This is a Chapter of the Study “How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration?” carried out and prepared by the Ethical Journalism Network and commissioned in the framework of EUROMED Migration IV – a project, financed by the European Union and implemented by ICMPD. © European Union, 2017.

MOROCCO

The Invisible People who Should Take their Place on the Media Stage

Salaheddine Lemaizi

On 12 September 2005, the regional weekly Achamal (“The North”) ran a front-page headline Black crickets invade the north of Morocco. Four years later, Maroc Hebdo headlined The black peril on the front page of a feature on irregular migration. These two front pages deeply shocked migrants living in Morocco and those who defend the rights of migrants. These professional blunders from a decade ago continue to define how migrants of all origins and their defenders regard media treatment of migration.

At conferences and symposiums on migration-related issues in Morocco, migrants complain about the Moroccan media’s mistakes in its coverage of migration, which they say is dominated by sensationalism and stereotypes. Since 2013, institutional changes, marked by the launch of the national strategy for immigration and asylum, have obliged stakeholders to review their approach and in particular to move beyond these two “original sins” relating to how the media cover migration. While it is unclear whether media treatment is improving, it is certainly true that it is undergoing changes that are worthy of in-depth analysis. Morocco has been a country with a history of migration to Western Europe.

Moroccan migrants settled in France and the Benelux countries from the 1940s onwards. The Moroccan press have covered their movements and the difficulties encountered by the different generations of immigrants in the host countries. Today 11% of Moroccans live outside the kingdom. In theory, at least, the Moroccan media have followed these developments.

From the early 2000s on, Morocco also became a stepping-stone on sub-Saharan migrants’ journeys to Europe. Then, beginning in 2006, Morocco gradually became a host country for these migrants. Some of them work in the large urban centres of Rabat, Casablanca and Tangier while others live in extreme insecurity. This is also true of those who “choose” to remain in the informal camps situated in Oujda or Nado (in the east of Morocco) and who often fall victim to human trafficking networks and police repression.

Moroccan society has not yet come to terms with the major changes arising from the fact that these migrants are now staying in the country and, according to some, there is evidence that racist behaviour is an everyday occurrence1 . Some media publish this racist content while others endeavour to provide a more balanced account of a complex reality. In all, the transition from transit country to country of residence2 has not gone smoothly in the media.

2000 – 2005: a history of failure

On 10 September 2013, on the instructions of King Mohammed VI, the Moroccan government launched a “once-only” operation to regularise the status of irregular migrants. This was a paradigm shift in Moroccan policy. Migration, which had until then been seen as a security question and handled by the Interior Ministry, became a public policy issue, with a dedicated ministerial department and diplomacy aimed at sub-Saharan African countries.

When dealing with migration before 2013, the majority of Moroccan media coverage was caught in the trap of sensationalism. Coverage played on the audience’s fears, used stereotypes and simplified complex issues. From 2000 to 2013, regular lapses in adherence to the code of professional conduct as established by the journalists’ syndicate were a feature of Moroccan newspaper and television reporting. Media in the first years focused on sensationalist images and journalistic coverage alternated between compassion and sensationalism.

In 2002, journalist Mustapha Abbassi from the Arabic-language daily Al Ahdath Al Maghribia produced one of the first reports from the Belyounech forest (in the north of Morocco), where irregular migrants were living. During this time there was also disastrous media coverage of incidents at Sebta and Melilia (Spanish enclaves on the African continent) in 2005. Moroccan and Spanish authorities were implicated in the death of several sub-Saharan migrants who attempted to break out and reach the two towns.

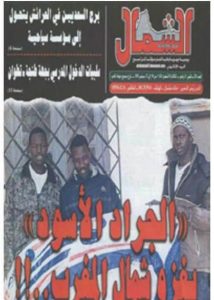

Faced with a story of humanitarian crisis, the majority of Morocco’s media, and the print media in particular, took the official, “Moroccan” side. A large number of papers simply reflected the official propaganda (Le Matin, L’Opinion, for instance). Apart from rare exceptions like Le Journal hebdomadaire, which no longer exists, or the magazine Telquel , the print media did not question this policy. The sorry symbol of this state of affairs is the front page of the regional weekly Achamal (Figure 1) and its “Black crickets.…” headline. Although a so-called “standard-setting” newspaper, run by a veteran journalist, the paper paid for this serious professional misconduct. The issue was seized by the Tangier court and its director given a one-year suspended prison sentence for “incitement to racial hatred”.

