This is a Chapter of the Study “How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration?” carried out and prepared by the Ethical Journalism Network and commissioned in the framework of EUROMED Migration IV – a project, financed by the European Union and implemented by ICMPD. © European Union, 2017.

SWEDEN

Journalism on the Spot as Europe’s Asylum Leader Takes a Change of Direction

Arne Konig

That 2016 was a year of intensive reporting of migration in the Swedish media comes as no surprise. Sweden had become the European Union country with the highest number of arriving asylum seekers per capita after almost 163,000 asylum seekers had arrived in 2015, compared to roughly 80,000 in the previous year.

In the autumn of 2015 the government argued that restrictions were needed, to uphold “order and security” in the country. They introduced severe restrictions to reduce the numbers of arriving refugees. In a short period of time, the image of Sweden changed from a country seen as perhaps the most “generous” in Europe, concerning migration, to being one of the most restrictive. During 2016 only 29,000 asylum seekers reached Sweden.

This change was also reflected in the media. The editorial tone went from welcoming to a more negative one in relation to migrants, as problems related to migration came in focus. The SOM-institute at the University of Gothenburg, which makes yearly surveys on social questions in Sweden, found that when it comes to issues that most concern Swedes, the question of migration and arriving refugees had become the most important.

Border restrictions, identity checks and issues flowing from the arriving refugees dominated media coverage in 2016, according to a report from Novus Retriever, a Swedish survey institute. Almost 250,000 articles on the so-called refugee crisis were published. The second biggest issue was the United States election, with 150,000 news items. According to Novus Retriever there was more interest among Swedes in media coverage of the “refugee crisis” and the war in Syria. Every second person surveyed said reporting on the US election was too extensive.

Based on the debate among journalists, in media reports and academic research, one political party stands out as key to understanding why media coverage of migration has in some cases avoided asking tough questions: Sverigedemokraterna, SD, (The Swedish Democrats).

Despite its roots in right-wing and Nazi circles (which the party has tried to erase from its historical record) it is now the third largest party in the country, with 12.9 per cent of the vote in the last general election and with 49 of the 349 seats in Riksdagen, the Swedish parliament. The party’s main political goal was to preserve “Swedish values” and restrict immigration. For a long time the party only focused on migration and immigrants.

The SD was considered by many voters simply a racist party and other parties in the parliament made an agreement to block it from exerting political influence by not negotiating with or making agreements with SD. Today, this common position is no longer so strong. The Conservatives former leader, then prime minister, Fredrik Reinfeld gave a speech in 2014 where he said we should open our hearts to refugees.

But in 2016 his party has adopted many of the views of Sverigedemokraterna and the Conservative leadership no longer support their previous chairperson and prime minister on his view on refugees. This political approach, aimed at avoiding racist and inflammatory political discourse, also had an impact on media coverage of the wider issue. For a long time according to academics as well as journalists, the lack of debate on immigration among the traditional parties (meaning not SD) also starved public discussion because it led the media to not report on migration in terms of costs and in terms of problems.

When public service TV initiated a debate under the headline – How much immigration can we afford? – it led to inflammatory discussions. Many journalists as well as the public were moved instead by images of refugees arriving on the shores of Italy and Greece and the pictures of the ones who did not make it, lying dead in the Mediterranean. Emotions where strong all over Europe and media in Sweden for a long time reflected on the humanity of helping arriving refugees to find their way. One journalist, working for public service TV on assignment in Turkey to report on the refugees, even ended up bringing a young boy to Sweden and is now facing trial for smuggling the boy into the country. Right wing organisations and websites such as Avpixlat, linked to SD through one of its leading members, claim there is a conspiracy among journalists not to provide critical reporting of migration. There is even a myth that journalists made an agreement among themselves not to do any critical reporting. Among the websites hostile to migrants, and among some groups in the population, the cover up theory is strong. These groups feel they are not allowed to speak freely and that sentiment has been reinforced by the fact that traditional media, responding to hate speech and misinformation, now automatically block comments on migrant stories. It is an issue which has also led to public comments from the former conservative minister of culture, who also is a former journalist.

In general terms, the public has a high degree of confidence in public service media and morning newspapers. Nevertheless, according to the SOM-institute, around 60 per cent of Swedes do not think the media reports truthfully on migration problems. But media and journalists are under severe pressure. They are attacked by hate sites, and their credibility is undermined also by the emotional power of the migration story and the very fact that facts do not count as much as they did before on this issue.

