This is a Chapter of the Study “How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration?” carried out and prepared by the Ethical Journalism Network and commissioned in the framework of EUROMED Migration IV – a project, financed by the European Union and implemented by ICMPD. © European Union, 2017.

FRANCE

Politics, Distorted Images and why the Media Need to Frame the Migration Story

Jean-Paul Marthoz

The “migration story” was one of the most vividly discussed issues in the French media in 2016. It received front-page newspaper coverage, took centre stage on flagship television news programmes and made the buzz on social media. The European Union-Turkish agreement, the drama of migrants drowning in the Mediterranean, or the closing of the so-called Calais Jungle were major stories and, in between these highly charged events, migration in all its forms was a permanent fixture of French journalism.

The coverage was mostly driven by events, the way conventional journalism describes breaks in the news routines, and statements by government officials or their political opponents. The themes evolved as some stories suddenly emerged in the news while others lost their prominence and became repetitive.

More fundamentally, the way most media approached migration was also the result of an ominous trend: the extreme politicisation of the migration issue in the context of the rise of xenophobic populist movements. While in years past the economic ideology and the left/right divide largely determined the media’s political line, migration has become one of the most crucial “revealers” of their core values.

The migration issue is a “marker” in the battle of ideas. It crystallises broader views on other societal challenges. It defines editorial lines and puts the media’s professional norms to the test. In a country where the National Front is credited with 30% of the vote and is being increasingly “normalised” by mainstream media, the discussion has even moved away from the conventional hot button issues brandished by the far right of alleged “illegals’ over-criminality”, “social security profiteering” or “job thefts from nationals”, to deeper and more intractable questions of national sovereignty and ethno-cultural identity.

In a country where the National Front is credited with 30% of the vote and is being increasingly “normalised” by mainstream media, the discussion has even moved away from the conventional hot button issues brandished by the far right of alleged “illegals’ over-criminality”, “social security profiteering” or “job thefts from nationals”, to deeper and more intractable questions of national sovereignty and ethno-cultural identity.

The anti-Islam agenda

Migration has been hijacked in particular by the far right in order to reinforce its anti-Islam agenda. While migrants and refugees come from a diverse range of countries the major focus has been placed on Muslims and the “dangers” they represent for the integrity and the “soul” of the nation. For these radical circles the Christian heritage but also secularism (laïcité), which allegedly define France’s culture and constitutional order, are “mortally threatened” by the growing presence of Muslims “who refuse to assimilate”.

Terrorism has added a dramatic dimension to what was already a challenging issue. Successive attacks in Paris, Brussels, and Nice as well as a number of other incidents have provided a particularly dramatic backdrop to the question of migration. In fact, the traditional stigmatisation of migrants is now used as a side argument for a more fundamental rejection of the “other”, drawn less from what he/she does than from who he/she is. France has been influenced by Harvard University professor Samuel Huntington’s nativist thesis on the clash of civilizations being part and parcel of the French public debate.

The rising right Wing media sphere

The migration issue has inevitably been marked by a significant dose of polarisation. The coverage is heavily influenced by politics and the will to score political points for or against the opening of the country’s borders. Appalled by the “lepenisation of the minds” (a reference to the Le Pen family’s leadership of the National Front), the left wing and liberal media have tried to counter these discourses by practicing a form of coverage which at times tends to understate the “negatives” of migration and highlight its “positives”. Articles or programmes on the way migrants and refugees contribute to society and enrich its diversity have been regular features in a number of media outlets.

Such approaches, however, are increasingly challenged by a growing right wing mediasphere. Traditional right wing publications, like the weekly Valeurs actuelles, have increased their circulation numbers or visibility. New magazines, like the “anti-political correctness” Causeur, have also hit the newsstands.

More to the right, the so-called “fachosphere” has developed a dense and dark jungle of websites which provide a megaphone to hate-mongering and migration bashing. It also systematically attacks the leftist or mainstream media, which are denounced as tools of a “cosmopolitan elite” bent on imposing multiculturalism and undermining France’s traditional roots. So-called reinformation websites regularly publish articles on what “you will not see on TV” in order to delegitimize the moderate or liberal mainstream media.

The far right has even created its own media observatory (OJIM, Observatoire des journalistes et de l’information médiatique) which monitors the mainstream media’s alleged “anti-France” positions. Despite a cascade of condemnations for incitement to discrimination or hate speech the right wing media have clearly established themselves on the public scene.

