Journalism and the challenge of hate spin

Tom Law

The role of some media in the rise of Donald Trump and the fears that his rhetoric, by bringing fringe far-right and fascist voices to into mainstream discourse, is symptomatic of wider a trend that media have to grapple with hate spin.

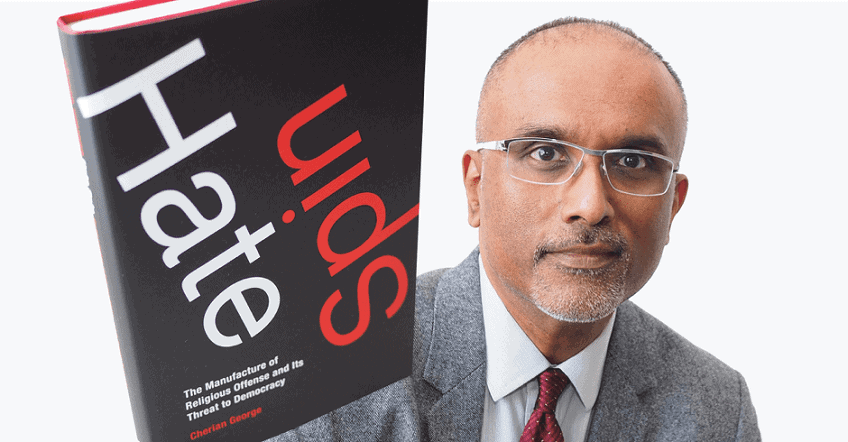

Populist leaders like Trump are normally too smart to engage in direct hate speech or in calls to action against minorities, says free speech academic Cherian George. Speaking at the launch of his new book, Hate Spin, in London last week, George said that traditional legal definitions of hate speech lack the nuance to understand how expert propagandists operate.

The law, he said, is unable look at hate speech in a holistic way to consider how the new authoritarians – such as Orban in Hungary, Putin in Russia, or Erdogan in Turkey – contribute to a growing climate of intolerance through sustained dog-whistle politics and create space for voices that more overtly incite violence, xenophobia and discrimination.

The EJN’s five-point test provides a framework for journalists to identify hate speech but when it is applied, it is largely Trump’s supporters, rather than the President-elect himself that most obviously stray from what might be considered merely loose and offensive, to the dangerous language that is partly responsible for the rise in hate crime in the United States since the election.

Hate Spin

Hate Spin, investigates and compares the manufacture of mass righteous indignation against minority groups in India, Indonesia and the US. George identifies a trend of self-styled religious leaders actively seeking the occasion to take offense in order to provide justification for the incitement of discriminative violence against targeted groups.

This is, George says, a double-sided strategy of political contention, exploiting identity politics to mobilise supporters in what can at first appear to be a spontaneous explosion of outrage but is in fact part of a political strategy.

What seems to be an authentic religious reaction is actually a coordinated political propaganda effort to stoke tensions and raise the profile of those involved. Journalists, George argues, need to take incidents of hate propaganda more critically and not take protests at face value.

“Take pride in uncovering the reasons behind hate campaigns” he urges journalists. If we treat politicians’ speech with inbuilt scepticism, why not treat the claims of self-proclaimed community representatives with the same analytical approach. Too often the attitude of news media to protests over religious sensitivities is “here go the Muslims again”, according to George.

Indonesia is a good example of this where short news reports recently claimed that “Muslims [are] outraged by alleged blasphemy of governor”.

“Most of the lay public were satisfied with an explanation as it fits into a wider narrative of Muslims losing their heads over a perceived offence,” he said. “I would argue that if it is prolonged it is not spontaneous.”

The individuals taking part in the protests may feel genuine anger. But George argues that “we need to scratch the surface” to expose the political entrepreneurs using this outrage to gain prominence and influence.

Insult laws often backfire, he told the audience at the University of Westminster, as they as incentivise offence taking by “hate spin agents” who are the least tolerant members of society and are only too happy to protect themselves from the slightest offence when the obvious response would be to look away.

The President of Indonesia cannot turn to Muslim hardliners and tell them they are overreacting, as that would be seized upon as evidence of insensitivity. Hardliners are all too aware of this, which means that “moderates are caught in a bind.”

Hate Spin considers whether analysis of the phenomenon focuses too much on speech and not enough on actions in a comparison with Muslims in Tennessee in the US and Christians in West Java, Indonesia.

Both communities wanted to build larger places of worship, both came under attack by larger majorities. In Tennessee, the Muslim minority were described as terrorists connected to the Muslim Brotherhood who wanted to impose Sharia Law on the wider community. False and outrageous claims that nonetheless gained traction.

In Java, the wish to build a place of worship for a small community was spun into an attempt to Christianise the whole of the world’s most populous Muslim country. This and other vicious false rumours stopped the church from being built.

While the Murfreesboro Centre in Tennessee now exists, in Java the churchgoers are still operating out of their homes and worshipping as a means of protest outside the President’s house.

In theory, Indonesia has more protection against hate speech compared to the US. Muslims in Tennessee had no recourse to the hate speech they suffered but while the US “takes a liberal view on speech they take a high view on religious equality so the Supreme Court was always going to stand up for their theological rights” George said. In Indonesia Christians cannot rely on the courts as, regardless of their decision, neither local nor the national government has the moral courage to implement a verdict in their favour.

Too often the state, law enforcement or courts may intervene to protect people from insult but don’t step up when people really need it, Hate Spin concludes. “Looking at speech is not enough, we should also look at anti-discrimination laws,” says George who relates a recent event he attended in Malaysia organised by an interfaith NGO that was shut down by a mob. “Instead of telling the mob to go away, they told the organisation to stop. It didn’t make sense at so many levels.

“Then you realise that this is happening all over the place partly for practical reasons, if the police are outnumbered and under-resourced, the solution is to take the side which side is bigger. This is very worrying for free speech.”

The book also explores how the Hindu-right, led by India‘s President Nahendra Modi, has copied the tactic of claiming offense on a wide scale from the Muslim-right.

However, George rejects the school of thought that intolerance is confined to religion. He urges journalists to recognise that religious violence is often connected to political and civil violence more widely, giving the attacks on communist thought in Indonesia as one example.

“Extreme statements will always get more headlines than what moderates say,” he says, noting that when 100 Imams got together and made a YouTube video condemning ISIS it hardly made the headlines, even though media constantly complain that Muslims are not speaking out against extremism.