Do British journalists play by the rules?

Neil Thurman, City University London

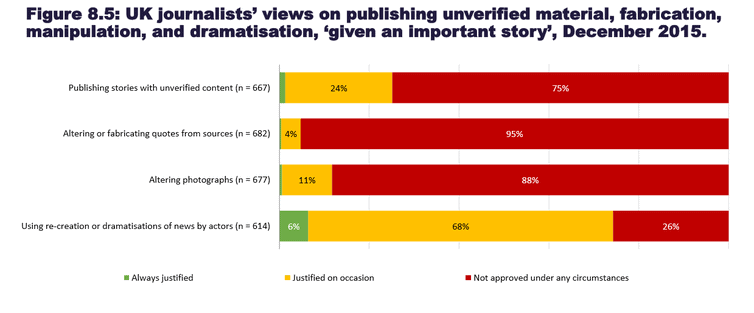

Four years after some of the more questionable practices of the UK press came to light under the scrutiny of the Leveson Inquiry, a survey of journalists has found that 25% believe it is acceptable not to verify information before publication or broadcast.

The survey, Journalists in the UK, was a detailed investigation of the working practices and conditions of UK journalists. It found that, overall, more journalists think ethical standards have strengthened than think they have weakened over the past five years.

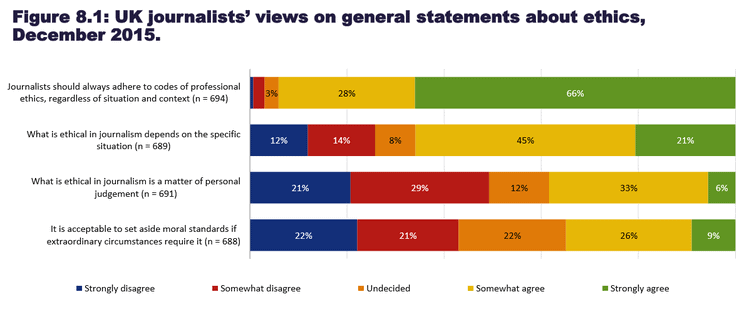

The online survey of 700 journalists asked further, general, questions on ethics, as well as questions about whether, on an important story, it is ever justified to push the boundaries of ethics and standards in several important areas. We asked journalists about whether it is ever acceptable to accept payment from or pressure sources, or to use material without permission. We also asked whether misrepresentation and subterfuge to get a story was ever acceptable and about falsification and verification.

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

It’s worth noting that, while the regulatory bodies for British journalists (including IPSO for print and online journalists and OFCOM for broadcast journalists) allow various ethical guidelines to be breached if there is a clear public interest in the story, publishing false or unverified information is never acceptable.

The overwhelming majority of journalists in the UK (94%) express agreement with the statement that they should “always adhere to codes of professional ethics regardless of situation and context”. But at the same time, two-thirds also agree that “what is ethical in journalism depends on the specific situation”. Stories in the public interest could include those that reveal criminal behaviour, protect public safety, or disclose misleading claims made by individuals or organisations.

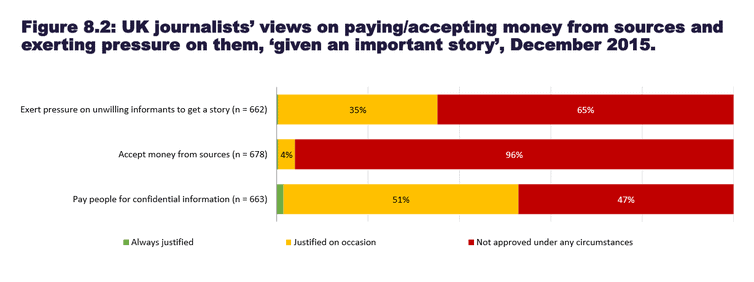

Sources: pressure or payment

Exerting pressure on unwilling informants to get a story is considered unacceptable by 65% of UK journalists, while 35% think it is justified on occasion. Clause 3 of the IPSO Editors’ Code of Practice requires journalists not to “engage in intimidation, harassment or persistent pursuit”. Specifically, they should avoid “questioning, telephoning, pursuing or photographing individuals once asked to desist”.

A survey of US journalists showed similar results, with 38% agreeing that, on occasion, it can be justified to badger unwilling informants.

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

Journalists were then asked to express their views on payments within the context of newsgathering activities. Whereas accepting money from sources is considered inexcusable by almost all journalists in the UK (96%), paying people for confidential information is considered justified on occasion by 53%. This result differs from standards in the US where only 5% of journalists believe it is justified on occasion. However, the UK professional codes clearly indicate that this is a legal practice. The Editors’ Codebook, for example, says that:

payment for stories is legitimate in a free market and it would be impossible – if not actually illegal under human rights legislation – to disallow it.

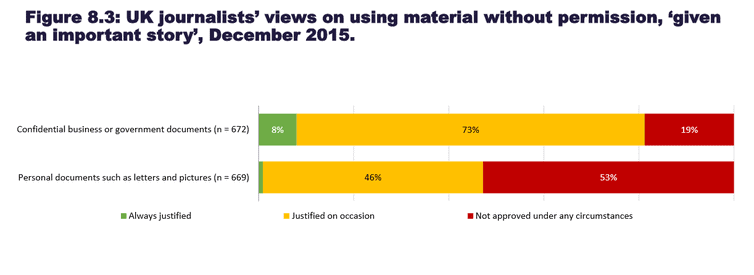

Our survey asked two questions about using material without permission. Using confidential business or government documents without authorisation is largely considered acceptable: 73% of UK journalists believe it is justified “on occasion” and 8% think that it is “always justified”.

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

In this case, UK journalists’ views differ considerably from those of their colleagues in the US where only 58% thought the use of unauthorised business or government documents was justifiable. However, Willnat and Weaver’s finding has to be seen in the context of the polarisation of opinion around national security issues in the US following the Edward Snowden and WikiLeaks cases. In 2002, the percentage of US journalists who found justification for the use of official documents without authorisation was 78%, very similar to our result.

The use of personal documents, such as letters and pictures, without permission is a different matter. Only 47% thought it was ever justified. This entitlement to respect for personal privacy applies to information and pictures published on social networking sites, whose republication is not “inherently justifiable” even if unprotected by privacy settings. However, again, exceptions can be justified in the public interest.

Although double the proportion of UK journalists say they would never use personal documents without permission as say they would never use official material in the same circumstances, their ethical stance is still relatively liberal in this area compared with some of their international colleagues. For example, only 25% of US journalists believe it is ever justifiable to use personal documents without permission.

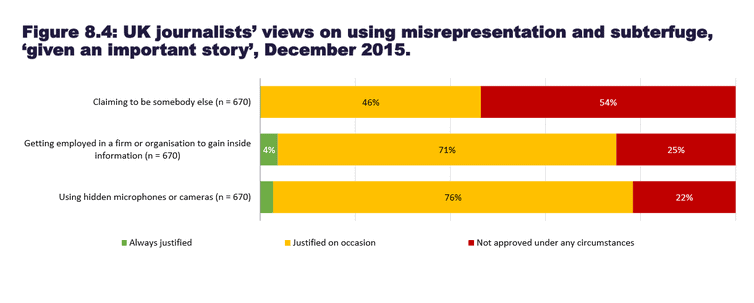

Misrepresentation and subterfuge

Should a journalist pretend to be somebody else? The relevant professional codes of practice say that misrepresentation and subterfuge:

can generally be justified only in the public interest and then only when the material cannot be obtained by other means.

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

UK journalists expressed mixed views about whether claiming to be somebody else is acceptable: 54% believe it is never justified and 46% think it is justified on occasion. US journalists are, again, more disapproving, with only 7% agreeing that misrepresentation is justifiable on occasion.

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

Reuters Institute of Journalism Research, Author provided

While UK journalists have mixed views on misrepresentation, other forms of subterfuge are accepted to a greater extent. More than 70% consider getting employed in a firm or organisation to gain inside information or using hidden microphones and cameras justified on occasion. US journalists are, again, more conservative, with only 25% believing that posing as a fake employee is ever acceptable and 47% believing the same about the use of hidden recording equipment.

Pressure to improve

We were most surprised at the relatively high proportion of journalists (25%) who believe that under some circumstances it is acceptable to fail to verify information. But when exploring working conditions we discovered how journalists, especially those working online, have an increasing workload. Perhaps this is contributing to a lowering in standards of verification?

Generally, our analysis shows some variation in views on ethics among journalists of different ranks and among journalists working in different media. Broadcast journalists exhibit wider acceptance of subterfuge and consider it more acceptable to use material without permission. Print journalists are more likely to find justification for paying people for confidential information, publishing stories with unverified content, and exerting pressures on unwilling informants.

Seniority also influences views on ethical standards. Rank and file journalists show a greater level of acceptance of practices at the ethical boundaries than managers. This finding may reflect the pressure rank and file journalists feel to “deliver the story”. Nothing perhaps illustrates this pressure better than the words of Graham Johnson, a former journalist at the News of the World who told the Leveson inquiry in 2012:

You can’t get through the day on a tabloid newspaper if you don’t lie, if you don’t deceive, if you’re not prepared to use forms of blackmail or extortion or lean on people, you know, make people’s lives a misery. You just have to deliver the story on time and on budget, and if you didn’t then you’d get told off. The News of the World culture was driven by fear.

Dr Neil Thurman is also professor of Communication at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich. This report was co-authored by Dr Alessio Cornia of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford and Dr Jessica Kunert, LMU Munich.

This article originally stated that 25% of UK journalists believed it was acceptable to either falsify or fail to verify information before publication. This was an error introduced in the production process and has been rectified.

Neil Thurman, Reader, department of journalism, City University London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Photo credit: Howard Lake, The Sun charity chief headline (Flickr: CC BY-SA 2.0)