The media crisis

The rise of far right media is benefitting from the economic crisis affecting legacy media. Many newsrooms have seen cut backs, there is less investigative journalism; fewer specialised journalists able to master all the complexities of the migration story; and less money to send reporters to countries of origin in order Finding the right formula has been difficult and ethical lapses have tainted the coverage of major moments in the migration story. The competitive nature of journalism, especially among cable news channels, has been an excuse for forgetting elementary principles. 24 Euromed Migration IV to investigate the reasons behind the decision to embark on the perilous, and sometimes deadly migration journeys.

According to a January 2016 IFOP (Institut français d’opinion publique) survey only 17% of the French public trust the media to cover immigration fairly and objectively. 43% (63% for the National Front voters) think they minimise “the problems related to migration” while 40% think that they exaggerate them. http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/80-fran-cais-considerent-que-question-migrants-va-compt-er-lors-vote-eletion-presidentielle-2017-jerome-fourquet-ifop-2540468.html

The mainstream media’s public credibility, according to the 2016 edition of the La Croix (a Catholic quality daily) barometer, remains fragile. Half of the population does not trust the accuracy of their reporting and this trend registered a 7% decline in relation to 2015. http://www.la-croix.com/Economie/ Medias/Comment-retablir-confiance-dans-medias-2016-02-02-1200737098 Only one French person in four believes that journalists are independent from political parties or big business.

Such figures produce a sense of insecurity which makes the media an easy target for the far right. They are even called the “Lugenpress”, the lying press, a slur used since the times of Nazi Germany in order to discredit the “liberal media” and their alleged “political correctness”.

The centre-right party’s (Les Républicains) presidential primaries have shown that attitudes are hardening around the issues of identity and immigration. “The candidates”, wrote centre-left daily Libération in its review of the TV debates, “have multiplied exaggerations and fibs about asylum seekers”. François Fillon, the winner of the election, “started to rise in the polls after the second TV debate, when he talked about Islamism”, said IFOP expert Jerôme Fourquet in an interview with Le Soir. The expressions of solidarity and humanity which prevailed at the time of the JeSuisCharlie marches in the wake of the January 7, 2015 attacks against the satirical weekly have given way to expressions of anger and resentment. Journalism has always been a reflection of the intellectual mood and, as Libération wrote, “the mood today leans to the right” http://www.liberation.fr/debats/2016/04/17/la-france-penche-t-elle-a-droite_1446815.

The framing of migration and asylum is strongly influenced by a shift in cultural hegemony. So-called public intellectuals like Le Figaro columnist Eric Zemmour, best-selling writer Houellebecq or the “neo-reactionary” philosopher Alain Finkielkraut have been providing an umbrella under which a number of media, consciously or not, approach issues of migration or national identity. Books decrying “France’s submission to Islam”, the rise of Jihadism in the banlieues, or the challenge to France’s national identity have become best sellers. In such an atmosphere “forms of self-censorship,” says Jean-Marie Fardeau, director of VoxPublic (and former director of Human Rights Watch, France), have seeped into the coverage under the pretext that the public is not ready to hear a discourse on the need to open borders”.

The Europeanisation of the debates

The French debates are also affected by the trans-nationalisation of the migration story. Incidents abroad, like the 2015-2016 New Year’s Eve sexual assaults on women at the Cologne train station, or the discussion of migration in the US electoral campaign with Trump’s threats to build a wall along the Mexican border, filter back into the French media and contribute to the framing, in fact to the “droitisation” (the right wing interpretation), of national stories.

“The fear that comes from Cologne might be stronger and more lasting that the spirit coming from Charlie”, Claude Askolovitch editorialised on cable TV news channel I-Tele http://info.arte.tv/fr/les-agressions-de-cologne-vues-par-la-presse-etrangere.

With the Syrian refugee crisis and the controversy around Turkey’s role in regulating the migration flow the coverage has increasingly been EU-focused, adding to the sense of a “flood” or an “invasion” and of a decreasing national control, “because of Brussels’ unelected elites”, over immigration. The divisions among EU member states have become part of the national conversation and shouting matches.

While anti-migrant politicians derided Angela Merkel’s “irresponsibility” and “German arrogance”, pro-migrant circles referred to the Chancellor’s “humane and ethical policies” to slam their own government’s passivity in front of the massive exodus from the Middle East or Africa. “If Jean Jaurès (the iconic socialist leader murdered on the eve of the Great War) were alive,” Le Monde wrote, “he would not have accepted that such a human cause did not concern the Socialist party”. Likewise, on the far right end of the political spectrum, arguments proffered by populist governments like Viktor Orban’s in Hungary or media savvy xenophobic politicians in Austria or the Netherlands have been recycled into the French national debate around the issues of national sovereignty, “Christian civilisation” and the “Islamic threat”.

