Without empathy, journalism is lost

By Glen Scanlon

On March 15, 2019 it took a gunman just 21 minutes to kill 50 people at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

The attack was in the same city where eight years before 185 people were killed, several thousand injured and immense destruction caused by a shallow magnitude 6.3 earthquake.

About 180km north in 2016, another quake, this time magnitude 7.8, struck Kaikoura, sending shockwaves across New Zealand’s North and South Islands.

In December 2019 a volcano erupted on White Island, killing 21 and leaving dozens terribly injured.

Now, like the rest of the world, we are confronting Covid-19 – the biggest news event since World War II.

It’s very easy to feel disaster reporting fatigue – to throw your hands up, think why the bloody hell now and where do we start?

Lessons already learned are a good place. For me the biggest leadership ones to date were from the Christchurch mosque attacks.

At the time, I was the head of news and digital at the country’s publicly-funded media outlet – Radio New Zealand (RNZ). I’d been there a tick over four years and we’d been busy not just with news coverage and digital developments but difficult structural change too. We are small on a world scale; I had about 160 staff in my teams and 290 in total across the business at the time. Our Christchurch bureau office had only 8 staff.

New Zealand is, aside from the well-known seismic risks, a generally peaceful country that had virtually been untroubled by the extremist ideology and brutal violence seen in the Christchurch attack. The shock was immediate and immense.

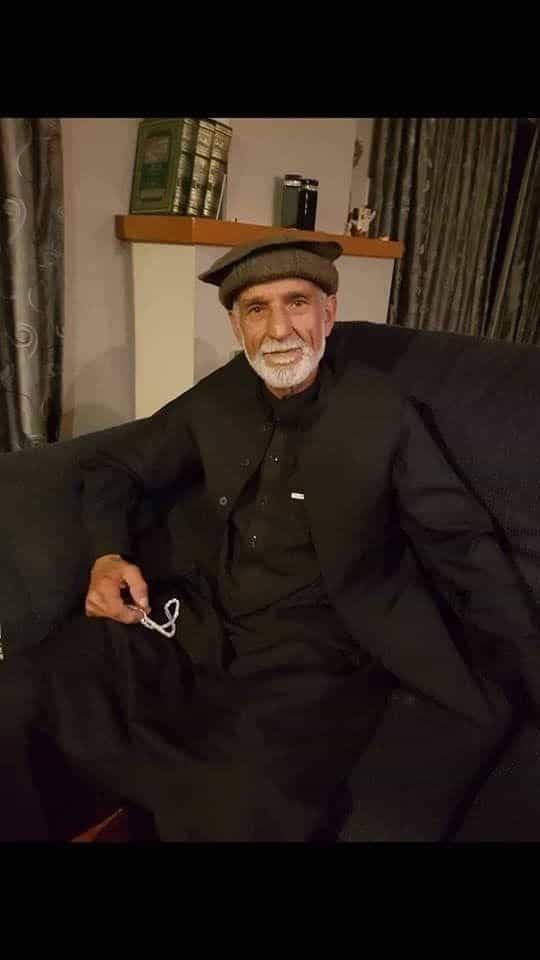

On the day of the attacks our Christchurch bureau was winding down for the week when the gunman fired his first shot killing Haji-Douad Nabi, who had welcomed him with the words “hello brother”.

Haji-Douad Nabi

We were to learn so much more about Mr Nabi and his family in the coming days. Sadly, before the attacks we had had little contact with the Muslim community through our reporting.

What coverage there had been was focused on the tiny group of people considered Muslim extremists. We were looking the wrong way. We had failed and were starting from scratch – trying to build relationships in the most awful circumstances.

All great journalism is about connecting with people, telling their stories with due respect and care. Great journalism and leadership needs empathy.

From the field

We first hear about the attacks when one of our reporters drives past on the way to pick up her boyfriend from a medical check-up.

Reporters Logan Church and Conan Young rush to the mosques. Logan arrives at the first mosque before the police roadblock is set-up.

Logan Church at the scene of the shooting

“I then saw a man walking up Hagley Park in a suit but in bare feet. He was shuffling along, looking at the ground. He looked like he was in another world. I went up to speak with him, shouting for our video journalist Simon to follow…he told us 50 people were shot dead on the floor of the mosque. He was the first interview done post attack… other people started coming out of the mosque. It looked like a slow motion zombie apocalypse, for want of a better simile.

“We interviewed and spoke to several of them. Almost everyone was shocked and crying. I remember one man we interviewed because he had blood all over his hands. Live crosses continued. We were not getting any official confirmation, but I had been told that the attacker had uploaded a video. I watched it. It, tragically, gave us confirmation.

