014, dwarfing the former record of 185 from the first half of 2012.

It was also one where the discussion among the seven members of the commission; two editors, two journalists and three representatives of the public, was being streamed by Journalisten. As part of the commission’s transparency programme, three cases from each meeting are streamed live. The meetings are open to the public, but are held in a conference room with few spare seats.

The significant increase in the number of complaints over the last decade has been used to argue that the standards of Norwegian journalism are deteriorating, and that sloppy reporting and disregard for the privacy of public figures are on the rise.

The statistics show, however, that the percentage of cases where the media is being found in breach of the code of ethics, has been stable, or is diminishing. An increasing number of complaints, almost half the total number, are being settled by the secretariat as “obviously not in breach”. This may indicate that the growing number of complaints, rather than proving that Norwegian journalists are behaving less ethically, is an indication of the increased awareness and acceptance of the self-regulatory system.

The journalist in Fremover who wrote the disputed article (or cut/pasted, as the complainants claimed) was not a party in the case. As is the rule, the editor-in-chief handled the complaint after consulting with those involved in writing and editing the story. The ruling of the PFU was directed at the paper, not at the journalist or the editor. But the journalist is not free from personal responsibility. According to the brand new corporate “guidelines for ethics and social responsibility” of Amedia, the group who owns Fremover, all employees are “obliged to study and follow” the ethical guidelines.

Amedia is the second largest of the three corporations that dominate the Norwegian newspaper market, owning completely or partially, 78 newspapers. Stig Finslo, vice president for publishing issues, says in an interview that the corporate guidelines are partially based on legal requirements, but they are also an attempt to protect freedom of speech and industry rules like the ethical code (“Vær Varsom-plakaten”) and the “Rights and duties of the editor”, a voluntary agreement between the Norwegian Editors Association and the publishers association (the principles in this agreement has since 2009 been legally protected by the Editorial Freedom Act).

Amedia is not alone in establishing corporate rules that are both more comprehensive and in certain aspects stricter than the national code. A majority of the large news organisations have similar house rules. But Amedia go further than the competitors, regulating both the spare time of journalists (engagement in voluntary associations “must not infringe on the independence and integrity of members of the editorial staff”), their activity in social media (“must not harm your own or the company’s reputation”) and sexual behavior (“anyone on assignment for, and representing, the corporation must abstain from buying sexual favors”.)

The fact that corporate rules both exceeds and strengthen the national ethical code should not be interpreted as discontent with the self-regulatory system. The work of the PFU is arguably more widely accepted today than it has ever been. It seems that turning the institutional framework into a one-stop system covering all media, including broadcasting and online, has made the ethical regulation of Norwegian journalism at the same time both more visible and more legitimate.

KIEV, UKRAINE – MAY 21, 2014: Woman looking on social media applications on modern white Apple iPad Air, which is designed and developed by Apple inc. and was released on November 1, 2013.

The Press Association (Norsk Presseforbund, NP), an umbrella organisation comprising the editors association, the Norwegian union of journalists, the various publisher associations and all broadcasting institutions, decided in 1994 that the PFU should handle complaints against all media, including those not belonging to any of its member organisations.

At the same time, a Government White Paper discussed the need for a publicly appointed media ombudsman. The government reached the conclusion that the voluntary system worked so well that there was no need for a parallel structure. Four years later, in 1998, the jurisdiction of the PFU was enlarged further when the Parliament decided to abolish the mandatory Broadcasting Complaints Commission (Klagenemnda for kringkasting), thus leaving Norway in the unique position of having no mandatory regulatory body for any part of the media.

The reason for the abolishment of Klagenemnda, given by the then Minister of Culture, Åse Kleveland (a former PFU member, representing the public), was the high legitimacy, effectiveness and visibility of the PFU-system. She stated, however, as a prerequisite that all broadcasting organisations should respect and follow the rules and regulations of the PFU, threatening legislation if there was less than 100 percent compliance with the self-regulatory system.