The media performance

Despite the tormented and tumultuous political context “there have been a significant number of good practices,” says VoxPublic Director Jean-Marie Fardeau. “A number of media have not only fairly and humanely reported the facts but also highlighted the complexity of the issue. Such an approach has been used not as an excuse to silence inconvenient truths but as a condition for a more truthful and accurate representation of reality”.

There have indeed been examples of great reporting. The AFP (Agence France Press) news agency, for instance, has devoted a lot of resources and talent to covering this huge story. The reflections of its journalists on the MakingOf/Correspondent blogs, illustrates a commitment to public interest journalism. https://correspondent.afp.com/covering-refugee-crisis

“For reporters,” AFP writes, “covering the migration crisis is often an experience which marks them for the rest of their lives”. https://making-of.afp.com/la-tragedie-des-refugies-vue-par-lafp Public service media, in particular RFI, France Inter, Arte, and most of the “liberal” quality papers and magazines, have also been lauded for their attempts to provide thorough and balanced coverage of this most complex and divisive of news stories.

“Fact-checking” has been more widely used and applied to hotly debated controversies. For instance, more information has been provided on the real numbers of migrants, their impact on the economy, and their dependence on social welfare. Le Monde’s so-called “decoders” or Liberation’s in its Désintox columns have used that technique to debunk urban legends, fake news and rumors. In a 13 October 2016 article Le Monde’s Mathilde Fangé critically addressed six “received ideas”, such as “They are invading France,” “They are better housed than French homeless,” “They receive medical treatment at the expense of the French,” “Migrants are stealing jobs from the French”, “Migrants profit from social allocations”, and “Family reunion opens the gateway to mass immigration.” In Le Un weekly on 9 September 2015, Loup Wolff applied this sceptical approach to claims by the Interior minister of its “success” in combatting “illegal immigration”.

Many media have also endeavoured to explain and use the correct language instead of mixing all the terms in a hodgepodge of (sometimes intentional) confusion. Le Monde for instance refers to “migrants in an irregular situation” to designate the so-called “llegals” and painstakingly underlines the differences between migrants and refugees and what that means in terms of their legal status and rights. “Beware of not confusing a migrant and a foreigner,” warns the center-right daily L’Opinion. “One can be a migrant without being a foreigner if one has acquired the French nationality. One can be a foreigner without being a migrant if born in France of two non-French residents.” http://www.lopinion.fr/edition/economie/c-est-l-insee-qui-dit-l-immigration-est-tres-concentreequelques-101230

To counter stereotypes some media have also adopted a humanitarian approach and chosen to tell personal “human interest” stories. Migrants are not described as “others” but as “part of our shared humanity”. But this is not a panacea. “The priority given to the emotional and individual dimension disarms more substantive reflections. And lays the ground for the simplifying ‘solutions’ of the far right”, warns New York University professor Rodney Benson in a May 2015 Le Monde diplomatique essay on French and US coverage of migration. Even if it is an essential part of the story the good-intentioned reporting of personal dramas, be it the rescue of children at sea or the dire conditions of undocumented migrants in the Calais Jungle, may boomerang and feed instead racism and rejection. The media are operating in a society where the anti-immigration mood weighs on all events and distorts all interpretations.

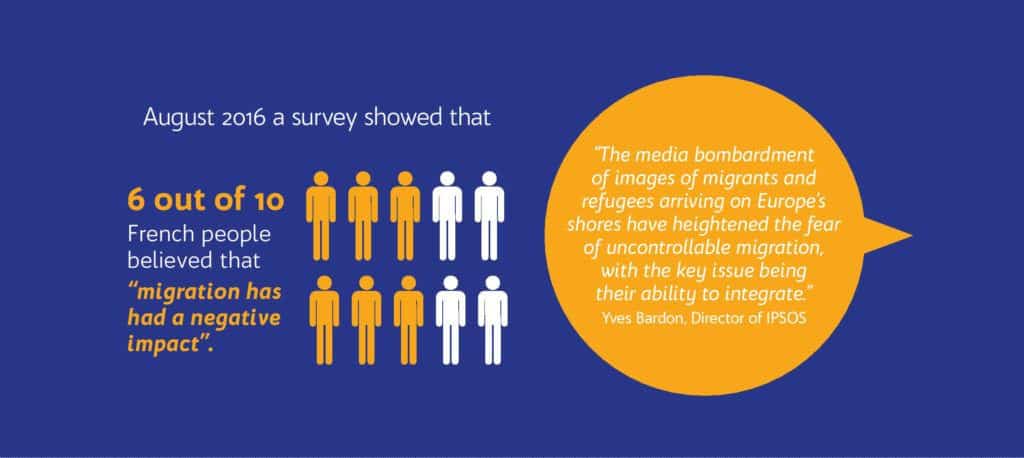

In August 2016 a survey showed that six out of ten French people believed that “migration has had a negative impact”. http://www.thelocal.fr/20160823/immigration-negative-for-france-majority-says

“The media bombardment of images of migrants and refugees arriving on Europe’s shores have heightened the fear of uncontrollable migration throughout most of Europe, with the key issue being their ability to integrate,” said Yves Bardon, a director of the French polling company IPSOS.

