This is a Chapter of the Study “How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration?” carried out and prepared by the Ethical Journalism Network and commissioned in the framework of EUROMED Migration IV – a project, financed by the European Union and implemented by ICMPD. © European Union, 2017.

MALTA

The Challenge of Normalising the Media’s Migrant Crisis Machine

Mark Micallef

On the surface, Malta has a vibrant media landscape. The Mediterranean archipelago currently hosts three national television stations, and a small commercial outlet, more than ten radio stations, 12 newspapers – four of which are dailies – and about eight online news portals. This is despite the fact that in terms of population, Malta is equivalent in size to Manchester. This disproportionate diversity is not the result of the island’s extraordinary productivity but rather has to do with the fact that the local industry does not obey market principles and remains dominated by the country’s political institutions; the main political blocks, the incumbent Labour Party (Social Democratic) and the Nationalist Party (Christian Democrat), the Catholic Church, and Malta’s largest union, the General Workers Union (GWU).

This dynamic effectively stifles prospects for privately-owned media, especially in the broadcasting sector, and consolidates the dominance of these institutions over the public sphere, exacerbating the challenges of operating in a micro-economy. On top of this artificial race for market share, Maltese newsrooms have to meet the particular exigencies of covering a city state. News outlets perform a hybrid function, dealing with international, national and hyper-local news simultaneously.

A day’s typical news agenda may have a list of political, economic, court and crime stories, something between what you might see in a European national newspaper (but not quite at the level of a regional outfit); a focus on a pressing development in neighbouring North Africa, and a raging dispute over garbage collection arrangements in a village of 1,000 people.

This context is vital to understanding news coverage of migration in Malta. The fragmentation of the market means all editorial departments are under-resourced, most of them severely. At the time of writing, the country’s largest newsrooms would not have more than four to five writers on any given shift. As a result, hardly any media is really able to meet the news demands outlined above, let alone invest in the immersive journalism needed for reporting on large scale, complex phenomena such as mass irregular migration.

Mario Micallef, News Coordinator at the national broadcaster Television Malta, also believes Maltese journalism is facing an acute cyclical human resources problem that makes matters worse. “If we issue a call for applications, there will be no shortage of CVs but when you go through with the interviewing process you end up asking yourself if any of the candidates really have what it takes. This limits your options severely when it comes to the day-to-day coverage of something delicate like migration.”

In spite of this challenging and uneven landscape, migration proved to be a nexus issue that focused resources and empowered parts of the press, individual journalists and columnists, and civil society, to assert their independence from institutions and demand more accountability from the state.

This does not mean that the reporting has been easy, far from it. The importance of this spontaneous, civic-minded dynamic cannot be overstated in analysing the Maltese media coverage of migration. The editorial line of virtually all news outlets rows against the tide of the xenophobic sentiments of large swathes of the Maltese population. As argued by leading Maltese media researcher Carmen Sammut, a purely commercial industry would not be able to sustain that situation in a small market like Malta.

Social researcher and co-founder of the NGO Integra Foundation, Maria Pisani argues that the most obvious difference between the media in Malta and elsewhere, is the complete lack of tabloid press. “Malta is lucky. There is nothing like what we see in the British tabloid press, for instance, and that is a great advantage. I would say the Maltese press has been responsive when journalists’ attention was drawn to issues with their work.”

Shock and awe: the first years of boat migration

Most of Europe woke up to the ‘crisis’ in 2015 with a surge of Syrian asylum seekers fleeing war and life with no prospects. Southern European states were acquainted with the phenomenon well before 2015, but even then the initial reaction was one of unprepared shock.

On 2 November 2001, one of the very first ‘boatloads’ of sub-Saharan African migrants landed in Malta , just weeks after the country ratified the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, broadening the islands’ commitment to offer asylum to non-Europeans. Around 57 men, the majority from Sudan, ran aground at a tourist hotspot, appropriately called Paradise bay. Both events received little attention despite setting the tone for what would later become the country’s defining crisis.

