This is a Chapter of the Study “How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration?” carried out and prepared by the Ethical Journalism Network and commissioned in the framework of EUROMED Migration IV – a project, financed by the European Union and implemented by ICMPD. © European Union, 2017.

GREECE

Media’s Double Vision as Migrant Crisis Catches the World’s Imagination

Nikos Megrelis

Prior to the 1990s the first significant migration flow of men and women to Greece came from the Philippines many of whom worked in Athens mainly as domestic workers for the affluent and upper-middle class. The Greek media as well as Greek society in general hardly noticed their presence. They worked in people’s homes for six days a week and lived elsewhere on their day off. They were rarely seen in public places and were never integrated into Greek society. They rarely troubled the police or the authorities and so, in turn, did not suffer widespread discrimination or from racist comments, either in the mass media or elsewhere.

There was a further significant migration flow from neighbouring countries in the beginning of the 1990s (from Bulgaria and Romania) and, in particular, from Albania following the death of Ramiz Alia at the end of 1991. As a result of the implosion of state authority in Albania (one day the doors of prisons were opened and all detainees were released) there was an influx of more than two million Albanians who came to Greece by all possible means in search of a better life.

The absence of any proper preparation by Greek authorities to deal with such a great number of destitute people, often going hungry, set the scene for a public backlash. Additionally, among the new migrants were criminal elements and the crisis sparked a mass media response in which racist stereotypes were often used in relation to the newcomers.

Thousands of stories in the media, both print and electronic, focused on a crime wave driven by a so-called “Albanian mafia.” Albanians were blamed for many hideous crimes and were accused of being responsible for the rise in crime at that time, although this was never corroborated by official data or evidence. http://www.astynomia.gr/images/stories/NEW/hellas.pdf.

The television news continuously broadcast sensational stories from the Greek-Albanian frontier showing terrified citizens, guns in hand, preparing to deal with Albanian crooks. Almost any crime, or any misdemeanour no matter how minor, could be attributed to the migrants irrespective of evidence or facts on the ground.

The reality was something else as the evidence in the survey “Business Activity, Risks and Competition in the Historic City Centre of Athens” conducted by the Political Sociology Institute at the National Social Research Centre, reveals. The survey debunks the myth that migrants are to be found on top of the list of offences against property and persons. In fact, the traders interviewed who were victims of attacks named foreign nationals third on the list of key perpetrators. http://www.peals.gr/component/content/article/1-category-1/746

This trend in the media was challenged by some journalists and media. This led to an easing of discrimination in the public discourse and contributed to assisting the permanent settlement over the years of almost one million Albanians in Greece. This group were economically integrated and many of those who were once farmland and construction workers became small business owners and traders.

A spike in media racism occurred in 1996, when Greece and Turkey were brought to the brink of war. But this quickly dissipated as a result of special circumstances at the time, not least because of catastrophic earthquakes in Turkey in 1999 which forged a climate of compassion in Greece. Greek and Turkish journalists set up a contact group, aiming to challenge propaganda, eliminate racist stereotypes and to prevent the manipulation of media for war-mongering. During this time whenever there was an issue in bilateral relations, Turkish journalists were hosted in Greek TV news and vice versa. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oy9z20lYzM0

The media background to the refugee crisis that arose in 2015 showed that migrants, in general, were subject to media profiling that, either openly or implicitly, involved racist stereotypes. The nature of media coverage has been considerably influenced by the activities of “Golden Dawn”, a neo-Nazi party which has organised assaults against migrants, in the spirit and style of Nazi storm troopers. This triggered sympathy from within media for the victims, although many times media noted that somehow, they were “also to blame” because of illegal street trading or being resident without a permit.

Prior to 2015 it was rare for media news reports to focus on how migrants may be victims of state bureaucracy and face high annual charges in exchange for a temporary residence permit. Equally rare were news reports on the difficult integration procedures for migrants, especially Africans and Asians, and the problems they faced in integrating economically and socially in Greek society.

The mixed messages coming from media on migration issues is also influenced by the fact that within Greek journalism there are two strong influences, one group fiercely nationalist and anxious to protect Greece, its culture, identity and history from external threats, and the other, non-nationalist tendency which sees itself as more pro-European and outward-looking. This conflict continues and should give an idea of the media context in which the migration story was placed.

