Turkey: Elections in a Fake News Climate

This article was republished with permission of the Green European Journal. You can read the original here.

Beatrice White

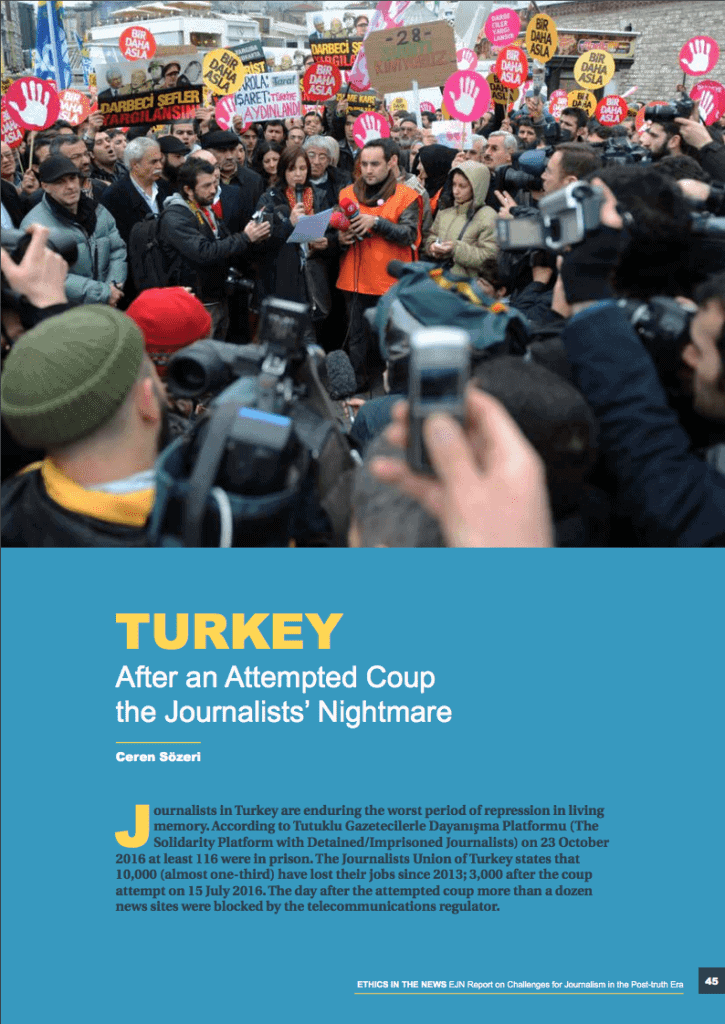

Snap elections called in Turkey are set to take place on June 24 against a backdrop of turmoil, conflict and crises, and amid a continued clampdown on freedom of expression and civil liberties. Fake news, political interference, and conflicts of interest have eroded public trust in the country’s media and reinforced the sense that coming elections are unlikely to be free or fair.

In March, press freedom in Turkey was dealt yet another blow when it was announced that the Doğan media group would be sold to Demirören Holding. The group, which includes the country’s most widely circulated newspaper, Hürriyet, and broadcaster CNNTurk, had been one of the few remaining independent actors in Turkey’s mainstream media landscape. Critics of the government saw the move as heralding the end of pluralism for Turkey’s media. With sweeping arrests of journalists and closures of outlets deemed too critical of the government, media freedom has been under sustained attack for some time now. The sale of Doğan means that 80-90 per cent of Turkey’s media is now under the government’s control. Out of 10 of the most read daily newspapers, nine are now owned by groups and individuals close to the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) party and often to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself. The figure is the same for the country’s most watched TV channels.

A majority of the pro-government firms who own media in Turkey are also involved in other sectors such as construction, energy and mining. Favourable coverage of the government has long been used as a shortcut to commercial advantage by the bosses running these conglomerates, with scant regard for media ethics. The Doğan group’s coverage had been regarded as mildly critical of the AKP government, through recently, in the wake of the repressive measures and purges that followed the attempted coup in July 2016, this had been toned down significantly. Yet its reporting was still not satisfactory for Erdoğan, whose tolerance of dissenting voices in the public sphere has continued to diminish. “Editorial independence [in Turkey] has never existed,” admits Faruk BildiricI, the ombudsman for Hürriyet. “Now it has become worse. Journalism has become too caught up with the centres of political and economic power.” The worsening state of the media of course has serious implications for the country’s democracy.

Under a cloud of distrust

President Erdoğan recently announced snap elections would take place in June, bringing the vote forward by almost a year from spring 2019. These elections will take place at a time when public trust in the media has sunk to a real low. Yet on this, as in in so many areas of Turkish public life, there is no consensus across the country. The 2017 digital news report of the Reuters Institute found that the proportion of those who trusted and distrusted news media and Turkey were remarkably evenly matched. 40 per cent of respondents said they trusted news overall, while 38 per cent distrusted it. “This is an indicator of a very polarised society and news media in the country,” the report said. Another striking finding was that both interest in the news and avoidance of the news were very high. These seemingly contradictory trends highlight the contrasts in perceptions and experiences that exist in Turkey.

