Fake News: It’s Not Bad Journalism, it’s the Business of Digital Communications

Aidan White

It is currently the major talking point in media and politics, but the debate over fake news is confused by a misunderstanding about the phenomenon, its origins and why it poses a threat, not just to journalism but to the framework of democratic pluralism.

To begin with, it helps to know what we are talking about, so a definition of fake news might be useful. Donald Trump yells his own definition at press conferences – it’s any journalism or reporting that he disagrees with.

“That’s fake news,” he shouts at any unfortunate reporter or representative of a news organisation that contradicts him or his entourage.

When the President of the United States makes baseless claims and labels accurate reporting as “fake” and when his staff expound theories of “alternative facts,” the challenge to journalism and its values could not be more menacing.

Whether it was intended or not, Trump’s lacerating attack on his media critics has opened up a debate about truth and trust in public communications, even if his targeting of journalists and media is wrong-headed and politically dishonest.

The idea that the current crisis of fake news is rooted in the mistakes of slip-shod and sometimes incompetent journalists is a lazy, self-serving political distraction from the real debate we need to have about the threat to democracy posed by the fabrication, circulation and marketing of false information and malicious lies.

So let’s begin with another definition. Here’s one that the Ethical Journalism Network has developed:

“Fake news is information deliberately fabricated and published with the intention to deceive and mislead others into believing falsehoods or doubting verifiable facts.”

If we accept this view it becomes easier to identify information that should be troubling for anyone who cares for democracy, free expression and responsible public communications.

This definition is useful: It sets a standard for defining propaganda in politics; misinformation in advertising; distortion, exaggeration, malice and self-serving communications in any form of public discourse.

Of course, journalism shouldn’t be let off the hook. There has always been fakery and misinformation in the news business. Journalism has many maverick reporters who make up news stories, or massage facts and quotes. But these are rogue reporters who, when exposed, are disciplined and sent packing.

Reputable editors will be the first to admit that journalism is a rough and ready profession and it is inevitable that in the frantic process of news gathering and the rush to meet deadlines mistakes will be made.

But journalism worthy of the name owns up to its errors. The proliferation of “clarification and correction” columns in news feeds and printed publications demonstrate that accuracy and reliability remain central to the cause of building trust in journalism as a public good.

The threat posed by fake news does not emerge because of the work of journalists, despite the best efforts of political leaders like Trump, or Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan or Vladimir Putin in Moscow, who attack independent journalism and dissident voices not to defend truth and pluralism but instead to intimidate and bully media into following their own political agenda.

But there is no denying that false information is a disruptive force in modern communications. And there is also no doubt that it poses a threat to democracy as revealed by the role played by false narratives in last year’s United States Presidential election and the British referendum on European Union membership.

A major part of the problem lies in the deeply flawed nature of the modern culture of communications and more precisely in the business models of major Internet platforms such as Google, Facebook and Twitter.

These networks circulate information in a value-free environment which makes no distinction between high-quality information sources such as professional journalism and the malicious lies of people generating hate speech or even those who circulate and stream horrifying images of torture, murder and other unspeakable brutalities that humans are capable of.

Using sophisticated algorithms and limitless databanks providing personal access to millions of subscribers, this business model is driven by “viral information” that spreads and delivers enough clicks to trigger digital advertising. It matters not whether information is true or honest; what counts is whether it sensational, provocative, and stimulating enough to attract attention.

This model encourages a new entrepreneurial spirit in the world of information, but not one that favours responsible communications and ethical journalism. No one should be surprised, therefore, that tech-savvy teenagers in Macedonia were able to use Facebook’s platform to circulate fake news stories around the United States election, and it was, after all, a perfect business opportunity.

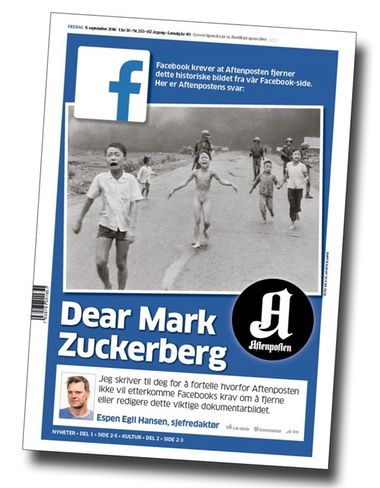

The use of algorithms and robotic techniques to manage and distribute information regularly gets the big tech companies into hot water, even when they are trying to do the right thing. Last year’s censorship by Facebook of an iconic Vietnam War era photograph is a case in point.

This arose because of attempts by the company to take down exploitative and anti-social pictures of naked children, but it led to a stand-up row with a leading editor and angered media leaders and free speech advocates worldwide.

Digital robots are useful, they argue, but they can’t be encoded with ethical and moral values. Clearly, the best people to handle ethical questions regarding online content are sentient human beings, however the digital business model eschews any significant role for journalists and editors to do this work.

The threat to the public information space is self-evident, but it’s not just public interest journalism or people’s right to access reliable information that is at risk.

The inventor of the worldwide web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, warned recently that the business model of online platforms is also potential threat to democracy, particularly at election time.

He says that the sophisticated techniques used to promote online political advertising may be unethical in the way they target people and how they direct voters to fake news sites.

He used the 28th anniversary of the worldwide web to speak out over the dangers that arise when most people get their information from just a few platforms and the increasing sophistication of algorithms which draw upon rich pools of personal data for political campaigning.

In an open letter (on March 12 ) he wrote: “One source suggests that in the 2016 US election, as many as 50,000 variations of adverts were being served every single day on Facebook, a near-impossible situation to monitor,” he wrote. “And there are suggestions that some political adverts – in the US and around the world – are being used in unethical ways – to point voters to fake news sites, for instance…. Is that democratic?”

It’s a question that is worth asking at every level of politics.

The development of business models driven by algorithms which put clicks before content have already drained the life-blood of advertising from the traditional global media industry and weakened the capacity for ethical journalism; they have opened the door to a new culture of communications in which truth and honesty is obscured by fake news, bigotry and malicious lies; and they have legitimised the notion of fantasy politics which can encourage ignorance, uncertainty and fear in the minds of voters.

These realities take the fake news debate well beyond the grumbles and resentments of publicity-seeking Presidents who want to tame the press. They raise bigger questions that not only concern the future of journalism but also the nature of democracy itself.