“Ambulances went non-stop backwards and forwards for hours. Later on we then went through to the hospital, and continued live crosses. I went home at midnight. The next few days were rough for me to be honest.”

Conan sees ambulances heading in the direction of the second mosque, close to his home. He races there.

Conan Young

“I could see one injured person lying on the ground being helped by others. Ambulances were coming and going. I could tell things were bad inside as one ambulance stopped to check on the person lying on the ground and then moved on. I assume because there were people in greater need still inside the mosque.

“There was a lot of activity including heavily armed police, AOS (Armed Offenders Squad) and plainclothes police wearing face masks. Police were using a battering ram to break a window in a building in front of the mosque. I went to air soon after arriving, telling our afternoon’s presenter what I was seeing. The next priority was taking a few photos of what was going on and getting these through to the website. I then went to talk to a number of those who had managed to escape the mosque who were milling about near the cordon. Those who were inside mostly weren’t wearing any shoes, these having been left at the door before Friday prayers.

“One man’s story was so strong I called back into programmes and put this man straight to air, talking first to the presenter and then passing this man the phone. He told of being shot at inside the mosque and there being a number of dead and injured. He still hadn’t been able to find his father at this stage and was very worried.

“Soon after a group of survivors who were being looked after in a shop over the road from the mosque were led out past the cordon and put on a bus. This included the Imam who was covered in blood from having helped the injured. I managed to speak to one of the people being brought out and got a bit more of a picture of what had gone on.

“People at the cordon were looking at the live streamed video of the shooting showing the carnage at Al Noor and rumours were flying of the hospital being targeted and bombs being discovered in other parts of the city.”

What do we do?

Back in our Wellington and Auckland offices, where the majority of our staff are based, quick decisions have to be made but the coverage also needs space to get underway.

We have a series of short conversations and small meetings, with a larger editorial meeting scheduled for in an hour.

The first step is letting the entire business know a major news event is happening and staff on the ground are not to be contacted except through their bureau chief.

The radio programming schedule – which at that time of the day is not normally news – is broken into and live coverage starts there and online.

We ask for volunteers to head to Christchurch and work through our other offices over the weekend. Everyone wants to help, so a couple of people organise them.

Everything else stops. All staff are on the story and we start breaking out angles for them to follow based on the initial information.

The story list is centrally held and worked on – of greatest importance is information from the scenes and victims. Investigating the shooter; the political reaction; communications from the emergency services are handled by staff in other locations..

Key senior staff move to the same set of desks. Physical proximity is helpful. Decisions are being made minute-by-minute.

After the first hour we hold an editorial meeting with people from across the business – including those in finance, studio and technical support, the people who help get things done – to assess where we are at and what we need to do.

This is the first, and incredibly important, place to help set the tone of our coverage, to talk about respect for the victims, supporting our teams and ensuring they are safe. To emphasise what I expect from our senior leaders, how they work together and with our people. You can’t show empathy without taking the time to understand what others are going through.

In these situations, leaders need to bring calm and consistency when all feels unstable.

Adrenalin gets people through the initial moments and days but you need to talk about how big a story it is and that it will take months to cover. It helps people process the situation more.

Leaders need to ensure people have the support and room to do their work. Forget about what other media outlets are doing. Tell your staff this too. Have the strength to focus on what your people need and the stories you are trying to tell. If you’re slipping into the habits of ‘journalism at any cost’ you, the victims and their stories all lose.

This kind of coverage has an impact on everyone. You should be encouraging the sharing of emotion. Don’t be scared of people’s vulnerability – embrace it and your own. We took the practical step of immediately setting up counselling for staff. At times like this, trust comes from being empathetic.

Ultimately, you need to talk about values, not just the nuts and bolts of coverage. They give shape to everything. Our mantra was clear – it’s about the people. They are us.

Our coverage

Following the meeting I quickly communicated to the business the initial approach we were taking. At this stage we did not know there was only one gunman. Here’s what that note said:

“We need to exercise great care when reporting details of the terrorists’ propaganda, justifications and arguments. We must not be their mouthpiece or platform. We do not want to be repeating their manifesto.

In particular, unless expressly approved by the editor-in-chief, we will not broadcast or publish audio or video of the massacres or of social media posts in which they discuss their beliefs or plans.

We must still, however, cover the story fully, rigorously and responsibly.

We will judiciously provide audiences with verified information about the attackers’ activities and backgrounds, motivations and life stories and we will summarise and contextualise the coverage.