A report based on opinion polls from the Centre for American Progress published earlier this year also found sharp polarisation and divisions, particularly on the management of the coup and Erdoğan’s leadership. The report, which polled voters from across the political spectrum, argued that a new Turkish nationalism is taking shape – characterised by religiosity, isolationism, and scepticism towards the outside world and ‘global elites’. The survey identified high levels of mistrust of the media and the government but also of the outside world, particularly the West and the United States. The level of education was identified as a key divider in Turkish society and strongly determined the measure of nationalist sentiment among respondents, with more highly educated Turks likely to be more critical of the government and less suspicious of the outside world, though still often retaining a broadly nationalist outlook present across the board.

Taking on fake news

One group trying to combat this mistrust are the team behind fact-checking website Teyit. Set up in 2016, the site aims to verify the most viral and sensitive claims doing the rounds. The war in Syria, atrocities against the Rohingya in Myanmar, and violence in the mainly Kurdish areas in the south-east of the country have been some of the recent crises around which wild fake news claims have been circulated, both on social media and within the mainstream media. The deployment of Turkish troops to Afrin in northern Syria at the start of this year, in a bid to prevent the establishing of any autonomous Kurdish region on the country’s border, known as ‘Operation Olive Branch’, provided ample material for the fact-checkers. They collated a round-up of some of the most outlandish and widely disseminated examples of fake news. These included a video broadcast by a number of mainstream media channels (including Hürriyet) allegedly showing military operations in Afrin but that was revealed to be footage of a Russian military drill held in September 2012. Another video from Afrin, published on national news sites such as Milliyet and TV channels such as Habertürk, was identified as a sequence from the video game Medal of Honor.

As elsewhere, the global soul-searching around the proliferation of fake news and its very real consequences has had unexpected repercussions in Turkey. In furious broadsides reminiscent of Trump’s attacks against well-established US media, Erdogan railed against the ‘fake news’ disseminated by the US and Western countries about Operation Olive Branch. The pro-government media, such as the new, slick English-language news channel TRT World, Anadolu Agency, and Sabah have all rallied to denounce fake news in connection to Afrin – but being careful to limit their investigations to content supportive of the Kurdish Syrian forces or otherwise critical of Turkey. In an surreal situation, the pro-government media disseminate false or misleading information when it supports the government’s narrative, but simultaneously claim to lead the fight against fake news by taking a flagrantly partisan approach to rooting out false claims from the other side.

While these efforts, even if one-sided, could be construed as somehow useful in that they do successfully verify and debunk disinformation that is being circulated, Gülin Çavuş, an editor at Teyit, is less than enthusiastic about such contributions to the battle against fake news. “If you are fact-checking you have to be transparent and non-partisan – to show both sides of coin and not take sides,” she argues. “Partisan people can fact-check something specific but cannot be fact-checkers. The government and TV channels use fact-checking for their own ends,” Çavuş says. This is also why, in her view, the citizen journalists who often step in to cover stories ignored or misreported by the mainstream media are no panacea. Many images and reports circulated by ordinary citizens or engaged protesters during the Gezi protests in 2013, for example, contained factual inaccuracies or exaggerated claims.

‘Patriotic Journalism’

Turkey continuing state of emergency, declared after the coup in 2016, has been used to justify a raft of undemocratic measures, including mass arrests, purges, and steps to severely limit to freedom of expression. Unsurprisingly, this means the current political atmosphere in the country is one of dread and fear. The space for pluralism in Turkey’s media is increasingly narrow, and the government’s efforts to twist the situation so that any criticism is regarded as bias has been successfully supported by sympathetic media bosses. As a result, media parrot the government’s discourse, even using turns of phrase and words simply lifted from government press releases. Recurring boilerplate terms such as ‘neutralising terrorists’ to describe the killings of insurgents, or ‘Gülenist Terror Organisation’ (or ‘FETÖ’) to label anyone purged or arrested for their associations with the movement, are ubiquitous in the news. It has gone so far that failure to adopt this language is liable to raise suspicions and has been used as grounds for accusations of treachery or support for terror organisations.

Around the time Turkey invaded Afrin, Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım summoned news editors from the main media outlets to a meeting during which he issued a series of ‘recommendations’ on how to cover the military operations in a ‘patriotic’ manner. These included the injunction to “take account of national interests when quoting international news sources critical of Turkey” – a euphemistic warning that coverage critical of the war would not be seen kindly. This attitude is consistent with the Turkish authorities’ tendency to equate information concerning politically sensitive topics (most notably the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK) with active support for the actors involved. Academics, journalists, and writers researching this subject have often come under suspicion or been jailed for alleged terrorist sympathies. The evocation of national security to encourage favourable coverage of the war was perhaps not surprising, but the resulting fake news storm demonstrates that many in the media see it as safer to print lies that support the government narrative, rather than facts that might contravene it.