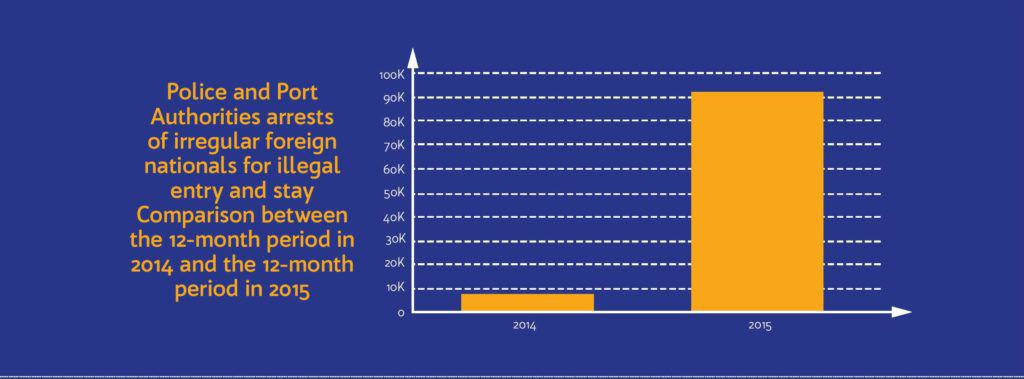

The year 2015 was marked by an influx of refugees on an unprecedented scale, sparking a humanitarian crisis that resonated across the country and was felt across the European Union. During the year, some 900,000 refugees arrived, mainly on the islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, and Kos. http://www.astynomia.gr/images/stories//2015/statistics15/allodapwn/12_statistics_all_2015_all.png

Lesvos bore the brunt of the influx, with around 512,000 refugees, compared to some 12,000 in 2014. Samos received some 104,000 compared to 7,000 in 2014, and Chios around 120,000 against 6,500. http://www.astynomia.gr/images/stories//2015/statistics15/allodapwn/12_statistics_all_2015_methorio.png

In terms of origin, almost 500,000 were from Syria, 200,000 from Afghanistan, and 90,000 from Iraq. http://www.astynomia.gr/images/stories//2015/statistics15/allodapwn/12_statistics_all_2015_sull_yphkoothta.png

At the same time, Greece saw a change in government with the coalition of the left-wing party SYRIZA and the right-wing/nationalist party Independent Greeks (ANEL). The creation of this heterogeneous coalition had within it a contradictory approach to the migration crisis. On the one hand, there is a more friendly and open approach on refugee questions from SYRIZA while, on the other, there is a more aggressive and racist rhetoric both at the local and national level from ANEL.

The capacity of the media to cover these events was not made easier by the economic crisis which overwhelmed traditional media outlets during 2015. The media saw dramatic reductions (up to 50%) in salaries, with months of arrears in the payment of wages – from 3 to 5 months – and cutbacks across the board in terms of editorial work. The non-payment of salaries provoked strikes and the capacity of media to report was reduced. The traditional media is hard-pressed, and the online and information websites provide equally bleak conditions. They pay very low wages to young and inexperienced news editors. This economic and political reality puts in context the capacity of Greek media to report effectively and professionally, not just on migration issues, but across the landscape of journalism.

The first influx

(January 2015 – August 2015)

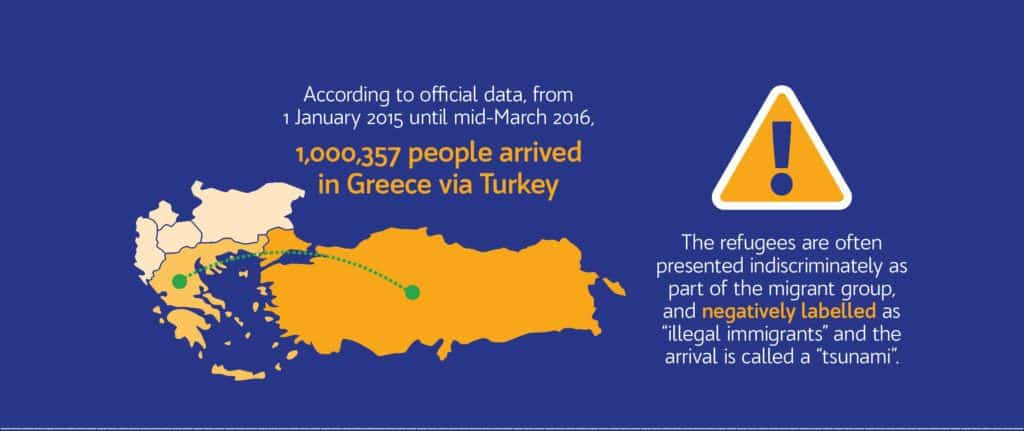

According to official data, from 1 January 2015 until mid-March 2016, 1,000,357 people arrived in Greece via Turkey. As of April 2016, some 557,476 migrants were formally registered in Greece, most of them originating from twelve countries. The Interior Ministry statistical evidence shows that legally resident third-country nationals come from: Albania (387,023), Ukraine (19,595), Georgia (18,334), Pakistan (16,578), India (14,357), Egypt (12,084), Philippines (10,468), Moldova (9,092), Bangladesh (6,301), Syria (5,799), China (4,840), Serbia (2,968). http://www.tovima.gr/society/article/?aid=795716

No statistical surveys are available on media coverage of the mass influx of the hundreds of thousands of refugees over the last two years but George Pleios, Professor at the National Capodistrian University, in a recent study published in October 2016, divided this two-year period into three segments.

