‘There Comes a Time’…..

By Salim Amin, Chairman of Camerapix and Board member of the EJN

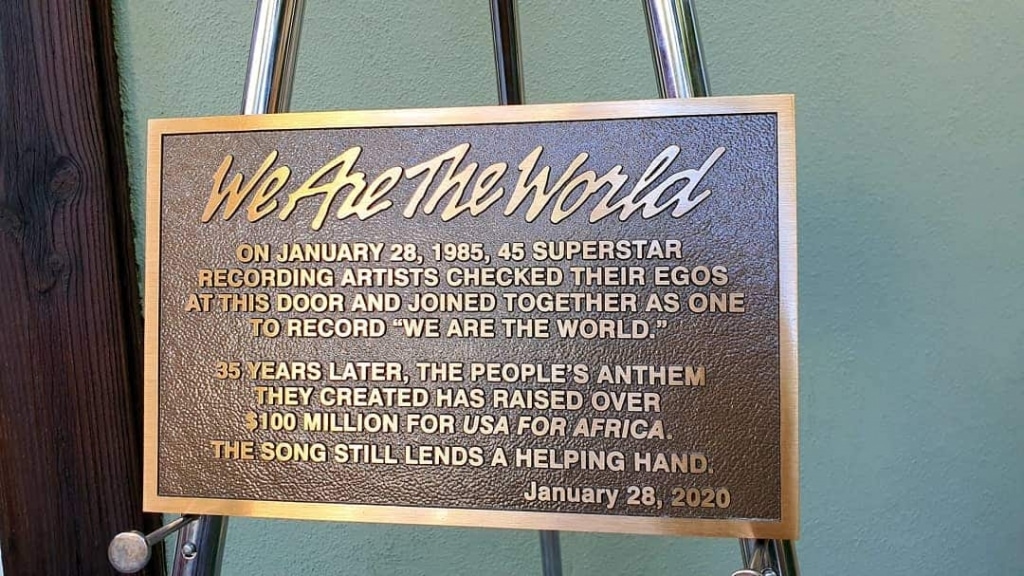

On January 28th, 2020 I was in Los Angeles, California at what used to be the famed A&M Studios, now the Henson Studios, home to those most famous of all Muppets. I was looking on as a plaque was unveiled outside the massive Sound Stage One, by one of the legends of music Dionne Warwick.

The plaque read:

“On January 28, 1985, 45 superstar recording artists checked their egos at this door and joined together as one to record “We Are The World”. 35 years later, the people’s anthem they created has raised over $100 million for USA for Africa. The song still lends a helping hand.”

$100 million … that is a staggering sum of money, even today. In the 1980s it was a colossal amount.

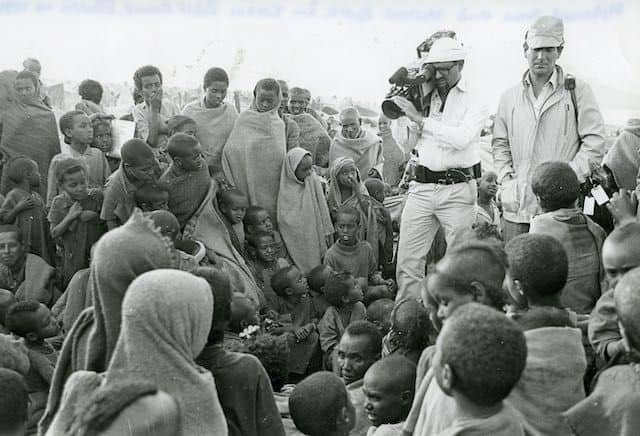

And all this came about because an African photojournalist, together with his three colleagues, decided he would not be deterred by a civil war, a government bureaucracy, or a logistical nightmare, to tell the story of a “biblical famine” that could have killed over five million people in Northern Ethiopia, but in the end claimed over a million lives.

This is the power of journalism. Good, ethical, transparent journalism. This is what most journalists set out to do … to make a difference, to save lives, to tell stories that can change people, can change a world.

But this is not how journalism is today.

That African photojournalist was Mohamed Amin, my father. His images from Northern Ethiopia were seen by over 1.5 Billion people … that’s “Billion” with a “B”! And this was in 1984/1985 when there was no internet or social media! I would be hard pressed to imagine that even a tenth of that number of people would see that story today despite the access that people have to information.

For starters, a story of starving people in Africa is so “last century” … it holds little appeal to an increasingly jaded audience. Competing with reality TV like the Kardashians, sport, music, entertainment that young people can customize to their tastes, means a story like the Ethiopian Famine would not even be on the “playlist”.

On a more positive note, stories coming out of Africa today are showcasing a vibrant, innovative, culturally-rich Continent that is no longer the stereotypical “Dark Continent” that it has been labelled for so long. This is in large part down to the internet and social media …and not because of good journalism! Young people especially around the world are consuming their content via social media platforms and Africans are sharing their stories on these same platforms. International media still mainly focuses on the doom and gloom from Africa – corruption, failed elections, attempted coups, disease – these are the subjects that still make international headlines; but much fewer people are following international media headlines now …

Young Africans have started changing the narrative of their own Continent. They are telling their stories and the story of their countries and lives as they see them. They are not pulling punches either. They tell the good and the bad. But what many young journalists on the Continent lack is some of the training to be able to tell high-quality stories in an ethical and objective way, as well as that truly global audience that could bring them hundreds of millions of viewers. They are fighting to compete with “entertainment” but they are adapting very fast to tell their stories in a more appealing way. There has been a vast increase in sitcoms, dramas, platform series, films and documentaries coming out of Africa. They are populating platforms like Netflix and also local online VOD channels. The production quality and, more importantly, the storytelling is able to compete with international productions.

The lack of resources available to African journalists to tell news stories is however another challenge, as are the very harsh working conditions in many countries across the Continent where people in power see media practitioners as “public enemies”, censoring them or forcing them to self-censor for fear of deadly reprisals. Again, social media and online access have helped stories come out of countries where both local and international media are not allowed to freely operate … citizens have become “journalists” and have reported revolutions and unrest using their social media platforms. But we have to be able to give context and analysis and background to the social media “bursts” of information and this is where African journalists still are being challenged. The analysis and context to many of these stories like the Arab Spring, the revolution in Sudan that ousted Omar Al Bashir, are still coming from international media outlets as opposed to African media houses. What is refreshing is that many of the international media organisations now employ African correspondents to give this context.

Ethiopia, like media, has transformed over the past 35 years. It is now one of the fastest growing economies in the world, a country of enormous opportunity, a place where drought does not necessarily equal famine, where lessons have been learnt and safety nets put in place since 1984. There are dozens of local TV stations that have launched over the last couple of years, over 150 media licenses have been issued, and Ethiopian journalists are telling their own stories, making their own movies, celebrating their own culture in their own language.

But without that reporting from 1984 perhaps we, outside of Ethiopia, would still be telling the same story …

Photo credits:

- Image 1: Plaque unveiled to commemorate 35 years since the recording of ‘We Are The World’;

- Image 2: Mo Amin and Michael Buerk at Korem Relief Camp, Ethiopia, 1984, source: Camerapix