One particular problem had to be solved before the transfer of authority from the Klagenemnda to the PFU could be concluded. Article 23 of the EU directive on television states that “member states shall adopt the measures needed to establish the right of reply or the equivalent remedies and shall determine the procedure to be followed for the exercise thereof”. The Norwegian government was of the opinion that as long as the code of ethics included regulations concerning the right of reply, the requirements of the directive were met. But to be on the safe side, the parliament adopted a new paragraph in the Broadcasting Act guaranteeing the right of correction of factual errors.

Online media were included in the jurisdiction of the PFU as early as 1996, less than a year after the appearance of the first net editions of Norwegian newspapers. In an attempt to limit the rapidly growing workload of the commission and the secretariat, it was decided that only complaints against publications or sites with a predominant journalistic profile and a responsible editor would be considered. On the other hand, the commission also accepts complaints against institutions, organisations, companies or individuals accused of obstructing the work of journalists.

Researching this paper I asked the editors of three of the largest Norwegian newspapers how they handle PFU complaints, and to what extent they try to enhance the ethical competence of the editorial staff.

All the papers have in-house codes of conduct that are both more detailed and stricter than the national code. Bergens Tidende (BT) publishes both their code of corporate responsibility and their editorial ethics code in the web edition of the newspaper. Editor-in-chief Gard Steiro explains that he and the managing editor shares the responsibility for handling complaints. All decisions by the PFU concerning BT, positive as well as negative, are being distributed to the whole newsroom and discussed at meetings in each department. In addition, ethical issues are frequent topics at a weekly meeting for all the journalists and editors.

Torry Pedersen, CEO and Editor in chief of VG, which is by far the largest online news organisation, in addition to having the second largest print circulation, says that they approach all complaints in a systematic and well established manner. After being reviewed by him, the complaint is sent to the editor responsible for ethical and legal matters. All personnel involved in the disputed article; reporters, subeditors, photographers and editors are required to describe in writing their involvement with the article, including any decisions they took. Based on these reports the editor for ethics writes a draft reply to the PFU, which is then sent back and forth between him and the editor in chief until the latter is satisfied.

All complaints deemed relevant are mentioned or discussed in the editor’s daily briefing with the whole editorial staff. All PFU decisions involving VG, regardless of the outcome, are analysed in detail by the editor at one of these meeting, followed by a written version of the analysis. In addition to that, all summer interns go through a two-day introduction course where the company’s policy on press ethics is presented in detail, Pedersen says.

Before being appointed editor in chief Lars Helle used to be “editor for ethics” in Dagbladet, Oslo. The fact that this brazen tabloid established such a position drew considerable interest not least from public figures critical of the paper’s coverage. Helle (who since 2012 is the editor in chief of Stavanger Aftenblad) says that it was important to communicate, especially to the staff, that the existence of an editor for ethics did not imply that the editor in chief had abdicated this field. Helle was in charge of all in-house training in ethics, running a series of workshops and seminars, handled all complaints, represented the paper in public discussions on controversial editorial decisions and also represented the paper in all legal conflicts (he has a degree in law).

BT was the first Norwegian media institution to introduce the concept of press ombudsman, when Terje Angelshaug, a former news editor of the paper, was appointed in 2004. When he left the paper in 2011, the position was discontinued. It proved difficult to find someone with the right balance of authority, competence and legitimacy both internally and towards the public.

In 2010 the Swedish media research institute Sim(o) published a study of what they called “The Norwegian Model”. In the preface Torbjörn von Krogh writes that although the Norwegian system is based on a different legal and organisational framework, there is a lot to be learned from a model that for 20 years has worked as a comprehensive system for self-regulation.

The PFU traces its history back to 1928, and is the third oldest in Europe after Sweden (1916) and Finland (1927). The ethical code, first adopted in 1936, has since been revised 11 times, the last revision being effective as of July 1, 2013. It is safe to say that several of the revisions have been made to avoid legislation. In a study of European laws on self-regulation in the media sector, presented to the Saarbrücken conference, organised by Germany under their EU presidency in 1999, Dr. Jörg Ukrow at the Institute for European Media Law wrote that self-regulation would be beneficiary in “avoiding sovereign intervention in areas which are sensitive in terms of basic rights. State intervention in press, film and broadcasting freedom is often claimed to be justified on the grounds that the state has to protect the public from abuses of the mass media. If the profession regulates its own affairs, the state has no reason or excuse to intervene”.