He reports that in the summer of 2015, media coverage reflected the stereotypes of the past. Refugees are often presented indiscriminately as part of the migrant group, and negatively labelled as “illegal immigrants” and the arrival is called a “tsunami”. There is blatant indifference to their rights.

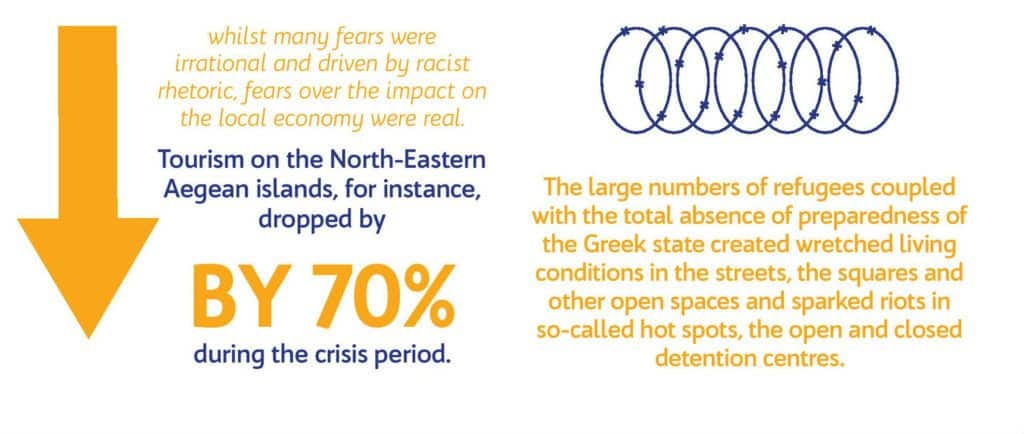

“Indeed” says Professor Pleios, “The mass media spread fear that the arrival of refugees will cause problems to public health and the local economy, for instance tourism, and that national security may be threatened, involving loss of territory to Turkey, with terrorist activity by Jihadis. It is seen as a threat to religious and cultural identity, and a demographic threat to the profile of the population”.

It is worth noting three elements behind this coverage. First, many media allegations were inspired by statements of ANEL government members (led by the president of the party and National Defence Minister of the government Panos Kammenos); second, whilst many fears were irrational and driven by racist rhetoric, fears over the impact on the local economy were real. Tourism on the North-Eastern Aegean islands, for instance, dropped by 70% during the crisis period. http://www.skai.gr/news/greece/article/321903/70-iptosi-tou-tourismou-sta-nisia-tou-anatolikou-aigaiou-/;

Third, the media reporting was also influenced by the policy failure and lack of response of the European Union and the Greek government.

The large numbers of refugees coupled with the total absence of preparedness of the Greek state created wretched living conditions in the streets, the squares and other open spaces and sparked riots in so-called hot spots, the open and closed detention centres. Most media covered these riots as threats to public order without detailed reporting on the causes of discontent. Only media favourably disposed to the opposition talked about the incompetence of the government.

The second period

(September 2015 – March 2016)

This second period is characterised by a shift with media deploying less racist terminology. The dominating picture is that of humanitarian support; of refugees fleeing war zones and being welcomed.

This sharp change of approach arose largely because the drama of refugees arriving on Greek islands became a global story with thousands of journalists from the world’s media broadcasting shocking reports, pictures and video material on the arrival and rescue of these desperate people.

Dramatic stories of desperate people circulated around the globe; pictures that touched the world with drowned bodies washed up on beaches (particularly that of Syrian boy Aylan Kurdi) were shown in the Greek media as well. This form of coverage focusing on the human cost did much to displace the rhetoric of racism.

At the same time, media noted that the vast majority of islanders were moved by the drama of refugees. The solidarity is reflected in the picture below with the three old ladies feeding a baby while its mother is having some rest. The three “grandmothers” were Nobel Prize nominees.

The softening of media coverage was also reinforced by the refugees themselves who in their numerous interviews made it clear they were declaring they were passers-by; for them Greece was a transit country and their final destinations were further afield – towards Northern Europe and mainly to Germany. Other factors also shaped the news coverage in this period. Media were influenced by the so-called diplomacy of celebrities. The Pope and the Ecumenical Patriarch, Susan Sarandon and Angelina Jolie, all travelled to Lesbos and had their photos taken with refugees, thus contributing to the eradication of the sense that refugees are a threat.