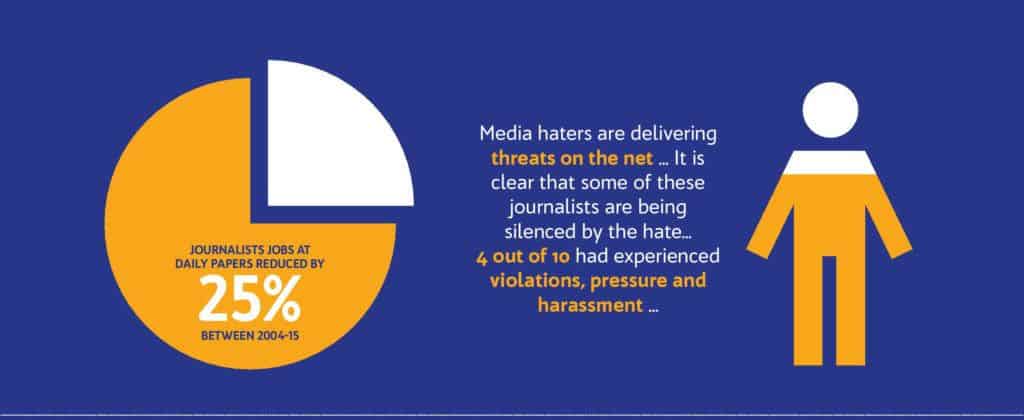

At a time when the profession of journalism is losing status, media haters are delivering threats on the net and are especially targeting female journalists. It is clear that some of these journalists are being silenced by the hate. In the summer of 2016, the Swedish Union of Journalists presented a survey on threats against journalists which showed that four out of ten had experienced violations, pressure and harassment. A quarter of them said they had not reported as they would have otherwise, due to external pressure.

Swedish journalists are often accused of bias. In the public debate they are accused of being politically left and it is fair to say they are voting for the green party and leftist ideas more than the public in general. However, repeated studies at the University of Gothenburg conclude that this does not influence their reporting. A small interview study by journalist and researcher Björn Häger suggests that journalists have, indeed, been partially restricting themselves on reporting migration. The reason is to avoid giving support to racists and to promote values supported by SD. Beyond this study, this tendency is often mentioned by journalists.

In some cases newsrooms and media have adopted guidelines not to support racist ideas in their reporting. For public service radio and TV this is a particular obligation because the network has an agreement with the state that they can broadcast freely, but must promote democratic ideas and values. In one example, when a leading SD politician spoke on TV, there were signs broadcast simultaneously giving the correct facts so the democratic values could be promoted. This issue of objective and balanced or neutral reporting is now under discussion within Swedish journalism. Traditional ways of presenting the views of opposing forces in a story is not enough, when obvious lies are presented. This is of course more of a problem for live broadcasting than for written reports.

The Institute for Media Studies, an independent body, is carrying out a study to look at how the media has reported on migration in more detail, but for now there is only information on this from an examination of the four leading newspapers’ opinion pages. That is to say the opinion pages of the papers, not readers’ letters or debate material produced by external writers and organisations. The study focused on migration and integration covering 1,000 articles from 2010 to July 2015. The conclusion is there is no evidence to support the idea that opinion pages in leading newspapers give a mostly positive picture of migration towards Sweden. The bias is not that the articles are about the positive impact of migration; it is about pointing to problems connected to migration. This is in line with research about news journalism and its strong tendency to focus on problems and negative issues. Bad news is so to speak good news, as Professor Jesper Strömbäck, in charge of the study, puts it.

In the book Migration in the Media the Institute gives some researchers and journalists the opportunity via personal essays to give their views. Their impressions vary. The debate around upholding a consequence neutral journalism is there, and for some of the writers in the book that has been and is a problem in reporting. The interpretation is that the professional values of journalists are losing ground, as confirmed by the previous study of Swedish news rooms. It is relevant to ask in these circumstances to what extent journalists are connected to the expectations of their readers, listeners and viewers.

Overshadowing this, with its own influence on the migration story, is the role of social media on the work of traditional journalists. The media community often claims that so-called click journalism is not a driving force, but in reality this sort of journalism is present as media outlets continue to publish the most read stories/most clicked stories day after day. The attitude that the priority must be given the audience what the audience apparently wants, prevails in many media outlets.

One criticism of the reporting on migration has been the lack of presentation of hard facts, and focusing more on emotional stories. This is again linked to the argument that negative sides of migration are not presented.