It is widely accepted that the strength of the Norwegian system to a very large extent is based upon the ability and willingness of the publishers, editors and journalists to agree upon both the code and the system managing the code. This consensus has survived seismic shifts in the media landscape; the transformation from a largely political press to a newspaper scene almost totally dominated by three corporations, the expansion to cover all media, and lately the almost exponential growth in online publications and the shift to a 24/7 publication cycle.

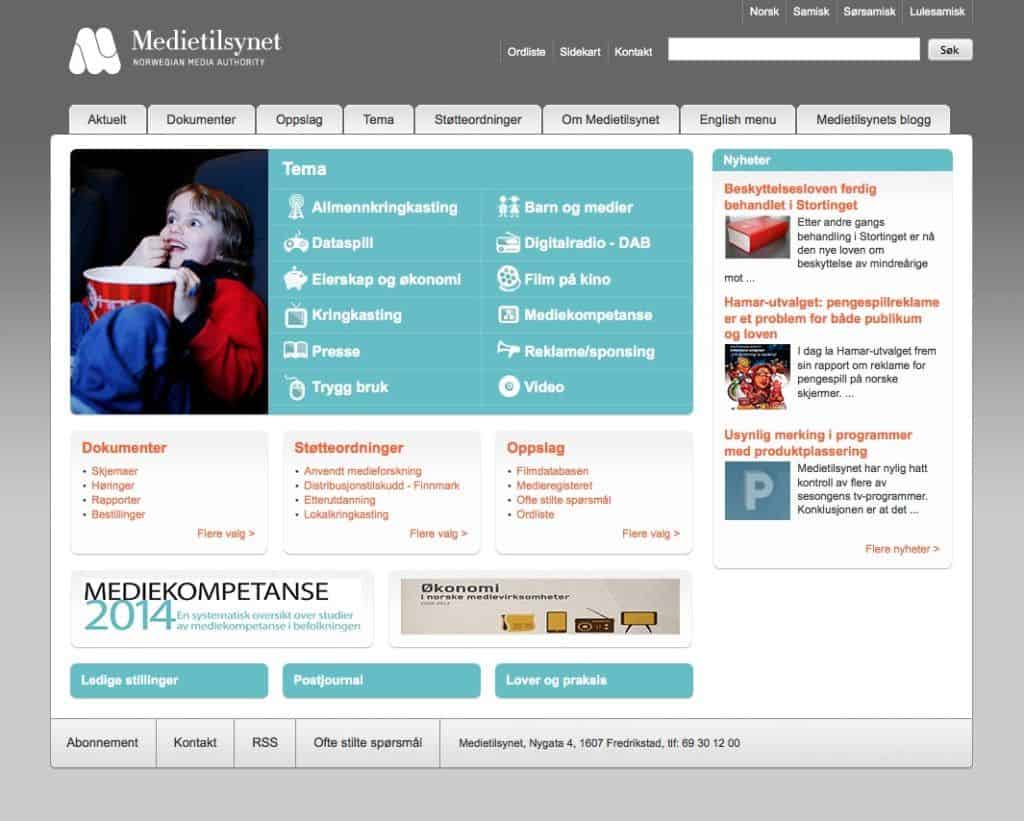

The public perception of the system has been strengthened by a program of transparency. Ownership transparency is regulated by law, and controlled by the Norwegian Media Authority, who publish an annual report listing the owners of all Norwegian media. The press association has opened up the regulatory process by holding PFU meetings around the country, inviting local journalists and members of the public to act as shadow commissions, discussing the same cases, with the same input from the secretariat. In addition, as mentioned above, three cases from each meeting of the PFU are being streamed live, and kept as video files on the web site of Journalisten, a trade journal owned by the Norwegian Journalists Union.