When talking to victims/witnesses/families/the general public keep in mind how much trauma they have been through. We don’t want to be seen to be re-victimising people who have suffered so much already. If in doubt, escalate up.”

In the coming days and weeks I re-emphasised time and again the need to empathise with those affected and each other.

Here’s another excerpt from a communication to staff:Last night at dinner I was talking to my family about the day in Christchurch and the conversations with our team down there. During this, my daughter asked what a “death knock” was. My wife did a lovely, honest, job of explaining it but it was yet another big reminder to me of what we ask of our staff and the victims’ families.

I have said it many times already, but this is as tough as it gets and we need to constantly remind ourselves. We support our people and are respectful of the wishes of those affected by the tragedy. Obviously, we continue the counselling put in place around the business and I encourage you to keep talking and sharing with each other.

Our coverage will start to shift gear in the coming weeks from the stories of the immediate aftermath to the big questions which need answering and the people trying to rebuild their lives. To maintain good relationships with these people we must tread very carefully in the field and in editing the material provided. This will require moving along with them and not trying to hurry them to suit our always fast-moving timetable. RNZ’s coverage will last months and years…

I said it in Christchurch yesterday, but I have never been prouder – the work done to date, in such testing circumstances, has been absolutely world-class. Thank you to everyone involved and those who continue to support our people.”

Important practical steps included ensuring people were fed and watered; they got breaks and days off – they worked super hard though. Staff on the ground in Christchurch were rotated in and out to avoid it becoming overwhelming. When they were, we checked on them regularly. I made myself available to talk at any time. I communicated what was happening at least twice a day – pointing to great work and flagging up important milestones. I hugged and consoled staff. I showed my own vulnerability.

Keep adapting

At the end of day one we have been live broadcasting and blogging for 10 hours including six of that visually. We have details on the first victims, name and give background on the shooter’s life and travels (without detailing his manifesto) and tackle the political reaction. Our live coverage continues through the night, with Saturday’s schedule completely rebuilt.

We start to think about the days and weeks ahead. We have more staff in Christchurch, with a great mix of senior and younger staff, but what becomes clear is we need to avoid being caught up in our and the formal information machine.

What do I mean? Most media outlets, and RNZ is the same, are good at organising their day – it’s done by deadlines for bulletins, packages, web writes, slots on-air etc. The official government media operation makes this worse, with a daily schedule of press conferences.

We risk falling into the trap of letting these dominate. It becomes apparent that reporters are caught between the enormity of the tragedy and RNZ’s normal demands. What they need is some space to build relationships.The team in Christchurch start to separate out the tasks and resources around our mantra – it’s about the people, they are us. We are very clear about not doing “quick hit” stories with those grieving. Staff need time to talk decently and kindly to people.

During such events there is more than enough news. The idea is to go for the best work you can produce, not the most. It’s also about grouping the right skills together – no one reporter can do this by themselves and having them work in teams achieves better results. It gives them inbuilt support too.

So everyday we split our resources into different groups – people are given time to build relationships and follow unique angles; some are on the daily round of important official announcements; others research deeper angles at a national level and build new material.

The senior managers who spend time in Christchurch try to think about “buying reporters time”, so they could follow a hunch or spend a long time with someone.

It does work. There’s still so much to do but the team tell wonderful stories with care and respect. Staff build relationships with victims and families.

At the times when this doesn’t work, as a leader you need to accept it and move on.

The aftermath

Five weeks after the attacks, I left RNZ. I had resigned in January, with plans to head overseas and travel with my family.

I was immensely proud to have been involved and, because of people’s incredible work, more emotional to leave.

A few months later I was asked to present a summary of RNZ’s coverage to a journalism conference in Turkey. As part of that I went back to some colleagues for feedback. They are the ones who did the truly heavy lifting. Their views and experiences carry an immense importance. It’s revealing:

“I was worried almost all the time about the reporters’ welfare. They were talking to grieving people every day. They were thinking about the unspeakable. We were working in a tiny office. Long hours. But in those first few days people worked superhumanly. The stress and fear actually came later when everyone stopped.

“What worked really well was the relentless focus on reporters’ welfare and that constant focus on telling the stories of the victims. It was like a mantra when people were tired; tell the stories of people involved. It was simple and true and decent and right. And we all tried to follow it.”

“I was always impressed by the kindness and empathy of the reporters. But also their strong sense that they often knew little of the cultural backgrounds of the people they were speaking to.”