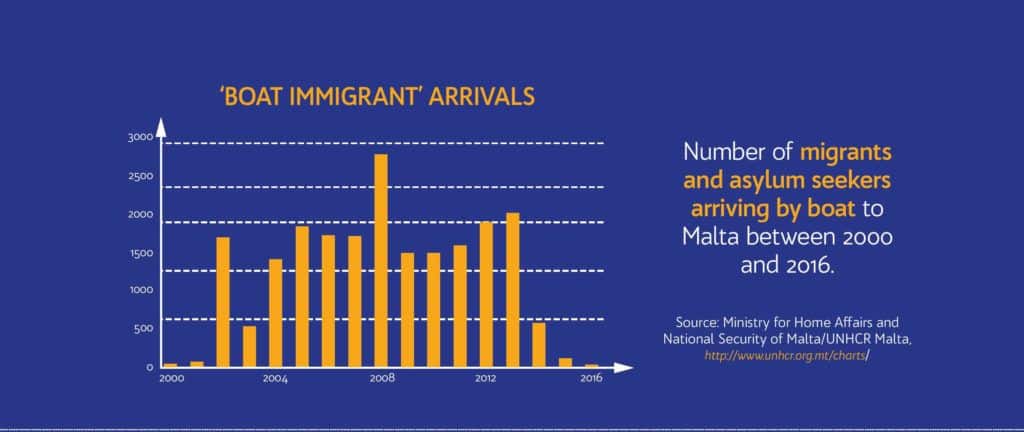

In 2002 arrivals shot up to 1,686. The public discourse was instantly dominated by words like “crisis”, “influx” and “siege”. The following year, the debate took a backseat as the country debated EU membership and arrivals dropped substantially. However, it returned with a vengeance in 2004 when almost 1,400 people arrived. The numbers kept climbing until 2008 when an all-time record of 2,775 arrivals was recorded. A year later Italy brokered a controversial deal with Libya to push back asylum seekers and arrivals plummeted until the revolution in 2011.

During these early years, most journalists’ initial reaction was to replicate the sentiment of shock and sense of crisis. Virtually all of the reportage, with some exceptions, was preoccupied with the limit of Malta’s size and resources. The use of terminology was uninformed, clumsy, in many instances insensitive, and occasionally outright xenophobic. “Illegal immigration” and “illegal immigrant” were used as blanket terms even by sympathetic outlets. Maltese-language newspapers tended to use the pejorative term “klandestini” (clandestine) and there was confusion about what refugee status and asylum really meant, legally.

However, over time this changed. From a journalistic perspective the migration story was a perfect storm: it had an underlying human dimension and was at once a major international and local political story that was highly relevant to virtually all audiences. This meant that news managers could dedicate more resources to this field and as a result a handful of journalists managed to become semi-specialised.

This had a positive impact on the quality of reporting. Many journalists became adequately sensitised and knowledgeable about terminology and its implications. The term “irregular immigrant” started being adopted as a generic collective description, later morphing into “undocumented migrant” or “migrant”. The terms refugee and asylum seeker started being used more frequently and appropriately. The term “klandestini” virtually disappeared. A fundamental underlying problem, however, remained as the general tone of coverage never really moved away from crisis mode. The main elements of the reportage concerned four primary areas:

1. Arrivals: AAs happened in the rest of Europe after 2015, the primary focus of the Maltese press was on the highly-emotive and visually-compelling phenomenon of arrivals, with human stories about harrowing journeys as well as on the statistics of people crossing and the number of people who died or went missing. The unintended effect of this intense focus on the spectacle of boat migration is that it entrenched the sense of indefinite crisis.

2. Detention: Successive governments for years staunchly defended Malta’s detention policy which saw undocumented migrants detained for a period of no less than 18 months. This proved to be a central battleground between the political class (government and opposition agreed on this policy), civil society and liberal journalists. In the early years, conditions in the centres were terrible and they were poorly managed by untrained and often unwilling army units. Successive Home Affairs Ministers tried to limit negative exposure by barring access to the press. The move had the opposite effect of drawing more attention to the facilities which became a focal point for effective journalism that brought about substantial change in the area.

3. National Debate: Migration became the centre of a profound political debate on two fronts. The first revolved around the critical appraisal of the government by the media together with civil society. As it did with its focus on detention centres, the Maltese media managed to develop a position of strength that kept government in check on several occasions; the incumbent Labour Party had a taste of this in July 2013 when the government tried to fly a group of largely Somali asylum seekers back to Libya. Journalists broke the story early in the planning phase of the expulsion and this alerted NGOs, which formed a coalition and successfully obtained a historic injunction from the European Court of Human Rights (EHCR) to block the action. The second front concerned prevailing negative attitudes towards migrants and asylum seekers. The main political parties largely steered clear of this debate on the (correct) assessment that there were no gains to be made from such a hot potato. The battle with the anti-immigrant, hard right movement was largely fought within the realm of civil society, with some journalists taking a front line position.

