Photojournalism is about humanising problems, not sensationalising them

Megan Howe

“When I was a teenager I didn’t even know what a refugee was-then I became one.”

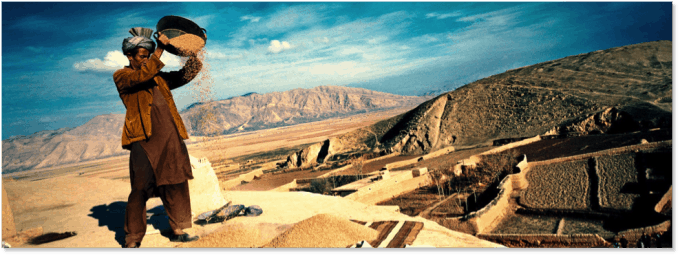

Zalmaï spent his childhood in Afghanistan but was forced to flee at 15 after the Soviet invasion in 1980. He and his older brother fled with the help of a smuggler through the rural mountain terrain, evading Soviet troops before finally reaching the Afghan-Pakistani border. There he sought refuge and later travelled to Switzerland where he made his home in Lausanne. He studied photography and started photographing refugees in 1989 to help deepen the understanding of their stories.

“I don’t work to please my colleagues and have my name in the New York Times. It’s about humanising problems, not sensationalising them.”

Zalmaï repeatedly traveled to Afghanistan to document the refugee situation. During the Soviet invasion, over 6 million Afghans fled the country as refugees. But between 1988 and 2000 nearly 5 million refugees retuned to Afghanistan. Many of the returnees faced continued hardship upon their return as the Taliban took power.

After 2001, a horde of foreign photographers and journalists flooded into Afghanistan to cover the US invasion and the war against the Taliban.

Zalmaï says that “many journalists had no idea what was happening in the country. They just came to be embedded with foreign troops. I told them this was not the way to cover the story of Afghanistan-you can’t just tell the story of the soldiers.”

Zalmaï said he faced an even greater risk than foreign journalists in his attempts to show the human side of the conflict. If captured, he would have been seen as a traitor in the eyes of the Taliban and likely have been treated worse than an international correspondent. Although Zalmaï did embed with NATO troops on a few occasions he was more interested in telling the stories of his countrymen.

After photographing for various international publications, Zalmaï started work with Human Rights Watch last year where, without the pressure to sell magazine and deliver what his editors demanded, he says he has more freedom to tell the real story.

“Its not about politics, not about misery, not about who is better or who is worse, who has war and who doesn’t. No. We are all humans. We have to make a connection between East and West, and I feel like I am a bridge. ”

Zalmaï says that his Instagram account allows him to “go directly to my audience without censorship” or having to negotiate with picture editors.

Ethical coverage of the refugee crisis

Ethical coverage of the refugee crisis

Many journalists feel intense pressure to cover conflicts or stories in a certain way to meet the “market demand.” Zalmaï says that journalists and photographers must have an extraordinarily strong conviction because they will always be pressure to create a product that appeals to the masses.

“I don’t want to be part of the propaganda. Photographing people in crisis is not a Hollywood movie. We must understand these are real people, with real suffering, in a real situation. Our job is to be as human as possible.”

After a recent trip to Lesbos, Zalmaï said that many of the photographers waited to capture the most dramatic shots possible. He said the island has become a ‘must-see’ for media, effectively driving journalistic or humanitarian ‘tourism.’

“They [other photographers] wanted lots of waves. They were also disappointed on day that was sunny because they thought that would lead to less dramatic shots.”

He says after the boats arrived, the photographers would rush to shoot the boats coming up to shore and then back off. “They didn’t even talk to the people.”

“I try to be honest and simple. Making a beautifully sad picture simple is difficult. Making a dramatic picture is very easy.”

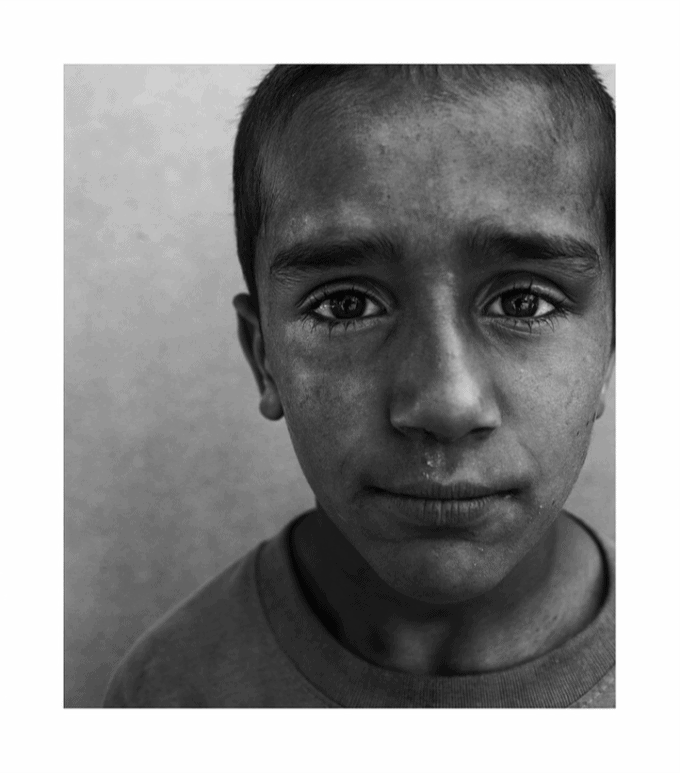

With global displacement at an all-time high of almost 60 million, Zalmaï says the media should avoid instilling fear in their audience. “Regarding this crisis in Europe, we need to humanise it. Numbers scare people. When you give a face to the number, people feel closer to the situation.”

Last year Zalmaï published ‘Dread and Dreams‘ a book of photos compiled from 2008 to 2013 about the war in Afghanistan. Staying true to his convictions, only one dead body appears in the book. Instead of highlighting gore and glory, he tells the story of the people experiencing war within Afghanistan.

His final piece of advice to the next generation of photojournalists:

“Try to understand your subject, listen, and be close to the people. Don’t be a vulture taking what you need and leaving. Give back. These people don’t have anything. They only thing they have left is dignity and humanity, don’t take that from them too.”

Zalmaï was talking to the EJN at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival event, Desperate Journeys.

(All photographs from zalmai.com and instagram.com/zalmai)

For more on the ethics of how media cover migration read our Moving Stories report which covers 14 countries and the European Union.