Malaysia: State power, bribery and internet pollution of journalism

By Steven Gan

In 2001, British tabloid The Mirror sacked two writers for promoting companies in which they owned stock in their ‘City Slickers’ column. But the newspaper’s editor Piers Morgan, who made a killing by buying shares in one of the companies tipped by the column, was left unscathed. Morgan had spent £20,000 for shares in hi-tech company Viglen Technology, whose stock was tipped to rise by his newspaper the next day. He made a quick profit when he sold his shares days later. However, the proceeds were donated to charity after the scandal broke.

Morgan denied any wrongdoing and was later cleared by a government inquiry. The Mirror’s other journalists — Anil Bhoyrul and James Hipwell — were not so lucky. After a seven-week trial in 2005, they were found guilty of market manipulation.

Like their British counterparts, Malaysian editors are not immune to such temptations. There have been suspicions, speculations and rumours of similar chicanery in this emerging Southeast Asian country.

Indeed, some would go as far as to accuse the business sheets in Malaysian newspapers for being no more than public relations arm of major companies. Business editors were said to receive offers of shares and other kickbacks to put a gloss on the performance of certain companies in their newspapers.

When journalists play the market

No one could really pin a finger on it. Not until Nov 1, 1995. On that day, two major Malaysian dailies — The Star and The Sun — printed an analysis of the ailing food and engineering company Innovest when its shares were traded in the stock market after a two-month suspension.

The analysis in The Sun appeared in the ‘Hawkeye’ column, a regular commentary that appeared in its business pages. While it carried no byline, most believed that the column was written by the newspaper’s editor-in-chief Philemon Soon. The same analysis in The Star carried the byline of its business editor PY Chin.

What was intriguing was that the two pieces were, but for a few words in their opening paragraphs, almost exact carbon-copies.

Both articles were to run in three installments over consecutive days. The calumny was discovered almost immediately and an embarrassed The Star published the second instalment of the series, but pulled out the final part. The Sun, however, put on its brave face and ran all three parts, including the second part which was again exactly the same as the one that appeared in The Star.

To this day, nobody knows who penned the piece. It is, however, unlikely, though not impossible, that both Chin and Soon colluded to run the three-partners in their respective newspapers. Soon was assistant to Chin for a number of years in The Star.

But surely they were not that stupid. Another theory is that the piece could have been written by a stock analyst, or perhaps even Innovest itself. Indeed, companies prefer “independent” analysis of their stocks, however, it’s better still, if it can be written by top newspaper editors.

If that was the case, both Soon and Chin were guilty of a heinous crime in journalism — plagiarism. But this was, of course, more than a simple case of plagiarism.

It exposed the murky and deeply disturbing conditions in which today’s journalism operates. We will never know whether the two editors received kickbacks for “services” rendered. We will never know who actually wrote the three-part analysis. We will never know how the two editors got hold of the articles.

We will never know because the scandal was kept completely under wraps. Such blatant abuse of their editorship should have become a public scandal in Malaysia. It wasn’t.

There wasn’t a squeak from Malaysia’s many watchdogs. There was no criminal investigation by the police and The Securities Commission, whose role is to examine cases of insider trading and the manipulation of the stock market, did not bat an eyelid.

The National Union of Journalists, an organisation more concerned with bread-and-butter issues than press freedom, kept mum over the affair.

Despite the clear evidence of wrongdoing, all the responsible bodies sat on their hands and remained silent. This could be because while The Star and The Sun are rivals, they share common political interests. The Star is owned by a political party that is part of a ruling coalition that has been in power for more than half a century and The Sun is owned by a tycoon who boasts of close ties with the government.

Both editors got away with a slap on the wrist. Soon resigned a few months later and Chin was moved sideways in the editorial hierarchy and resigned quietly a year later. Insiders say they were nudged out by rivals who took the opportunity to squeeze them out. It was not because they had violated a cardinal rule of journalism.

Back in the UK following the shares scandal, The Mirror barred its editors and financial journalists from owning shares, apart from shares of the group’s newspapers. The Press Complaints Commission also launched an investigation. Journalists, after all, are forbidden to make monetary gain from the information they have received in advance of publication.

But no such measures arose in Malaysia. By keeping a tight lid over its own wrongdoing, the Malaysian media has left undisturbed the cosy relations between journalism and big business which remain to this day.

The complexities and paradoxes of media in Malaysia

Malaysia is a country with its fair share of complexities and paradoxes. It is multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, multi-religious and multi-lingual. Some 63 percent of the population is ethnic Malay; 25 percent ethnic Chinese; 7 percent ethnic Indian; and 5 percent are of other ethnic groups. The majority is Muslim, while 40 percent — which represents a sizable minority — is non-Muslims. The people speak a multitude of languages including English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil.

Malaysia is an illiberal democracy. We have freedom of speech, but no freedom after speech. There is freedom of movement, but no freedom of assembly. We have elections every five years, yet the same government is voted into power, time and again. There is a plethora of publications — about a dozen or so newspapers in four major languages — but no free press.

Although the constitution guarantees freedom of speech, it also allows the government to impose restrictions, as it deems necessary. This has led to a litany of laws that severely curb freedom of expression.

But while the government keeps the media on a short leash with repressive laws, it has decided not to do the same with the Internet, not because it is more open to political dissent online, but because, it has no choice; censoring the Internet would undermine economic ambitions and would cut off the country’s lifeline to the future.

Malaysia is one of the few countries, apart from a handful surviving communist regimes, which has not seen a change of government since independence from Britain almost 60 years ago. The government is able to hold on to power through skillful use of carrot and the stick policies, a manipulative mix of populism and social controls bolstered by repressive legislation. This is particularly seen at election time when it exercises sweeping control over the money, political machinery and media needed to decide the outcome. It is a simple yet winning formula in which a fearful electorate votes without hope.

Media as mouthpieces of government

Until recently the government required the annual applications of all printing and publishing permits, thus keeping print journalism under control, but due to public pressure, this mandatory renewal of licences was repealed in 2011. This change is significant; it offers hope of a change of direction. But other draconian restrictions remain. The government has the absolute right to suspend or revoke printing and publishing permits. And its decision is not subject to review nor can it be challenged in court.

Licences are given to individuals who can be trusted to toe the government’s line. Malaysia is a country where most media are either directly or indirectly owned by the government or ruling political parties. This ownership regime allows the government to exercise another layer of control.

Media Prima, the country’s biggest media conglomerate, operates all four free-to-air television channels in Malaysia. Through this, it controls almost 90 percent of the nation’s free-to-air advertising. The company also owns two major newspapers – English-language New Straits Times and Malay-language Berita Harian. It operates in monopoly conditions because there is no restriction on cross-ownership of news media.

Media Prima is also linked to United Malays National Organisation (Umno), the biggest political party in the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition. At the same time, Umno directly owns a slew of Malay-language publications, Utusan Malaysia daily and Kosmo! newspapers as well as a number of magazines.

The Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), the second biggest party in the BN ruling coalition, owns the nation’s biggest English-language daily The Star, and two radio stations. The Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), the third biggest party in the BN coalition, controls Malaysia’s oldest Tamil-language newspaper Tamil Nesan, among others.

All the major Chinese-language newspapers — Sin Chew Daily, China Press, Guang Ming Daily, and Nanyang Siang Pau — are owned by timber tycoon Tiong Hiew King through his publishing arm, Media Chinese International.

Tiong, who sees himself as Asia’s Rupert Murdoch, has a number of media organisations in the Asian region under his belt, including Chinese-language newspaper Ming Pao in Hong Kong. In Malaysia, Tiong’s other flagship company, Rimbunan Hijau, is a major player in the logging business and it relies heavily on the award of timber concessions by the government.

In 2001, MCA sought to strengthen its grip on the media by buying two of the four Chinese-language newspapers — China Press and Nanyang. But the controversial deal ignited stringent protests and a mass boycott from the public, forcing the political party to later divest its controlling shares in the two dailies to Tiong.

Astro, which has a complete monopoly in satellite television, has the largest pay-television subscriber base in Southeast Asia. It also owns eight radio stations, with a combined audience share of more than 50 percent. It is owned by Ananda Krishnan, Malaysia’s second richest man with a net worth of 11.2 billion dollars, according to Forbes magazine. Like most tycoons in Malaysia, he is a close friend of former premier Mahathir Mohamad.

Another tycoon, Vincent Tan, who is among the top 10 of Malaysia’s richest, owns free English-language daily The Sun. Tan, also a crony of Mahathir, has close business ties with the BN government through a number of plum contracts and concessions, including gambling. He also owns a British Premier League club, Cardiff City.

It is through this web of media ownership and restrictive laws that the government has operated a complete monopoly on public access to truthful information, until the arrival of the Internet.