4. International dimension: On the international front, Maltese governments engaged in a constant squabble with Italy over responsibility for search and rescue sometimes leading to embarrassing standoffs where both countries would refuse to assume responsibility for groups of migrants stranded on the high seas. At a European level, both countries, along with a coalition of southern Mediterranean states battled the “indifference” of northern member states, then largely oblivious to the problem. Local press coverage was more or less aligned with the position of the Maltese government.

The empowerment of the media and civil society was also a product of the vacuum left by the main parties. It was a development that cut both ways, as this same void is what opened a space for anti-immigrant movements and the far right. By 2005, anti-immigrant groups were in an open battle with a section of the media considered liberal. A year later, anonymous arsonists started torching the homes of prominent journalists, columnists and human rights lawyers. It was a troubling development that had the effect of bringing all journalists together in a rare moment of solidarity. However, it also entrenched the two blocs. The reporting of the anti-immigrant movement was almost consistently critical but it was having the reverse effect of that intended.

By antagonising the movement – which enjoyed a sympathetic ear among many Maltese even if not outright support – the far-right leaders were gaining a platform. The arsons led to some arrests and though none of those apprehended were ever charged, the process helped disperse the movement. More importantly, Maltese journalists writing in the field had learnt a valuable lesson and collectively wound down their coverage of the far right. By the time the next general election was held in March 2008 the movement lost its platform – also because arrivals are down at this time of year – and hardly featured in the election results.

Migration after Mare Nostrum

Two back-to-back disasters that took place off the Italian island of Lampedusa in October 2013 saw Italy launch Mare Nostrum, the first state-sponsored maritime mission in the central Mediterranean, whose primary task was search and rescue and not border control. This was a defining development that would effectively neutralise disputes between Italy and Malta over who should take vessels in distress because Mare Nostrum, for the first time, rescued migrants just outside Libyan territorial waters, well before they reached Malta’s Search and Rescue (SAR) area.

Unable to sustain the €9-million-a-month operation on its own, Italy terminated Mare Nostrum in November 2014. The EU’s planned successor operation was initially a much smaller border patrol that drew back EU maritime assets to 30 nautical miles off European shores. But when tragedy struck again – as predicted – this time killing an estimated 700 people in the single largest shipwreck in the Mediterranean since the Second World War, that plan was scrapped. As a result, Triton was re-launched as an unprecedented European rescue effort in the same waters earmarked by Mare Nostrum and Italy remained in charge of coordination.

This had an immediate impact on arrivals for Malta. From just over 2,000 asylum seekers arriving in 2013, the number dropped to 568 the following year, and just over 100 in 2015. The 29 people who arrived to Malta in 2016 after being rescued in the Central Mediterranean were medically evacuated. All the while, Italy was welcoming unprecedented numbers of migrants and asylum seekers.

There has been a lot of speculation surrounding a secret, “oil rights for migrants” deal between Malta and Italy to explain why Italy was now taking virtually all migrants coming from Libya. However, virtually all reporting failed to evaluate the impact that the shift in rescue zone had on Malta’s position, largely because the few articles written on this topic largely followed up on articles in the Italian press. Not a single Maltese news outlet has investigated this issue thoroughly to this day.

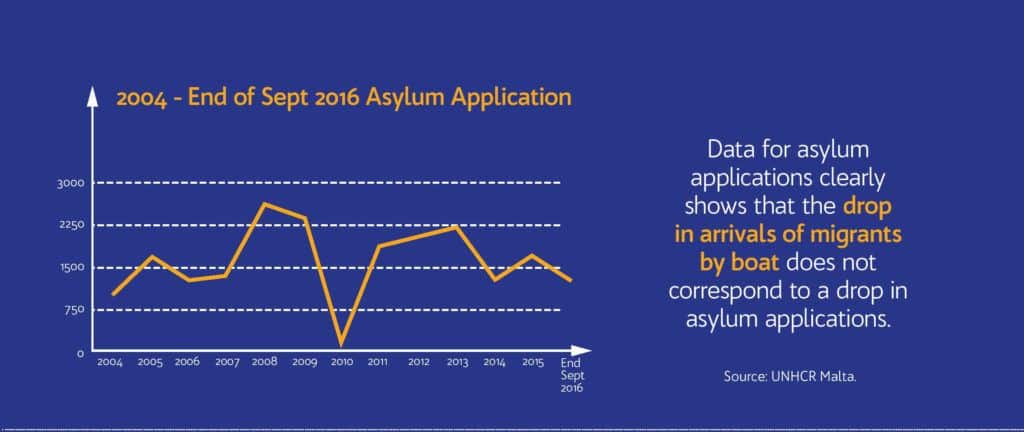

In fact, the effect of the drop in arrivals on the Maltese press since 2014 has been to deflate interest in the subject altogether. The machine that had been built around the crisis years between 2002 and 2014, now appeared to have run out of fuel. But the ‘crisis’, did not go away, if anything, it has become more complex. This is true, even when looking narrowly at the number of arrivals. In 2015, Malta processed more asylum applications than it did ten years earlier. This is because many Libyans fled to Malta on regular visas and asked for asylum particularly after the second civil war in 2014. Other nationalities like Syrians, Eritreans and even Somalis would cross from Italy by ferry or by air using fake documents; many of them after having entered Europe through the Aegean for instance. For a very long time, the Maltese press was virtually oblivious to these developments.