During that month other newspapers adopted a xenophobic stance when treating this issue. Examples include the daily Al Haraka [The Movement], a mouthpiece for the Mouvement populaire party, and L’Opinion [Independence], a mouthpiece for the nationalist party.

FIGURE 1

The regional weekly Achamal in 2005: “Black crickets invade the north of Morocco”. The publication was seized by the Tangier court.

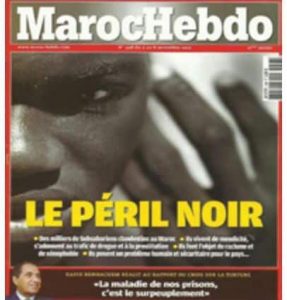

FIGURE 2

Maroc Hebdo, November 2012

2006 – 2013: Between quality reporting and “security”-focused journalism

This period of media work is marked by four major trends. Firstly, Morocco’s implementation of a new security policy to manage migratory flows. The second development was the emergence of a network of associations to defend the rights of irregular migrants. The third factor was the European Union’s steering role in shaping Moroccan government’s priorities on migration through civil society stakeholders working on the migration issue: projects were launched to support migrant communities as well as, in particular, to strengthen the quality of media coverage. The fourth development has been the to-and-fro of media coverage which alternates between quality research, investigation and reporting on the issue to coverage which is security-focused journalism, and which prepares the ground for public support of government policy and justifies the Interior Ministry’s migration decisions.

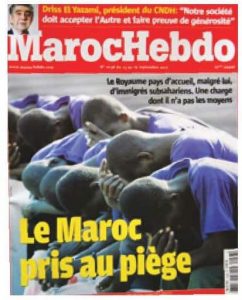

FIGURE 3

MHI repeats the offence with a sensationalist front page

FIGURE 4

King Mohammed VI decided to regularise the situation of all migrants Toutsurlemaroc.com (website does not exist anymore)

This “security-focused” journalism takes two forms. Firstly, it makes no mention of any mistakes committed by the Moroccan authorities. It may even go so far as to justify expulsions or the destruction of irregular migrants’ camps as “being part of Moroccan policy on combating human trafficking networks”. Researcher Laura Feliu Martinez sums up the situation as follows: “According to statements by human rights associations, the two public channels, 2M and RTM, help convey an image of immigrants centred on the security aspect by dwelling on successful law-enforcement operations to arrest immigrants in transit and in irregular situations”.

Secondly, this form of journalism can be seen almost daily in the newspapers’ “other news” pages. The figure of “the African” drug dealer, currency receiver or prostitution ringleader is present in the columns of newspapers with large readerships, such as the dailies Assabah, Al Massae and Al Akhbar.

Quality journalism is emerging in Morocco in the columns of the French-language press, but it is the exception rather than the rule in the Arabic-language press. The excellent work of some journalists cannot disguise recurrent instances of inappropriate language about migration still used in the Moroccan press. Many mistakenly criticise the Arabic-language press as being solely responsible for the provocative language on the subject, but in fact the Moroccan press in its entirety publishes articles that breach the journalists’ community’s code of professional conduct. The case of the front page of Maroc Hebdo International is emblematic (Figure 2).

In November 2012, it published the headline The Black peril. This cover page and the journalist’s text is an example of the confused issues and clichés on sub-Saharan populations that have been appearing in the press for the last 10 years. The article breached professional conduct, contained factual errors, used photos unsuited to the context, and was a mix of opinion and information. What makes this case reprehensible is that the paper’s management and the journalist concerned were slow to apologise. The delayed response of the paper’s management made it the subject of a social media campaign. They finally presented a half-hearted apology, but only one week later.

This deplorable front page finally prompted a debate on media coverage of migration in Morocco. It was effectively an electric shock for a fringe of Moroccan society. Within the profession, a number of journalists criticised the magazine and a member of the magazine’s editorial team publicly disapproved of the article – an extremely rare occurrence in the Moroccan press. Nevertheless, ten months later, the same weekly repeated the offence with another sensationalist front page.

FIGURE 5

Rabat News: The entire population of Rabat and the surrounding region under threat from the dangerous African Ebola disease

FIGURE 6

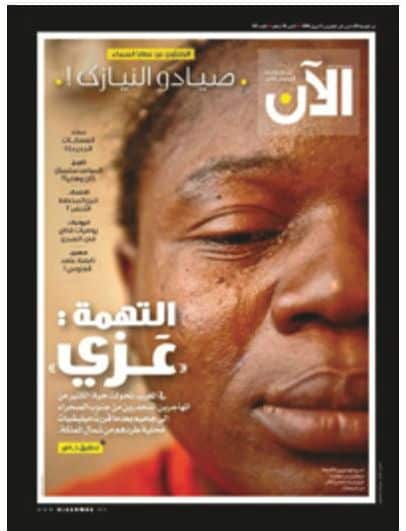

“His crime: being “Azzi’’ [negro]. This was the attention-catching title of a thorough investigation into the racism experienced by sub-Saharan migrants; it illustrates more professional treatment of migration issues by Moroccan journalists.