“There were so many stories to tell and although it was overwhelming and trying at times, I felt this desperate need to tell them. Many of us, I think, were in work mode, a lot of what we were seeing and hearing didn’t sink in until we were separated from the situation. I spent most of my days door knocking. It wasn’t pleasant but every family I met was kind and welcoming, which I remember really caught me by surprise. I remember at one point wondering if I was too young to be covering these stories. I’d just interviewed a girl my age (20 at the time) who had lost her dad. That really stuck with me.”

“There was a lot of support in the newsroom – I don’t think I’ve ever hugged so many colleagues. We had a counsellor in the office as well but I had no interest in speaking to her at the time. She didn’t understand what any of us had experienced, so I felt more comfortable speaking to others at work about what I had seen/heard etc.”

“For about a month we were regularly reminded to get support and sing out if we were struggling, but then people started moving on. Different stories were creeping into the news and for those of us outside of Christchurch, we were covering general news again (with the odd exception). That was when the adrenalin wore off for me and things got tough. I’d say I’m struggling with what I experienced more now than I did at the time. I’ve had Christchurch related nightmares and have found some stories really tough. This has really taken me by surprise… I’d suggest that anyone covering something similar should create a clear line of communication with their manager as soon as things have quietened down. Tell them if you’re struggling, ask for time off if you need it and be honest. I know a few of us have done this!

“I’ve nicknamed it the creep. Where, months after an event, you start to notice changes in yourself and the way you interact with others. I became impatient with people and picked fights when I noticed small injustices around me. I was also angry and didn’t know what to do about it. I pushed people away so they wouldn’t be on the receiving end of my frustration when it was undoubtedly about a particular man and a particular incident that I could do nothing about. I withdrew from my closest friends when they couldn’t say or do the right things.”

“I’m constantly working on all of these things. RNZ provided great immediate support after March 15 and continues to fund counselling sessions for those affected. I felt that I was listened to in March and the company catered for my needs as best it could. Four months on however, I feel the cracks are starting to show as this support has tapered off. The adrenalin has well and truly worn off and, as we settle back into reality, those who reported on the ground have been left to make sense of what happened.”

“The main thing companies can do for reporters covering trauma is to foster a safe environment for open kōrero about how they’re feeling. It’s isolating enough having to report on such an event (you return to your normal life and no one quite understands what you’re up against) so it’s important to feel like it’s safe to reach out to your colleagues, speak about your mental health and ask for help when you need it.

“There’s no denying it has affected me more than any other story I have ever worked on. It feels personal. As we approach the six-month anniversary I still don’t know if I have processed what’s happened.”

“As time went on, I suddenly became the ambassador, the spokesperson, the Muslim directory, the Islamic encyclopaedia, the religious and cultural expert… you name it, I was it. I think everyone was fully aware of how much they were asking of me, but that didn’t stop it from happening. I was happy people were relying on me, but I wished to share that weight of being the only Muslim journalist with at least one other person.

“I was surprised by the amount of attention and care. I guess even I am just so used to minorities like Muslims in New Zealand being ignored.”

What does it all mean?

A famous journalism quote says our work is about speaking truth to power. I don’t believe this is enough.

The Christchurch attacks taught me yet again that we need to better represent the under-represented. We also need people from these communities to be encouraged into journalism.

The current Covid-19 crisis is a perfect example. Those with the least voice will suffer the most.

Often, newsroom leaders risk becoming blase about what their people have to do. It’s a way to insulate yourself. But the impact of trauma on journalists cannot be ignored any longer and responses need to be tailored and over much longer periods. We need to understand how different events affect them.

We can’t keep people in this crucial industry, which is suffering many blows from other factors, if we don’t care for them.

When I started as a journalist, such thinking would have been dubbed “soft”. You got on with your work and buried away the side-effects. This cannot be the way anymore.

Journalism is about understanding people. Leadership is too. We need to form a relationship with people to tell their stories with due respect and care.

The best journalism can’t happen if you aren’t leading your people with similar empathy. It’s never more true than when covering disasters or tragic events. You need to understand how it affects your people and yourself.

It means being vulnerable enough to welcome people’s emotions and share your own. If you can’t do this, it’s going to get a lot tougher.

Author photo:

Glen Scanlon was the head of digital and then head of news and digital at RNZ between November 2014 and April 2019. He has been a journalist for 21 years, working in New Zealand, the UK and France. He is currently contributing to RNZ’s Covid-19 coverage and working on VoxPop NZ, a digital journalism start-up.

Main image: Tributes and flowers left outside Al-Noor Mosque in Christchurch after the terror attacks. Photo: RNZ / Isra’a Emhail