Even in the absence of political pressure to reintroduce mandatory regulation of the media, the question of representation on the PFU frequently arises. As a result of one of these discussions, the Norwegian Journalists Union voluntarily gave one of their three seats to a representative of the public, bringing the composition of the complaints commission to its present division between editors (2), journalists (2) and representatives of the public at large (3). The chair and the vice-chair of the commission are always an editor and a journalist on a rotation basis.

All seven members are appointed by the board of the Press Association (Norsk Presseforbund, NP). The Secretary General of the NP nominates the representatives for the public, while the journalists union and the editors association (Norsk Redaktørforening, NR) nominate the representatives of the journalists and editors respectively.

There have been repeated but unsuccessful attempts to find an independent external institution that could nominate the representatives for the public, and the present system regularly draws criticism. Among the latest appointments are several members with personal experience of being negatively portrayed in the media, apparently in an attempt to bring the hardest criticism of media behavior into the deliberations of the commission.

The Secretary General of the NP also has a right to initiate investigations in cases where no complaint has been lodged. This right is normally used only a few times each year, and the complaints from such investigation have always been upheld by the PFU.

The Secretary General also initiates infrequent “declarations of principle” by the commission. One example of such a declaration is a 15-point guideline on the right to reply, adopted by PFU in early 2011.

Breaching the two paragraphs in the ethical code regulating the right to reply (simultaneous reply in para. 4.14 and post-publication reply in 4.15) has been characterised as “the original sin” of Norwegian media. The annual statistics almost without exception show 4.14 as the most transgressed upon of all the paragraphs in the code.

The guidelines adopted by the PFU in 2011, was based on preliminary work and precedents in the commission. The guidelines stress that persons accused of serious misconduct must be given a genuine opportunity to respond, that the editorship must endeavor to make contact with the person, who should be informed – in a straightforward manner – of the specific accusations, and be given a reasonable time to respond.

When the guidelines were presented, the then Secretary General of NP, Per Edgar Kokkvold, stated that they were issued for the benefit of the editors and journalists as well as the public, and that there would be an end to critical 4.14 adjudications if editors carefully read them.

For whatever reason, whether lack of time to read the guidelines; insufficient respect for the code of ethics; or weak systems of control in the newsrooms, the right to simultaneous reply to serious accusations continued to be the weak spot of Norwegian press ethics.

In 2013 the editors association established the “4.14 squadron” in order to approach the problem more forcefully. It is probably too early to draw any conclusions, but during the first half of 2014 the number of cases where the media was found in breach of 4.14, was halved, compared to 2013, reinforcing the arguments of those who think that the awareness of the code among the practitioners leaves a lot to be desired.

An important prerequisite for the independence of the system is the fact that it is fully financed by the participants. All member organisations and broadcast media belonging to the press association, NP, pay a fee which covers the associations’ work with press freedom, media legislation, as well as the work of its committees, of which PFU is by far the most active and important.

It could be argued that the membership fee of the state-owned Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (Norsk Rikskringkasting, NRK) indirectly constitutes an element of public financing. NRK is organised as a foundation with an independent board of directors appointed by the government, and is financed by a license paid by all who own a television set.

The sanctions are few, but well respected. Any publication found in breach has to publish, as soon as possible, the PFU finding in a prominent place, including the PFU logo and under a non-contentious headline. When a broadcaster is found in breach, a short version of the finding is prepared by the secretariat to be broadcast in the same time slot as the offending publication.

In the case that the commission finds against a publication which is not a member of the Press Association and who refuses to comply with the rules, the NP will pay for ads making the finding known, choosing the publications most likely to reach the audience of the offending publication. These cases are rare, as almost every publication with a predominant journalistic content and a responsible editor, belong to one of the member organisations of the NP.

The idea of an administrative fee payable by those found in breach, comparable to the Swedish system, has been floated several times, but has received little support from the industry. The main argument against a fee is that it would be regarded as a fine, making the self-regulatory system more like a court of justice, something that has been avoided since the system’s inception.