The government, being a major advertiser, is a major source of revenue for many of these media. The government blatantly channels taxpayers’ money to the media owned by political parties, many of which make sizable profits. Put simply, they serve a double purpose — while these companies help to disseminate government propaganda, they also contribute to the parties’ finances.

A content analysis of political advertising in the 1999 general election found that while full-page advertisements backing government candidates appeared in most major daily newspapers, nearly all opposition advertising was refused.

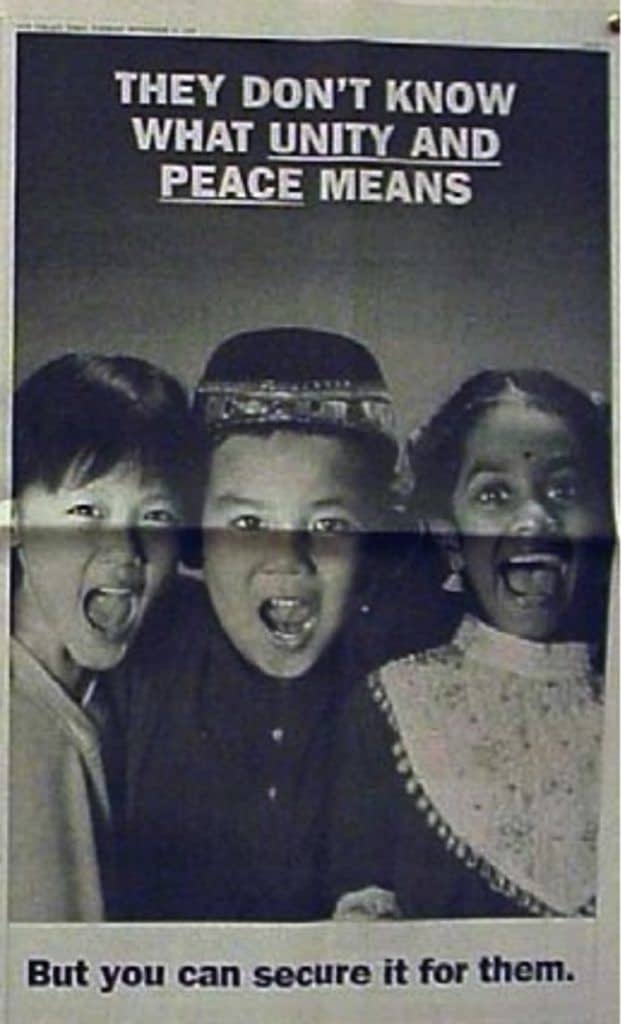

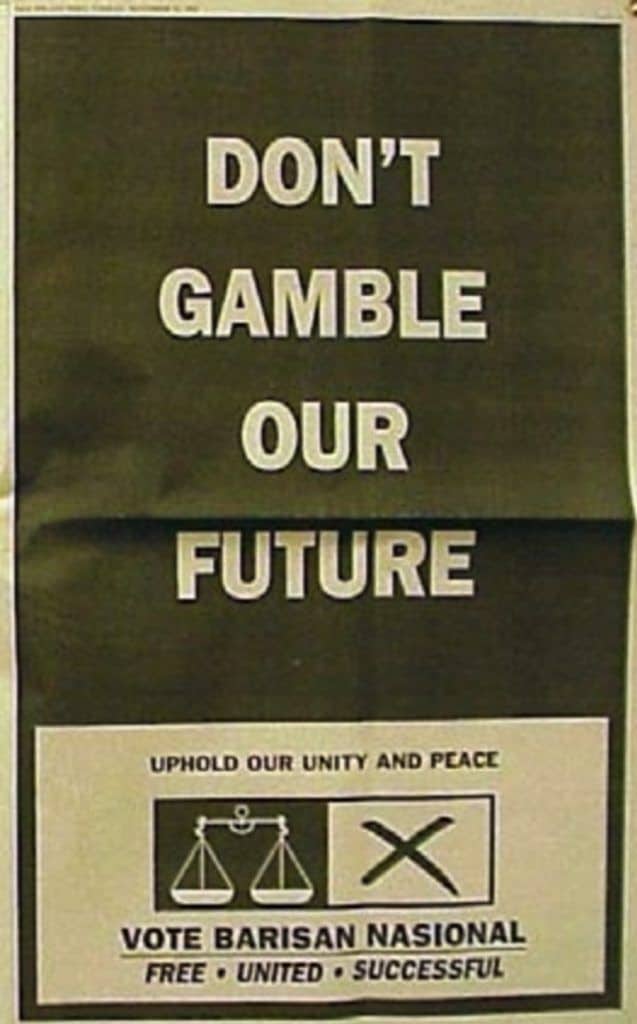

The study’s author Rick Shriver from Ohio University, said in the weeks preceding the elections, BN ads appeared on every other page of the Umno-linked New Straits Times [see images], while no opposition advertising was allowed.