As an example of the hard facts discourse, the journalist Lasse Granestrand, who for three decades has been reporting on migration, in the book refers to unemployment figures for migrants and how Swedish schools are producing poorer results, perhaps due to the challenge of welcoming many migrants. And yes, the writers in the book Migration in the Media, claim the reporting has been focusing on the traditional; conflicts and problems, which is in its turn connected with the “nature” of journalism. At the same time some of the writers note the general trend in the media debate, which is that the restrictions on migrants trying to come to Sweden is all right. That has led to more negative reports in the media, relating to, for example, problems and violence among asylum seekers.

One issue that has certainly had an impact on media coverage is the social and employment crisis in Swedish journalism. The job market for journalists in Sweden is weak. In daily papers, the number of journalists has been reduced by a quarter in the period 2004-2015. Still the most common way for media outlets to save money is to reduce staff. Local media is suffering. Out of 290 local geographical areas, kommuner, 32 have no journalistic coverage at all, according to the latest yearly report from the Institute for Media studies. The Institute notes that access to information and journalism continues to be a matter of class and economic resources. The young, poor, and uneducated have the least access, and these three categories are common among migrants.

An old issue in the debate about journalists is who they themselves are, are they representative of the population? One major problem is that they are not as connected with migrants and the migrant community as perhaps they should be. Half of the total members of the Swedish Union of Journalists live in the capital, Stockholm. They are normally well educated, live in the city, not in the suburban areas with many immigrants. Many journalists for production reasons tend to leave the news room only if really necessary. Their work is done by telephone and with the help of the internet, they do not often meet the world of the migrants, or other underprivileged groups. For a long time the media has been dominated by white people and journalists only had Swedish experiences and background. Slowly this is changing, especially in public service media, where second generation migrant staff are now more present and more journalists with migrant backgrounds are entering the profession.

The media community has during the last years developed a growing sensitivity on words used to describe their subjects. But in a study on the language of the four leading newspapers in Sweden, done in November 2015, researchers claim that words that dehumanise refugees are being used. They point to reports using words like “streams”, “flows”, and speaking of a need to control the “flows of refugees”. The situation around the refugees is described as a “threat” or as being an expression of something fearful when connected to terrorist actions.

As fashionable words in social media are used to connect to the media audience, and these words change often, this is a lively debate. Migrants often accuse Swedish society of not being welcoming, not allowing them to integrate. Using the word immigrant for second or third generation swedes has been a problem. The most recent approach is to use “born in Sweden/ not born in Sweden” as a more neutral description. For example, the unemployment figure for persons born in Sweden is roughly 4-5 per cent, for persons not born in Sweden it is 20-25 per cent.

At the same time, it is clear that Swedish traditions and bureaucracy can be very hostile. Asylum seekers suffer due to an under-resourced migration authority and have to wait for a long time for a decision on their asylum request, often a year, sometimes a year and a half. During that time they are not allowed to work, and they are not given language training.

A man from Bangladesh with a job and several years in the country was forced to leave as his job at the time was not formally and correctly advertised. Another well integrated person with a job and permit to stay was not paid according to the collective agreement, by mistake, as it seems. He earned 10-20 Euro too little per month and would have had to leave the country, had he not been saved by a campaign. A young boy of colour was in December 2016 chosen to be Lucia, the traditional light bearer before Christmas, in a big department store in Stockholm. The old tradition used to be that Lucia was a blond girl and a hate campaign followed that prompted the department store to drop the idea. All of this provides scope for journalism that is informed and sensitive and that provides a comprehensive overview of the complex realities of migration. The problem remains in how to create the political, professional and public information space for the story to be told without being overwhelmed by prejudice, bigotry and self-interest.

RECOMMENDATIONS

With that in mind Swedish media could strengthen their role by supporting more effective journalism. Some recommendations on that could be:

• More Specialist Migration Correspondents: Sweden has two journalists named as migration correspondents, and both working for public service media. Given the importance of the migration story, more media outlets could be encouraged to give journalists the opportunity to become specialised on migration.

• Training for the Migration Story: Sweden used to have a good tradition of further education of journalists, but media’s funding crisis has reduced these possibilities. Journalists need to be trained in finding new information and new sources on migration and this training should be directed at reporters and editorial managers.

• Strengthen fact-based communications: The migration story is a casualty of so-called posttruth discourse in which facts are less important than emotional responses. The importance of facts and fact-based reporting is the very nature of journalism and it may be useful, using migration as a theme, to promote public debates on media literacy and how ethical journalism and fact-based information are essential for free expression and responsible public communications.

Arne König is a Swedish journalist and editor who served as the president of the European Federation of Journalists from 2004-2013.