Injunctions of this type have led to a climate of suspicion that has crept into almost all areas of public life. As a result, people feel compelled to bring up support for the country’s ‘martyrs’ (the term used for soldiers killed in combat) even in non-political contexts and spaces, such as at cultural sporting events. The pervasiveness of this climate is illustrated by another bizarre case in which a group of school children were prevented from staging a play as it was deemed to contain ‘anti-war’ messages inappropriate at such a ‘sensitive time’ for the nation. This starkly illustrates why fact-checking in Turkey, even when it strives to be strictly apolitical, is far from a safe or straightforward exercise.

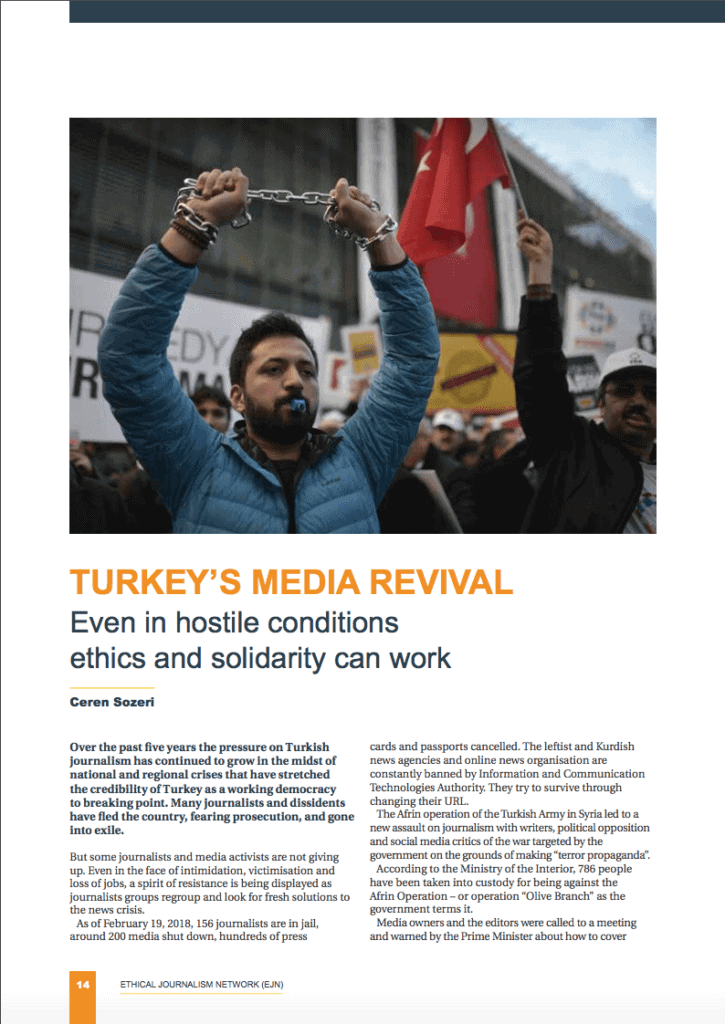

Journalism under siege

The deterioration in the quality of Turkey’s media is due, according to Çavuş, to a lack of training and competence among journalists, and to an economic model that is primarily interested in profit and clicks, putting journalists under both political and financial pressure. “Quality is the most critical thing – journalists don’t know where to take information from or how to check it,” she explains. Teyit, along with other independent platforms such as P24, regard better training as key to improving and strengthening Turkish journalism, alongside media literacy initiatives targeted at the public.

Bildirici retains a somewhat hopeful view, despite being keenly aware of the challenges: “Confidence in the media has decreased to a very low level. But still, people are making an effort to find trustworthy information. Despite everything, the media remains the main source of information for people. It will continue to be so.” From its current embattled state, however, Turkish media faces an uphill challenge to win back credibility and public trust. With a critical mass of the media now effectively under government control, and with the prevailing atmosphere of fear leading even the most principled journalists and editors to engage in self-censorship, it is difficult to be optimistic about whether Turkey’s media can provide the space for public debate so crucial to meaningful democratic processes. As well as its tendency to report the government’s rhetoric uncritically, media in Turkey often publish incendiary commentary bordering on hate speech, aggravating tensions against vulnerable groups such as minorities and refugees and further polarising the country.

The extent of the ʽcapture’ of media by governments is reaching alarming levels across Europe. Independent media are undermined if not attacked outright, whereas outlets serving as vehicles for governments’ narratives are bolstered by subsidies. In the case of Turkey, total compliance is a requirement not only for economic reward, but simply to survive, as the fall of the Dogan Group demonstrates. In this context, transnational alliances of fact-checking projects across Europe, such as the International Fact-Checking Network, could be a lifeline for independent media in countries such as Turkey, helping to provide legitimacy, as well as much-needed support and solidarity. In light of the pervasive nature of fake news and its proven capacity to distort public debate across national boundaries, reinforcing such networks would be a wise move for European policy-makers looking to protect democratic debate both at home and abroad. For EU countries seeking to preserve media pluralism, Turkey should serve as a cautionary tale. As the Turkish writer Ece Temelkuran warned in a prophetic piece: “We thought our own tool, the ability to question and establish truth, would be adequate to keep the discourse safe. It wasn’t.”

This article was republished with permission of the Green European Journal. You can read the original here.

Read more about the EJN’s coverage of press freedom and media ethics in Turkey here.