The opposition has often complained that government-controlled media repeatedly refused to carry their election advertisements. Of the opposition advertisements that appeared, most were edited by newspapers that carried them.

According to Shriver, political advertisements by BN play on the themes of threats to national unity, warnings of civil unrest, and heightened concerns that a weakened BN could ultimately lead to an ineffective government.

“Malaysia’s media campaign laws are such that political advertising and its sponsorship need not be identified,” he said in Ownership, Control and Political Content (2003). “Pro-Umno television advertisements extolling the progress and stability achieved by the party had the appearance of documentaries, television news stories, or public service announcements.”

Shriver cited an anecdotal example: “One notable television spot airing in the weeks preceding the election featured a series of stills depicting obvious signs of Malaysia’s growth and development, such as the new Kuala Lumpur International Airport, the Sepang Formula One race circuit, and the Petronas ‘Twin Towers’, interspersed with photos of a smiling [then prime minister] Mahathir attending various functions and meeting with Malaysians of various ethnicities.” The television spot contained no indication of its sponsorship.

“But it appeared to be a response to criticisms of Mahathir’s economic policies. The spot suggested that Malaysia was prospering because of those policies and despite the predictions that they would fail,” said Shriver. “At the same time, nearly all major dailies were reporting that racial equality, literacy, economic development, prosperity, and national tranquility were the products of Umno, and could be sacrificed if the opposition were to succeed in the election.”

The role of ‘envelope’ journalism

While government advertising in traditional media is an indirect form of electoral corruption, there are also cases of in-your-face bribery of journalists at election time. In the by-election in the east-coast constituency of Kuala Terengganu in 2009, for example, RM300 (100 dollars) cash was distributed in unmarked envelopes to more than a dozen journalists by a government information department’s media centre.

Four journalists from Malaysiakini, the independent news portal, took the envelopes without knowing they contained cash. On discovering the money, the four immediately returned the cash. Several other journalists did the same.

Some later lodged a police report on the attempted bribery but the Information Ministry strenuously denied giving money to journalists. Ministry press secretary Hisham Abdul Hamid said they had never directed officers to give out cash. “This has never been the practice of the Information Ministry,” he told national news agency Bernama.

This has been the standard response from the government. Only a year earlier, the Information Minister Ahmad Shabery Cheek squashed the accusation that Malaysia practised ‘envelope journalism’ — a euphemism for bribing journalists.

Speaking at the launch of World Development Information Day in 2008, the minister said he was perplexed that although Malaysia had achieved “tremendous progress” in income level, infrastructure facilities, investment opportunities and more, it was nevertheless ranked far below in the World Press Freedom index — an annual survey compiled by Paris-based Reporters Without Borders.

“Malaysia has been undeservedly ranked as a country with little press freedom, very much below many other countries known to be aid-dependent and not even among the top 20 trading nations,” he said. “This sometimes begs the question whether absolute or near-absolute press freedom will bring about greater well-being for the people.”

The minister said some countries which are ranked higher in the press freedom index may not weigh in equally with their corruption index. He refrained from providing examples of the supposedly corrupt countries but said it is a “well-known fact that some countries… practise ‘envelope’ journalism”.

“This shows that the connection between a free press and battle against corruption is not clear. The media which is supposed to keep watch on the government, turns out to be crooked and corrupt as they accept ‘envelopes’ from popular figures and in turn provide more coverage,” he explained. He reiterated that such practices did not exist in Malaysia.

The journalists who received cash stuffed in white envelopes a year later proved him wrong. Again, no action was taken. While the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC), a government agency, was tasked to investigate the matter, no one was punished, despite investigators being given the name of the person who allegedly distributed the money to the journalists.

Cleaning up their act

It is clear that much of the corruption in the Malaysian media is due to the nature of media ownership and this will remain so without major restructuring. This is not likely to happen anytime soon.

