Outrage, polls and bias: 2019 federal election showed Australian media need better regulation

Denis Muller, University of Melbourne

Two big media-related issues have emerged from the federal election: how opinion polls are reported and the polarisation of the main newspaper groups.

Opinion polls have been part of Australia’s political landscape for 90 years, and for most of that time they have been reliable barometers of public opinion.

As a result, they have acquired considerable credibility. Malcolm Turnbull weaponised this for political purposes when he justified his challenge to Tony Abbott’s prime ministership in 2015 on the basis that Abbott had lost 30 consecutive Newspolls.

It was a gross lapse of judgment.

Not only did it set up Turnbull to be judged by the same criterion – as duly happened last year when he lost his 31st Newspoll – but he chose precisely the wrong time to elevate public opinion polls to the status of prime ministerial kingmaker.

Read more:

Coalition wins election but Abbott loses Warringah, plus how the polls got it so wrong

Public opinion polls have been living on borrowed time since mobile phones began to displace household fixed-line phones, a gradual but inexorable process over a couple of decades.

Without digressing too far into the complexities of sampling, it is now difficult, time-consuming and expensive to generate a genuinely random sample of voters.

Telephone polling, introduced in the 1980s, originally drew its samples from the Telstra list of fixed-line numbers – in other words, from the White Pages. There is no equivalent available list of mobile phones so, for practical purposes, drawing a genuine random sample has become impossible.

To cope with these realities, polling organisations have adopted somewhat makeshift sampling and interviewing procedures, drawing on various combinations of fixed-line phones, mobile phones, large panels of available respondents, and robo-polling.

This in turn raises questions about the validity of statements about sampling error, something the election results brought home with a thump.

Yet the media have carried on reporting the polls as if nothing has changed.

Poll results still make banner headlines. Stories are still written on the basis that the data are as good as they have always been.

The public, accustomed to the longstanding reliability of Australian polls, do not know and are not told that this is nonsense.

Polls are useful and interesting stories, but the reporting of them needs to change.

There needs to be greater transparency about how a poll’s sampling and interviewing are done. The way a poll is done – whether it is a human being or a machine asking the questions, for instance – is significant.

The public is also entitled to know that today’s polls have limitations that polls of the past did not have. They are more indicative and less precise, so statements about sampling error need to be qualified accordingly.

And as the main newspapers have become more partisan, so the reporting of polls has shifted from straightforward accounts of the data to stories dominated by analysis, comment or wishful thinking on the part of the writer or the editor.

Partisanship in the media, especially the newspapers, has always been with us, but analyses by Media Watch and The New Daily show it reached extreme levels in this election.

Read more:

Mounting evidence the tide is turning on News Corp, and its owner

An audit of metropolitan newspaper front pages by Media Watch showed a heavy anti-Labor bias by News Corp papers, and a roughly equivalent – but less strident – pro-Labor bias by the old Fairfax (now Nine) newspapers, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age.

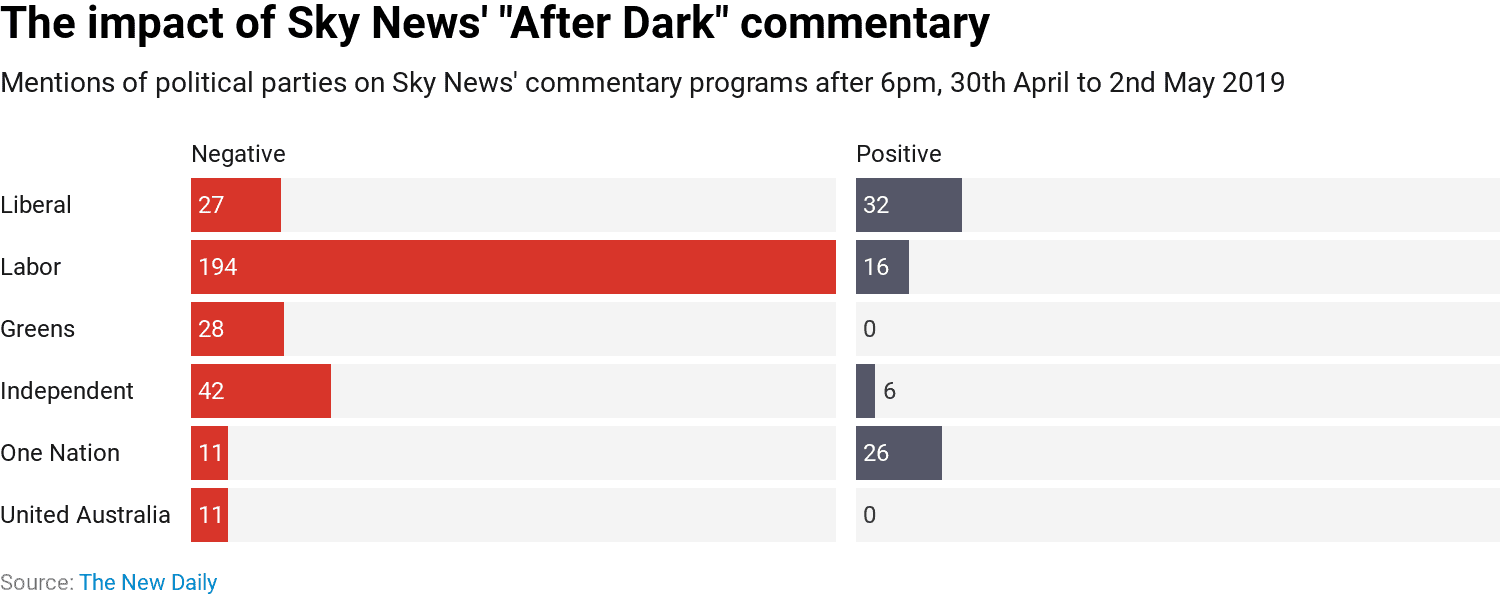

The New Daily analysed three nights of Sky News coverage – April 30, May 1 and 2 – and found gross anti-Labor bias:

The New Daily, CC BY-ND

The New Daily, CC BY-ND

News Corp’s unconstrained anti-Labor bias cannot account entirely for Labor’s disastrous showing, but common sense says it accounts for some.

For example, the company has a daily newspaper monopoly in Brisbane through The Courier-Mail. It was virulently anti-Labor and Labor did astonishingly badly in Queensland. Coincidence? Possibly, but unlikely.

If Australia had a half-decent system of media accountability, there would be a public inquiry into the increasing polarisation of Australian newspapers and into the conduct of Sky at night.

However, the newspaper industry’s self-regulator, the Australian Press Council, relies on the two big newspaper organisations for nearly all its funding, so the chances of having such an inquiry approach zero.

And the broadcasting regulator, the Australian Media and Communications Authority, has never shown the slightest interest in reviewing the way commercial television and radio cover elections.

So in an age where polarisation is undermining democracies around the world, Australia is stuck with an increasingly polarised media, a highly concentrated media ownership landscape and no apparent way to do anything about it.

Denis Muller, Senior Research Fellow in the Centre for Advancing Journalism, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main image by Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND