Francesca Marchese

9th April 2018

They are not racist. But they are disappointed and – more important – they are frightened. Italians voted in national elections in March 2018 and delivered a shock result with dramatic increases in the number of votes for political populists such as the Five Star Movement (Movimento Cinque Stelle) and far-right party The League (La Lega).

Media commentators were examining the role played by journalism and social networks in an election that, like the British referendum on Brexit, delivered a fresh setback for the European Union.

The elections winners are vocal critics of the European Union and the success of their populist and anti-establishment message has turned politics upside-down.

A very uncertain time for the country is now ahead. And the uncertainty extends to the influence of media in a country where the non-traditional voices of social media and online information exercise more influence than ever.

What was the role of old and new media in meeting the challenge of political change? The electoral campaign did not, as previously, operate in the wide open space of invigorating public debates and demonstrations in the elegant squares and piazze of the country’s towns and cities.

Instead, traditional media found different ways to tell the election story and the non-traditional, but increasingly influential, impact of internet media was more evident than ever. So, what has happened?

Impact of TV: A focus on “fear” and “immigration”

There were no grand televised debates on this occasion: TV did not show any head-to-head encounter between the candidates. There was no grilling of party leaders by hard-talking journalists. Lots of people did not sit in front of the telly watching programmes and listening to ideas on how to change the country for the better.

Instead, they watched 403 news stories about two inter- related items of news:

First, a racially-motivated shooting in Macerata, in the Marche region (it was an attempted massacre in which an Italian gunman, a neo-Nazi and former Lega candidate, injured 6 Nigerians) and, secondly, the brutal killing of a white Italian girl a couple of days earlier (her dismembered body was found in two suitcases: three Nigerian migrants are arrested and another one is currently under investigation).

The “Carta di Roma” association, which promotes and seeks to implement the Journalist’s Code of Conduct on immigration, said the two stories were reported twice on television news programmes over a month according to researchers at the independent Osservatorio di Pavia.

It was not the only case study. During 2017, according to the media report Notizie da paura by Carta di Roma, television news programme in prime time, broadcast an extra 26 percent news about immigration than in 2016.

The report found that

- Coverage focused on the actions of NGOs, sea rescues, legal issues and crime stories.

- Media reporting deals with migration in such a way that it risks being presented as a permanent emergency, rather than a social reality that needs to be addressed in a coherent and rational manner.

- Discrimination is found in reporting of related issues dealing with religion, violence, financial and health problems. And migrants, themselves, are usually given little voice, and are present in only 0,5 percent of media stories.

The report found that in this pre-electoral year news reporting with a sensationalist tone increased and the political agenda has had a strong impact in the way news stories are connected.

The result of all of this according to the authors has been “a cocktail of insecurity and fear.” It hardly surprising to find that the sense of threat towards migrants and refugees has increased in Italy: from 33 percent in 2015 to 43 percent in 2017, according Demos&Pi, a research organisation based in Vicenza.

And it is not just news reporting that is criticized. Infotainment provided by some popular Italian talk shows and political programmes are also under fire.

One, “Dalla Vostra Parte” (broadcast by Mediaset, Rete 4) sparked particular outrage and has been accused of open racism. One of its reporters was red because, it is alleged, he paid a migrant to impersonate a Roma crook and an extremist Muslim on two separate occasions. Nevertheless, the programme is so popular it has spawned two different satirical versions.

Newspapers: the word “fear” in the news

According to Audipress data (28th February 2018), 32 percent of Italians read a newspaper every day. Those who read the papers during the last two months of the electoral campaign were exposed to the repetition of the word “paura” (“fear”) 334 times.

During the final month of the election campaign the most common words in headlines linked to the Macerata story were “Salvini” (the name of the candidate of the Northern League), “immigration”, “immigrant”, “hate”, “racism” and “stranger”. In the election Matteo Salvini gained 18 percent of votes, surpassing even Silvio Berlusconi.

Carta di Roma says: “In the press, the facts of Macerata story are closely connected with politics: from the beginning of February they enter into the agenda of the election campaign and dominate it. Words such as rage, hate, fear and fault appear several times, associated with increasing sensationalism.”

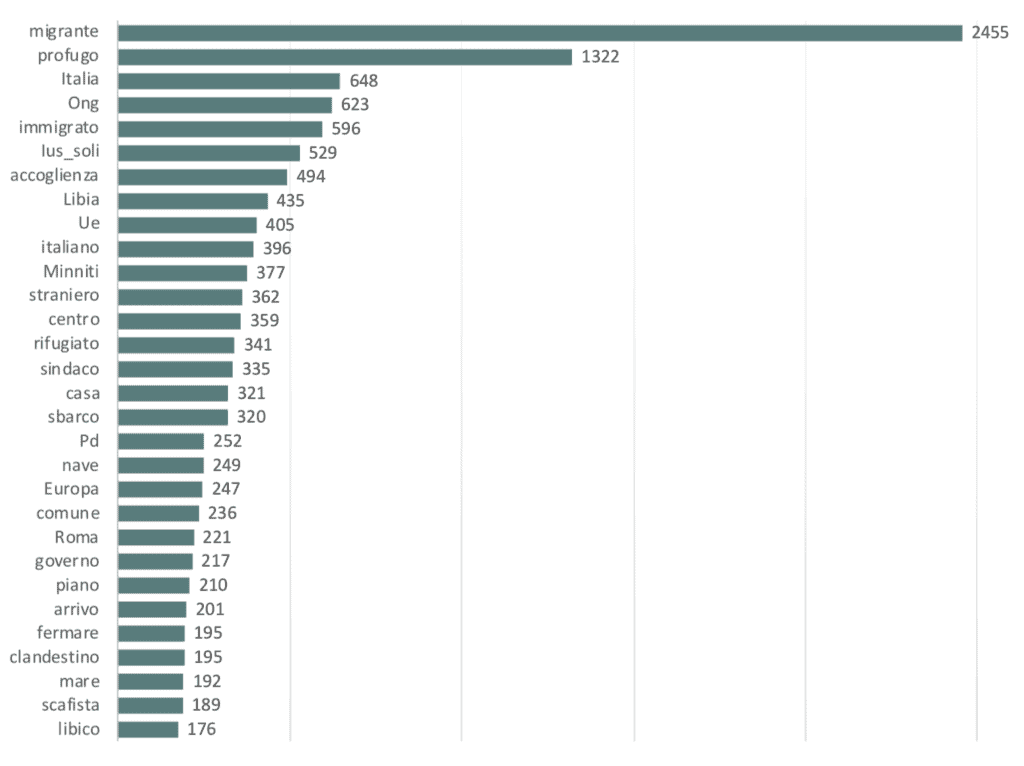

Looking back over 2017, the report says the word “migrant” appeared 2,455 times in headlines on the front pages of daily newspapers.

National press such as Libero, Il Tempo and La Verità have been criticised over sensationalist and intemperate headlines. In 2015 Libero, for instance, published a headline “Islamic Bastard”: the paper faced legal action but its editor Maurizio Belpietro was cleared from any accusation because, according to the judge, no crime was intended.

More recently, the same newspaper was criticized for its headline “In order to knock down Renzi, it is necessary to shoot him” and Il Tempo published the headline “Here is the migrant’s malaria”.

But it’s not just the traditional media where problems arise. According to Filippo Trevisan, who is Assistant Professor at the American University School of Communication, this election confirmed a trend established after the election five years ago that

Italian voters are ever-more keen on alternative online information sources. Voters searching the internet for information about the Five Star Movement were more likely to look specifically for the party’s official website and online streaming channel rather than tune into the traditional media.

Trevisan says that recent studies illustrating low levels of trust in media organisations have made Italy and some other European countries vulnerable to the spread of misinformation. He highlights a Buzzfeed report at the end of 2017, which exposed popular Italian websites and Facebook pages that posed as news organisations but that were, in fact, trafficking misinformation and content with anti-immigration bias.

It’s of little surprise, then, when this type of content increased as populist leaders put immigration at the heart of the 2018 election campaign.

Trevisan also says that popular news websites controlled by the PR agency in charge of Five Star’s election campaign have posted content espousing Kremlin propaganda. The problem is, he argues, not simply that misinformation is readily available online, but also that a large proportion of Italians find this content credible.

However, Italian journalist Matteo Grandi, an internet specialist, says fake news did not play a decisive role in the election. “In my opinion it can’t be proven that the election was influenced by fake news”, he says, “Fake news is usually made for business reasons rather than for ideology”. He asks, provocatively: “What influences the results most? A fake news shared by some digital illiterates, or daily news television programmes all lined up to a party?”