Media also dwelt on the tragic origins of the arrivals. They recognised that the vast majority of migrants were Syrian refugees with families and young children and that most of them were educated. It also helped that the Syrian refugees had only good words to say about the Greeks and the welcome they received. The Syrian war, the inhuman crimes perpetrated by ISIS and the destruction in Aleppo were all important elements in coverage that highlighted the need for humanity and solidarity and helped people better understand why Syrians were leaving their country.

During this period, Greek photographers became high-profile award winners (Yiannis Behrakis whose picture features in this report was awarded the Pulitzer prize). Their work was recognised in major international journalism competitions. Film-makers also shone, with dozens of documentary films arising from the crisis. Hundreds of photo exhibitions were organised and many theatrical plays which showcased the refugee issue were also staged.

There was also an important historical reference that influenced the collective memory for Greek media observers and society. Lesvos, the island in the international spotlight, had generations earlier been the main hosting place for Greek refugees after catastrophic events in Asia Minor in 1922 when the Greek army was defeated in the war with Turkey. The 2015 events stirred memories and public sensitivity related to that time.

Politically, the tone was less alarmist and more even-tempered. Within the Greek government, the voices of the extreme right ANEL were marginalised and their president refrained from making statements “pouring oil onto the fire”. At the same time, a picture of German Chancellor Angela Merkel with refugee children, played an equally important role. This image was extensively reproduced in the Greek Media. It reinforced what many saw as a positive message, that Germany, a country associated with negative sentiment by many because of the economic crisis, would be welcoming the refugees and they would not be staying in Greece.

The third period

(March 2016 – December 2016)

From March 2016, onwards there was a spectacular decrease in refugee flows. According to official data, during the first 11 months of 2016 some 201,156 refugees and migrants were registered for illegal entry, as compared to the 797,371 for the same period in 2015. http://www.astynomia.gr/images/stories//2016/statistics16/allodapwn/11_statistics_all_2016_all.png

There were two reasons: firstly, the deal between the European Union and Turkey by which Turkey agreed to process refugees and migrants before they were allowed to move on to Greece and, second, the closure of borders which led to as many as 10-15,000 refugees being stranded for months in Idomeni in wretched conditions.

The suffering and distress of these people and their desperate efforts to pass through the borders (which were closed from the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia); their exploitation at the hands of people traffickers and some corrupt local groups; as well as the almost total absence of support on the part of the Greek state, became a topic of international media attention.

There were many thousands of media reports, and images circulating through social media, all stimulating a wave of sympathy, compassion and solidarity. But they also sent a strong message to other refugees seeking to come to Greece from Turkey – that routes to Northern Europe are closed and that those who try to make the journey would face miserable and inhumane conditions.

The Greek media coverage at this time shifted again. It became more negative and hostile with efforts to transfer those people to other areas inside the country in places with minimum levels of organisation (such as former military camps, not operational hotels). There was uncritical and unchallenged excessive coverage of hostile public reactions, reflected at many levels but particularly in television and internet media. Kostis Papaioannout, former Secretary General for Migration Policy who resigned in disagreement over the policies, put it this way: “Idomeni was the critical point. Media changed their approach towards the refugees. They were no longer viewed as poor, miserable people and a transit problem, but rather as being in a permanent situation and that refugees represented a risk and threatened the living conditions of the locals and the country overall.”

Professor Pleios underlines this in his study. “The likelihood of having thousands of refugees stranded for a long period of time and, indeed, amidst the economic crisis, was one of the key reasons for this shift,” he says.

The situation was made no easier by the lack of will on the part of the European Union to impose quotas for the relocation of refugees, as well as the change in the stance of Germany, which became more restrictive, and the development of a sense that Greece and Italy would become “warehouses for souls” in Europe. At the same time publications began linking refugees in general with terrorist attacks, and there was more coverage of statements by religious leaders arguing that “Muslim refugees are a risk for Europe”. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18-eu-turkey-statement/

Even the EU-Turkey deal, although it sought to control the irregular flow of humanity, was reported with many reservations by the Greek media. Some interpreted it in a way to suggest that it was creating a situation whereby this neighbouring country would play a dominant role with the ability to regulate refugee flows to Greece.

In conclusion, since March 2016 the Greek media portray the refugee issue as a permanent problem and not a matter of people in transit. The tone remains ambiguous and, whether out of incompetence or for reasons of political expediency, there is almost a total absence of reporting on good practices or efforts by groups and institutions or refugees to help them have a normal life with basic standards of living, jobs, education, and access to cultural activities.

During the crisis of the past two years, the media have shown the capacity for professionalism and humanity, but they have also demonstrated how easy it is to retreat back into divisive and harmful coverage. While the situation remains unstable and without a unified political and social programme that can build public confidence, the media may find themselves becoming instruments for populism and political exploitation of public uncertainty over migration.

Nikos Megrelis is an award-winning journalist and film maker.