September 2013 to the end of 2014: “migration” becomes a trendy topic

On 9 September 2013, a watershed date for the “migration” issue in Morocco, the national human rights watchdog – the Conseil national des droits de l’Homme (CNDH) – released a report entitled “Étrangers et droits de l’Homme au Maroc : Pour une politique d’asile et d’immigration radicalement nouvelle”. The document triggered a once-only operation to regularise the situation of irregular migrants. Some of the recommendations contained in the report concerned the work of the media. For example, it exhorted the Moroccan media and journalists to “refrain from publishing or distributing messages inciting people to intolerance, violence, hate, xenophobia, racism, anti-Semitism or discrimination against foreigners”. The report and royal interest in the new migration policy, along with the government’s involvement in implementing the policy in record time, brought “migration” under the spotlight. From being an “invisible” population for many public media, migrants went on to becoming a trendy topic for all private and public newspapers. During this period the following trends were observed:

1. An indulgent attitude towards the State. Under the cover of the regularisation operation, the public media (Agence MAP and the television channels) or media close to the State are promoting government policy. The “migrant” is only there to “thank His Majesty the King” (Figure 4) and “the Moroccan people for their welcome”. Questions about how the operation was carried out are squeezed out (criteria, rejection rate, etc.).

2. Continuing Sensational treatment. Treatment of the issue continues to be marked by occurrences of racist language and breaches of professional conduct. The print media continues to convey clichés about migrants. The cover page of Rabat News (Figure 5) in March 2014 illustrates this.

3. More Professional treatment. “His crime: being a negro” was the attention-catching title of this Moroccan weekly (Figure 6). The journalist conducted an investigation into the racism experienced by sub-Saharan migrants in a small town in the north of the country. This is one of many examples of thorough fieldwork carried out by journalists. Over the year, it was noted that journalists were becoming increasingly specialised in the migration issue (Libération, Yabiladi, Telquel, and Akhbar Al Yaoum, for instance.).

The features of media treatment in 2015

The year 2015 marked a low point in public discourse on migration. A press review on articles dedicated to migration in 2015 made five observations:

1. Migration is an “invisible” subject. In 2015, few print media (paper or online) addressed the story. Irregular migration and issues related to refugees and asylum-seekers still receive scant media attention. In 12 months, based on a press review of over 400 articles, around 20 media outlets took an interest in the subject and only a handful of them (Yabiladi, Libération, Telquel, Hespress) regularly dealt with the subject and were able to put the issues into perspective. The risk is that the subject is forgotten or left aside. This arises because there are few competent journalists with a sound grasp of the thematic, and the lack of precision over the legal terminology and the various issues involved in the subject. At editorial level, the “invisibility” of the topic makes it difficult to develop a common approach that can be set out in editorial charters. Instead, we are seeing case-by-case treatment based on the media agenda.

2. Migration is an “institutional” topic. Media treatment of migration in 2015 is also characterised by a focus on news about public institutions working on the topic. The majority of articles reflect on the migrant regularisation campaign launched in 2013 or dealt with the symposia organised by the ministry in charge of migration or its national and international partners. Other articles covered events organised by international organisations to mark International Migrants Day (18 December) or International Refugees Day (20 June). This event-focused treatment leaves no room for dealing with the reality of migrants’ everyday experience. The media were also content to base their reporting on the official versions, without seeking the viewpoint of the main people concerned.

3. Migration remains a “hot” topic. Media treatment of migration in 2015 peaked in the month of March, coinciding with operations to clear and dismantle irregular migrants’ camps near the Moroccan town of Nador (in the northeast). That month, 55 articles were produced. The majority set out the authorities’ version of the facts and only a minority quoted from reports and observations made by NGOs that defend migrants’ rights. These articles stuck to the facts, but the facts as seen by the authorities. This sort of strong media mobilisation during similar events (arrests, minor news items, trials, fatalities, etc.) is not specific to the migration issue: it stems from the internal operating constraints of the press, which devotes its attention to topics primarily as dictated by the media agenda, without having its own specific vision for treating the topic. This seasonal treatment heightens migrants’ mistrust of journalists. The strong media presence only found during these events does not allow for a longer-term, more balanced, objective, humanistic treatment of the theme.

4. Migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers are noticeably absent from the print media. The press review shows the almost total absence of migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers as sources in articles dealing with their situation. It should be noted that, out of the 400 articles surveyed, only 10 drew on statements by migrants. The migrant voice is replaced by spokespeople who speak on their behalf, including the NGOs and international organisations. In fact, the migrant becomes a passive subject: “beneficiaries of humanitarian action” or people who are “deported”, “resettled” or “arrested”.

5. Hate speech on social media. The online media articles surveyed did not contain any hate speech or racist speech. Instead, the articles fell into the categories of sensationalism, stereotypes or simplification, though without supporting any racist or xenophobic discourse. On the other hand, many online users’ comments on these same articles were racist or xenophobic, referring specifically to the sub-Saharan populations living in Morocco. These expressions of hate lurk, with absolute impunity, in this Moroccan dark web.

As the national strategy for immigration and asylum (SNIA) is entering its fourth year, disappointment is running high among the regularised migrants, who are still waiting for several aspects of the migration policy announced in 2013 to take effect.

Migrants’ expectations include a legislative reform, access to health care, education and work, but also an improvement in media treatment of the subject. The main challenge facing Moroccan media is to report on progress being made to support this settlement migration and the challenges arising from this new situation, with its ups and downs. In other words, media should guide and support the migratory journey of people living on Moroccan soil in their everyday experience. There should be more focus on the day-to day realities of their lives as a next-door neighbour, work colleague, teacher, health care system user or job seeker. It is essential for the Moroccan media to discard any media treatment that reflects an image of migration solely in terms of transit or invasion. As journalist and teacher Jean-Paul Marthoz so aptly says, the media must make a choice: “Faced with such ‘loaded’ subjects as migration, journalism has a choice: either contribute to the world’s misfortune through its negligence or its indifference, or, on the contrary, play a part in defending human dignity, with journalism’s code of conduct”.

Salaheddine Lemaizi is a freelance journalist and guest teacher at the Institut supérieur d’information et de communication, Rabat (Morocco). Blog: journalinbleb.wordpress.com

References, links and sources

1 See this report: “Au Royaume de Mohammed VI, un racisme permanent et impuni”, http://www.h24info.ma/chroniques/le-maroc-de-mohammed-vi-un-racisme-permanent-et-toujoursimpuni/26898.

2 See also: “Campagne Maghrébine contre les discriminations raciales : Pour des législations nationales contre les discriminations raciales”, http://www.gadem-asso.org/campagne-maghrebine-contre-les-discriminations-raciales-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%85%D9%84%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%BA%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%B6%D8%AF%D9%91-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%86%D8%B5/

3 Le Journal hebdomadaire et Telquel, editions published on 15 October 2005.

4 Laura Feliu Martínez, “Les migrations en transit au Maroc. Attitudes et comportement de la société civile face au phénomène”, L’Année du Maghreb [Online], V | 2009, posted on 09 July 2010, viewed on 12 April 2015. URL: http://anneemaghreb.revues.org/611;DOI:10.4000/anneemaghreb.611

5 We have no intention to minimise the danger of such networks, but the coverage given to them by the press is out of all proportion to their real importance in criminal networks in Morocco.

6 Read the editorial by Mohamed Selhami, director of MHI, http://www.maghress.com/fr/marochebdo/105253 (viewed on 12 April 2015)

7 For an in-depth analysis of this front page, read Nadia Khrouz, Des « mots » aux « regrets » : qu’est devenu le « Péril noir » ? http://www.cjb.ma/268-les-archives/270-archives-editos/382-archives-editos-2012/des-mots-aux-regrets-qu-est-devenu-le-perilnoir-2082.html (viewed on 12 April 2015)

8 Wissam Boujaidani, « Péril noir », la réaction d’un journaliste de MHI, http://www.yabiladi.com/articles/details/13739/peril-noir-reaction-d-un-journaliste.html (viewed on 12 April 2015)

9 The report is available here: http://www.ccdh.org.ma/fr/communiques/le-cndh-elabore-un-rapport-sur-lasile-et-limmigration-au-maroc

10 Fouzi Mourji, Jean-Noël Ferrié, Saadia Radi and Mehdi Alioua, Les migrants subsahariens au Maroc, enjeux d’une migration de résidence, Université internationale de Rabat and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2016

11 Jean-Paul Marthoz, Couvrir les migrations, De Boeck (2011)