For their part, Italian reporters are fighting back. Both the Italian Ordine, the professional association of journalists, and the journalists’ trade union Federazione Nazionale Stampa Italiana are calling on reporters to be more responsible.

Speaking about shocking headlines, the president of the Italian Ordine of Journalists which monitors journalist ethics Carlo Verna told the Ethical Journalism Network: “These need to be penalized. The Ordine has highlighted several cases. In the months to come, we are expecting more actions to be taken”.

In the last six years, a new law, the Severino law, has forced all Italian professional associations, including the Ordine of Journalists, to modify how they deal with rules and penalties. Now, norms are written by a National Board and disciplinary issues are handled by Discipline Boards, both local and national. “Judges” of complaints are not elected among colleagues anymore, but are nominated by each local tribunal from a list of candidates chosen by a regional Board.

This law is controversial among journalists and the Ordine has asked several times for it to be reformed, but so far without success.

Raffaele Lorusso, who is the secretary of the Federation of Italian journalists FNSI (Federazione Nazionale Stampa Italiana) admits that sensationalism plays a role in media coverage. “Provocations and “shouted” titles are part of the game”, he says. “What is absolutely unacceptable is imbalance, tones which are discrimination or defamation. A journalist has the obligation to always respect truth of facts and the dignity of people. For this reason titles or articles inciting hate, racism and sexual discrimination cannot be tolerated”.

Lorusso recognizes the crisis. He says: “In the last few months some newspapers have let themselves go with headlines that are deliberately racist or insulting towards women or immigrants.”

The FNSI supports a number of initiatives to combat hate speech and the spread of fake news, including promoting the Assisi Manifesto, written by the friars of the Sacred Convent of San Francesco, which supports responsible information, and the Venice Manifesto which deals with the correct gendered language”.

In addition, two Italian national newspapers, La Stampa and La Repubblica, are involved in a ground-breaking activity, “The Trust Project” which offers more transparent standards to readers and supports the “immune system of democracy”.

La Stampa, in particular, has an ethics code and an effective policy on moderating online comments which has been recently updated.

Nevertheless, more needs to be done to strengthen Italian journalism, particularly regarding working conditions. Some freelance reporters, for instance, get paid just 35 euro for an online article in the national press and just 5 euro on local titles. Standards are important for democracy and freedom, but so are social conditions. Journalists believe the industry needs to needs to rethink its business model.

It’s just one of the issues that have come into focus as a result of the election. The need to strengthen journalism, to make people more aware of their own responsibility, to understand how the new culture of communication works and, above all, to reinforce the role of independent public interest broadcasting are all pressing issues. But without a completely new policy approach to dealing with the threat of misinformation and propaganda it’s not just journalism that is under threat, democracy itself is at risk.

References

- http://www.primaonline.it/2018/02/28/267661/i-nuovi-dati-audipress-sulla-lettura-dei-giornali-il-32-degli-italiani-sfoglia-un-quotidiano-al-giorno- settimanali-27-mensili-24/

- https://www.cartadiroma.org/news/elezioni-a-parole/

- http://cartadiroma.waypress.eu/cgi/ImageCgi.cgi?f=20180223/LV15046.TIF&t=pdfocr

- http://www.fnsi.it/titolo-di-libero-contro-renzi-fnsi-e-istigazione-alla-violenza-e-allodio-non-diritto-di-critica

- https://www.ilpost.it/2017/09/06/le-prime-pagine-di-oggi-1729/il_tempo-193/

- https://theconversation.com/in-italy-fake-news-helps-populists-and-far-right-triumph-92271

- https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/ les/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf?utm_source=digitalnewsreport. org&utm_medium=referral

- https://www.buzzfeed.com/albertonardelli/one-of-the-biggest-alternative-media-networks-in-italy-is?utm_term=.kl8YodW2J#.fk1ZNVJlK

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/28/world/europe/italy-election-davide-casaleggio-five-star.html

- http://www.lastampa.it/2018/02/05/italia/politica/le-fake-news-rischiano-di-condizionare-il-voto-tre-italiani-su-dieci-ci-credono-8CRt10HpIVq6drx5kiButI/pagina.html

- http://www.odg.it/content/testo-unico-dei-doveri-del-giornalista-0

- http://www.lastampa.it/_stc/policy/