A number of studies since 1996 have explored the perception among Norwegian journalists with regard to the PFU and the standard of journalistic ethics in the country. In a submission to the Independent Media Inquiry in Australia in 2011, Dr. Johan Lidberg, senior lecturer at School of Journalism at Monash University writes that “the data shows a strong consensus that the new regime (encompassing all media in a one stop-system) has lifted journalistic and publication standards in Norway, and that the respect for PFU’s work is great indeed”.

Lidberg quotes a 2001 study by Svein Brurås, assistant professor at Volda University College, on how journalists regard the self-regulatory system. His conclusion was that they “spontaneously express that the PFU is doing a good job and that their rulings are seen as fair … it can be concluded (based on the interviews) that the journalists hold the PFU in great respect and it is viewed as a body with authority and integrity”.

A recent study, presented as a bachelor thesis by Monica Christophersen, student at the University of Stavanger, strengthens the impression that the work of the PFU has a strong influence on ethical standard in newsrooms. Her survey of 66 newspapers and broadcasting institutions showed that 82 percent of those who were found in breach during the last 10 years initiated changes in newsroom routines as a consequence. Of these changes, 31 percent were of a substantial nature.

Christophersen states that “most newsrooms introduced small and simple measures. For the majority this was sufficient (to avoid being found in breach once more). For larger newsrooms and other newsrooms with repeated breaches, there has been a need for more and heavier measures. Regardless of whether the changes were large or small, this indicates that they are concerned about the findings of the PFU, trying their best to avoid a repetition”.

An example of measures that might be introduced was seen in the 2013 case of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation when they reported a story in the main nightly news about an imprisoned Roma woman, claiming that she was jailed for living in accordance with the traditions of her people. The report omitted the facts, well known to the reporter and his editor, that the woman was sentenced for trafficking and aiding in the rape of her own 11 year old daughter.

Even though NRK published a retraction and apologised, PFU found that the report was in “severe breach”, and added for good measure that it was a case of falsification of history.

In the aftermath, humiliated NRK management issued several written reprimands, organised mandatory refresher courses in ethics for the staff and introduced a system where a high ranking editor would be present in the newsroom every night until the conclusion of the main news broadcast.

The perception that press ethics is taken seriously, is supported by Lars Helle, former editor for ethics at Dagbladet. When asked how this job was perceived in the newsroom, he said: “It was received with immediate respect. In cases small and large, I was consulted far more often, day and night, than both the editor in chief and the news editor. Due to this respect, the position became much more important than I had expected. The same was true for the external reception, probably because the title was a rarity in Norway”.

A growing number of newspapers publish an annual editorial report, parallel to the financial report prepared by the CEO. In this report, published in the paper and online, the editor discusses the successes and shortcomings of the previous year, often pointing out how many – or rather how few – times the paper has had a negative finding in the PFU. Readers are then invited to discuss the report and decide if they agree with the picture painted by the editor.

The 2013 Annual Editorial Report from VG is divided into “things we are proud of”; investigative project, innovations, prizes, international coverage, and “things we are not proud of”. In this latter section, the editor in chief, Torry Pedersen, lists the numbers of corrections, regretting some cases where they had mistreated people or invaded the privacy, lamenting the low number of female sources, admitting that sports coverage were given to much space and resources, and revealing the average annual salary of the journalists (NOK 711,059, approximately Ä86,000) and the editors (NOK 1.2 mill, approximately Ä145,000).

But for those wondering if VG’s well-established system for handling complaints, as described above, actually works, the most relevant information is the fact that VG, an aggressive tabloid with a daily circulation of 164,000 and a total daily readership on all platforms of 2.3 million in a population of 5 million, was not held in breach of the ethical code even once through the whole of 2013, and that the same was true for 2012 and 2011. As Torry Pedersen says: The system guarantees quality.

Main photo: “Reading the newspaper” by James Cridland (https:// ic. kr/p/NpdZw) is licensed under CC BY 2.0