Journalists interviewed for this piece, consistently complained that none of them were given time to develop their own beat. Sarah Carabott, a leading and nuanced newspaper journalist in this field, said she often did much of the groundwork in her “free time”. “During my working hours I have to work on other stories, normally the sort of content that is more feasible to deliver on the day,” she says. Moreover, over time access to the migrant story has become more difficult. “I have been noticing that it has become more difficult to gain migrants’ trust in recent years,” she says.

“They have become more guarded in their interactions with the Maltese due to their day-to-day experience with racism. I confirmed this when I started telling interviewees that I faced their experiences first-hand because my husband is black. I wouldn’t normally share personal details about me, but I found that this really helped build a relationship of trust. They would really open up after learning this about me”.

The crisis machine sprung back to life towards the end of November 2016, when a group of 33 Malian men were rounded up and placed in detention pending deportation. The move followed the announcement of a review of a temporary protection status, known as THPN, which is normally granted to failed asylum seekers who cannot be repatriated.

The two issues were unrelated, but the timing caused a lot of confusion. Nonetheless, both issues are illustrative of the current problem with the coverage of migration by the Maltese media. The arrest of the Malians, in fact, is part of a European Union-wide plan to develop ‘compacts’ with third countries along the lines of the controversial cash-for-migration deal that the EU struck with Turkey in March 2016.

Had this development taken place in 2005, journalists would have pursued it more closely. But in 2015 and 2016, the Commission’s workings on migration only received cursory attention as overwhelmed newsrooms have redirected their resources towards issues that are more pressing to their audiences. The second issue concerns the broader question of integration and the living conditions of the migrants and refugees currently living in Malta. The review of the THPN status opened a debate on the fate of 1,000 or so migrants, currently residing on the island, many of them settled and in employment but who cannot really bank on a future in Malta due to the transient nature of their legal status.

Sub-Saharan African migrants themselves drew public attention to this festering problem during a protest in March of 2016 – the first occasion where migrants voiced their own concerns in a protest that was entirely a grassroots initiative.

During that demonstration, African migrants protested against the fact that despite having been in Malta for a long time – in some cases up to 15 years and more – and having established a stable household and in some cases a family, secured regular employment and paid taxes, they were being denied long-term residency. This prevented them from gaining access to such basics as a bank account, loans or the ability to plan for the post graduate education of their children let alone their pensions.

This is an urgent debate that should be taking place in the context of the greater challenge of the integration of foreign nationals generally. While the number of migrants arriving by boat has plummeted, in fact, for over a decade Malta experienced an unprecedented inflow of foreigners in the form of EU migrants and third-country nationals who travelled and settled in Malta regularly.

This revolution presents great challenges and opportunities for Maltese society in the coming decades. However, save for a few attempts by committed journalists, this great story with manifold social implications, hardly receives any attention in the press. When it does, more often than not, it is in the form of straight reporting of protest, by migrants themselves or by the anti-immigrant movement reinforcing the popular notion that migration is a crisis issue.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In this context, the highest priority for the Maltese media today is to move away from high-octane, sensational reporting of migration and towards more profound coverage of day-to-day interaction and integration of migrant and local populations. The success of this transition will eventually depend on addressing the structural issues affecting the Maltese media outlined above and which goes well beyond the issue of migration reporting. However, in the short and medium term there are actions by key stakeholders which might be useful to help ignite this much-needed transition. The following are some practical recommendations in this spirit.

1. Funding: Stakeholders such as the Institute of Maltese Journalists (IGM) should consider funding to finance immersive journalism in the field of migration. While the IGM’s effort in revising the code of ethics are welcome, there has been too much focus over the years on self-regulation rather than practical solutions to empower journalists to be more probing and far-reaching with their work.

2. Migration convention: The time is ripe not only for the Maltese press but for all stakeholders involved in migration to hold a convention that kick-starts a wide debate on the challenges Malta faces in this area.