However, some media organisations are implementing in-house policies to check such corruption. One of these is the no gifts policy. For example, Malaysiakini employees are not allowed to accept gifts or gratuities above a certain value from any individuals, organisations or corporations. Gifts are politely returned, and should that be not possible, journalists are required to declare gifts above RM10 (3 dollars) to the office. The value is intentionally kept low so that journalists must declare almost all gifts.

These gifts are then auctioned off among Malaysiakini staff at the year-end staff party. The money raised is given to a charity of their choice.

Native advertising and editorial: an unhappy mix

While traditionally media organisations observed a separation between news content and advertising, the wall between the two is becoming porous as a result of stiff competition for audience, especially those in cyberspace.

In the Internet, advertisers have more bargaining power than ever. They can now track not only how many people are looking at a page, but which part of the page readers are looking at, and how long they stay on the page. This puts tremendous pressure on media to deliver eyeballs to advertisers.

While advertisers are increasingly migrating online, the bad news is that it is not media companies that gain, but technology companies. Last year, online advertising in United States — at 42.8 billion dollars — commands the largest share of the market, surpassing traditional television for the first time.

“Kuala Lumpur city sightseeing” by Christian Haugen (https:// ic.kr/p/6eMqqA) is licensed under CC BY 2.0

However, the online advertising landscape is very different from the traditional media. Competitors include those which are not strictly content providers — Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Microsoft and AOL, for example. Advertisers no longer rely on journalism to deliver their audience as they did with old media. Search engines alone control almost 50 percent of the market. Indeed, none of these top five online companies are media companies. In the US, 10 companies control over 70 percent of the online advertising market, much of it drained from traditional media sources.

They and 45 others control over 90 percent of the online advertising market. Anyone outside this elite group faces intense competition for a relatively small pot of money. Moreover, media companies are competing directly with global brands, not just local brands. For many media competition for online advertising is so acute that digital media economics may not support professionally produced journalism.

In addition, advertisers are actively seeking to break the wall separating news content and the selling of their products and services. This is the genesis of so-called native advertising which, unlike its ‘advertorial’ predecessor, does not indicate to the audience that what they read or watch are advertisements.

According to an advertising agency, “Native advertising is sponsored content which is relevant to the user experience, not interruptive, and looks and feels similar to its editorial environment.” It is seen as not-so-intrusive and the advertisement does not engage in hard sell or ‘buy me now’. These native advertisements are served as a part of the content on the website and mirror the website’s look and feel.

Using cutting-edge technology, advertisers can now insert their content into news content seamlessly. To unsuspecting news consumers, it appears as if the advertisements are part of the editorial content.

Chia Ting Ting, head of advertising in FG Media — a wholly-owned subsidiary of Malaysiakini — warns that such advertisements have the potential of undermining public confidence in independent journalism. She says other pressures from advertisers include the direct demand for media to interview top officials and to publish news stories involving their companies in return for their advertisements. As media compete for a shrinking pot of money, many succumb to these demands.

Unfortunately, there is no media watchdog in Malaysia to keep media honest. The likes of The Mirror’s Anil Bhoyrul and James Hipwell in Malaysia will never be investigated, let alone punished.

Investing online for a change

Malaysia is held up by many researchers as an interesting case study on press freedom in an authoritarian environment and in promoting the Multimedia Super Corridor — a Silicon Valley-type project in Malaysia — the government promises not to censor the Internet.

This unlikely situation has allowed a profusion of online news websites to emerge, chief among them is Malaysiakini. Launched in 1999, the subscription-based news portal is the country’s oldest. Since then, it is joined by other similar websites seeking to replicate its success.

However, many news websites find it hard to survive. Malaysiakini, generates revenue from a mix of subscription and advertising, but other websites offer their content for free and are burning money. Many received support from deep-pocket anonymous funders who invest their money in return for political influence.

Given this, the cyberworld is no different from the real world. As big media conglomerates move online, it is expected that the control and domination which we see in the real world will be reflected in the online world as well.

Advertising alone will not be able to fund independent news reporting. News consumers will have to start paying for news, and if they don’t tycoons are ready to pay for journalism, but at a price. When that happens it will be the tycoons who get to enjoy press freedom, not Malaysian citizens.

In the cut-throat world of media advertising, ethical journalism is weakened by the compromises of media owners and advertisers. But ethical journalism is a value that must be cherished, protected and fortified if media are to maintain public support and democracy in Malaysia is going to prosper.

Main image: “The People’s Paper” by Chelsea Marie Hicks (https:// ic. kr/p/9kTejX) is licensed under CC BY 2.0