Ethical lapses

In any case finding the right formula has been difficult and ethical lapses have tainted the coverage of major moments in the migration story. The competitive nature of journalism, especially among cable news channels, has been an excuse for forgetting elementary principles. During the closure of the Calais jungle in October 2016 examples there were numerous examples of violations of the migrants’ dignity and privacy. Hundreds of reporters thronged to the scene, put their cameras right in the faces of the migrants, overwhelmed them with identical and often silly questions, and entered their private shelters, without asking their authorisation, just to “get the picture”. “This human subject,” wrote Le Monde’s Aline Leclerc, “should require a superior form of dignity. It is one of these moments when journalists find themselves confronted with their ethics, their capacity to resist the pressures of the mass media, and the demands of their newsroom, in order to find a balance between news gathering and respect for the other.” http://www.lemonde.fr/actualite-medias/article/2016/10/27/journalistes-a-calais-la-loi-de-lajungle_5021114_3236.html

Paradoxically, in an age dominated by the discourse on globalisation, the migration story, at least in many mainstream media, is often covered in fragments, as separate stages.

The battle over numbers has been particularly sensitive as they seem to provide a scientific element to an otherwise highly ideological discussion. “If there is a domain where framing on the basis of figures is particularly delicate, it is migration,” writes demographer François Héran in Les Cahiers français, a journal of La Documentation française. If precise and pertinent figures on migration and especially undocumented migration are hard to come by, French journalists can rely on a number of official agencies, like the OFPRA (Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatrides) or the INSEE (the national institute of statistics).

But in a country which is reluctant to allow the collection of ethnic statistics and where, as François Héran puts it, “politicians are affected by a staggering lack of statistical culture”, the politicisation of the debate blurs everything. In right wing media where the concept of “Français de souche” (of old French descent) is pervasive, figures on migrants and foreign-born residents are often mixed up with those of non-white or non-Christian citizens, even if they have been in the country for generations.

A narrow focus

The approach in many media has often been narrowly focused on the problems associated with migration. “The general background noise has been that migration is a problem and a threat,” says Jean-Marie Fardeau. “Many media have also followed the government’s communication policies, mainly related to security issues, while a very fragmented civil society was at pains to propose a powerful counter-narrative”.

The coverage has generally been triggered by two classic hooks of journalism: political controversy or dramatic images. Politicians are often driving the story and the looming presence of the far right has regularly led to statements which distort realities and degrade the public discourse. Images are also a trap. They may sometimes reflect compassion when they show survivors of capsized boats in the Mediterranean or corpses of children on a beach.

But many such images can also be subverted and framed as another indicator of the themes of “invasion” or of the refugees’ “irresponsibility.” The constant diffusion of images showing long columns of asylum seekers on the Balkan routes or of confrontations along hastily erected fence lines is a case in point of ambiguous coverage.

Few media outlets regularly address broader issues, like remittances, diaspora networks, the challenges of migrant children’s education, or human trafficking. The global aspect of migration is barely treated. Few examine the push factors in migration. Few, for instance have covered the political situation in Eritrea or Sudan which may help explain the presence of refugees from those countries in the boats crossing the Mediterranean. Even fewer cover transit countries’ policies or lack thereof, in Libya, for instance.

More fundamentally the deeper roots of emigration are rarely thoroughly addressed. “Beyond the migrants’ difficulties,” writes Professor Rodney Benson, “journalism should analyse the way the world organisation of the economy as well as the foreign, trade and social policies of Western countries like the US and France favour emigration from the South”. Paradoxically, in an age dominated by the discourse on globalisation, the migration story, at least in many mainstream media, is often covered in fragments, as separate stages. The dots are not connected although migration is one of the most emblematic symbols of a globalised world which hesitates between opening and withdrawal, exchange and confrontation.

The role of journalism is all the more important since many perceptions about migration are born and prosper in social media where fake news and hate speech proliferate. Coverage of migration is a reminder not only that journalism matters but also that it must regain the power it has lost as a credible gatekeeper and a respected framer of one of the most crucial stories of our time.

Jean-Paul Marthoz is a Belgian journalist and writer. He is the author of Couvrir les migrations (covering migration), De Boeck Université, Brussels, 2011, 240 pages.