3. Improving best practice reporting: Though progress was made over the years, there is still a lot of room for improvement on use of terminology. The moderation of online comments boards, fact-checking, sourcing of stories and interfacing with NGOs and migrants’ grassroots groups are also areas that could be improved with best-practice setting guidelines and capacity building. The IGM could play a valuable role of coordinating this effort.

4. Widening migration coverage: Newsrooms need more imagination in their treatment of migration to move into issues of integration and the importance of this process for the country from a social and economic perspective.

5. Normalisation of migrants in the public sphere: Migrants and refugees, whether they have entered Malta regularly or not, fundamentally remain trapped in the public imagination as a transient group. When they are featured in the press – even favourably – they are presented exclusively in this persona. News outlets should actively seek to include migrants as columnists or even as regular sources in mundane current affairs news that have nothing to do with migration. Maltatoday. com.mt deserves credit for being a pioneer in this field, employing a refugee to write a blog in 2014. A greater effort from all news outlets is needed in this area.

Mark Micallef is a Maltese journalist and researcher specialised on migratory flows and smuggling networks; he has done extensive fieldwork on these subjects in Libya, Turkey and Myanmar.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

References, links and sources

1 Carmen Sammut, “Media and Maltese society,” (USA: Lexington Press, 2007: 25).

2 Carmen Sammut, “The Ambiguous Borderline between Human Rights and National Security: The Journalist’s Dilemma in the Reporting of Irregular Immigrants in Malta”, (Global Media Journal – Mediterranean Edition 2:1 2007).

3 Malta had already been receiving irregular migrants by boat prior to 2001 and at that point had a developed internal smuggling industry which saw a network of Maltese criminals ferry migrants from Malta to Sicily on high-speed crafts in the dead of night. However, most of this activity concerned small groups of individuals, mostly North Africans, who pooled in the cost of a vessel or hired fishermen or seamen to sail them to Malta, Lampedusa or Sicily. Others arrived in Malta by air or scheduled ferry from Libya and overstayed their visa. The November 2011 incident was one of the very first incidents that included sub-Saharan Africans overwhelmingly and which fit the pattern of organised human smuggling that eventually established itself in the central Mediterranean.

4 The scope of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees had been restricted by the original 26 signatory countries mainly to refugees in Europe, a reflection of the historic context in which it had been formulated; the refugee crisis which followed WWII. Malta only withdrew this geographic limitation in 2001, when it accepted a whole set of new responsibilities under the 1967 New York protocol. Important provisions such as the principle of non-forcible return (non-refoulement) of refugees to territories where they could face persecution on the basis of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion were only added to the original convention after 1951. All of these legal responsibilities were pivotal to guarantee the rights of thousands of asylum seekers who travelled to Malta from Libya irregularly after 2001.

5 Henry Frendo, “Malta’s changing immigration and asylum discourse”, January 29, 2006, The Sunday Times of Malta.

6 Malta joined the EU on May 2004 after a fiercely fought campaign that included both a referendum and a general election. The country’s two main parties were divided on the question, with the incumbent Nationalist Party campaigning for and the Labour Party against. A referendum held on March 8, 2003 was won by the Yes camp but the Labour Party argued it would only be bound by the result of a General Election and the issue was decided definitively with national polls held on April 12 of the same year.

7 A popular argument used by the government at the time was that proportionately the arrival of every 1,000 migrants in a single year in Malta was proportionately equivalent to Germany receiving 200,000 people during the same period.

8 In 2005, media researcher Brenda Murphy (referenced earlier) carried out an analysis of terminology used by Maltese media. One of the highlights in her paper was an incident in which a news anchor transitioned from a news item about jellyfish to one about the rescue of a group of migrants by underscoring that both features essentially dealt with an “invasion”.

9 Mark-Anthony Falzon, “Immigration, Rituals and Transitoriness in the Mediterranean Island of Malta”, (Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38:10, 1661-1680, 2012).

10 Malta’s mandatory detention policy was changed in 2016, following the adoption of the EU’s Reception Conditions Directive a year earlier. The move followed years of controversy in which successive administrations, with the support of the then Opposition, fiercely defended the detention policy on the basis that removing it would prove to be a “pull factor”. In February 2004, live coverage of the heavy-handed suppression of protests at the Hal Safi detention centre led to an inquiry which though timid in its recommendations, confirmed that the armed forces had used excessive force on that day. In June 29, 2012, a Malian man, 32-year-old Mamadou Kamara, was killed while handcuffed by two soldiers who then tried to cover up the incident. Their trial is still ongoing.