Ethics and Self-Regulation: Saving Time, Money and Keeping Journalists Out of Court

Chris Elliott

More than 30 judges and journalists gathered in a conference room in the heart of a sunny Sarajevo last week (24 January) at a seminar to discuss media ethics and freedom of expression at a two-day seminar to strengthen judicial expertise.

For anyone used to the usually more distant relationship between judges and the press in most countries in Europe, the frank and fearless exchange of views between the two might have raised an eyebrow.

However, it was not out of place in a city that saw one of the longest sieges in history 25 years ago after the collapse of Yugoslavia, which led to this young but determined nation of Bosnia Herzegovina (BiH).

But the fledgling state is still facing tough challenges. Its political landscape remains divided along ethnic lines and some media reflects what one contributor to the seminar called “1,000 years of tribalism” that hampers efforts to create national unity.

This meeting, organised by the Council of Europe and BiH press council as part of Europe’s JUFREX project, focused on how these problems have created headaches in Bosnia for lawyers and journalists alike.

I was there on behalf of the Ethical Journalism Network (EJN) to make the case for the need for professional ethics in a digital age and the importance of news organisations differentiating between fact and opinion.

The messy and potentially dangerous confusion of the two is growing all over the world. It is particularly prevalent, but not exclusively so, on the web where social media blurs the lines. However, it is an exceptional problem in BiH, which has a population of 3.5 million people and 173 active libel cases, said Borka Rudić, Secretary General of the BiH Journalist Association.

Many of these cases involve highly sensitive politicians confusing criticism with factual inaccuracy and journalists feel that the courts should have a better understanding of the difference.

The association has a panel of 10 lawyers who give free legal advice to their members and this problem area takes up much of their time.

One of the themes to emerge from the discussion about such high rates of litigation was mediation before a court dispute – what can be done to resolve a complaint before it goes to law?

I discussed my time as readers’ editor of the Guardian and how the independence of the role is key to making it work successfully as well as the need for journalists to work to, and be judged by, a professional code of ethics. Self-regulation when it is independently rooted and trusted is one way to save time, money and anguish when dealing with a complaint.

This was also a method of resolution emphasised by Amir Kapetanović, a judge of the district court in Banja Luka.

Both the judge and I discussed article 10 of the European Convention on human right, which enshrines freedom of expression, and how it is interpreted by the courts.

Article 10 says:

- Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

- The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

If you are a journalist you tend to focus on the first half, as I did. However, the judge concentrated on what the second section means when cases come before the courts. And his focus is important for journalists to understand.

Both of us looked at the article through the prism of a particular case, Delfi AS vs Estonia.

The background to the case is that a leading Estonian news portal, Delfi, published an article in 2006 discussing the implications of a shipping company’s decision to move its ferries from one route to another. This involved potentially breaking ice at points that may be used as ice roads.

The article attracted about 185 comments below the line, of which 20 contained anti-semitic, abusive and offensive content, aimed at a senior executive at the ferry company.

As soon as Delfi became aware of the complaints they took them down but this was some six weeks after they had been posted. Although Delfi had acted swiftly and according to their takedown policy the targeted executive, known only as L, decided to pursue them for damages for the six weeks they were up on the site. He won and Delfi was ordered to pay €320 in damages.

Delfi battled through the courts on the basis of article 10 ie their right to freedom of expression, all the way up to the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights.

Prof Dirk Voorhoof, of Ghent University, writing on the Strasbourg Observers blog, on 16 June, 2015 just after the Grand Chamber’s judgment wrote:

“The Grand Chamber has come to the conclusion that the Estonian courts’ finding of liability against Delfi had been a justified and proportionate restriction on the news portal’s freedom of expression, in particular because the comments in question had been extreme and had been posted in reaction to an article published by Delfi on its professionally managed news portal run on a commercial basis.

“Furthermore the steps taken by Delfi to remove the offensive comments without delay after their publication had been insufficient and the 320 euro award of damages that Delfi was obliged to pay to the plaintiff was by no means excessive for Delfi, one of the largest internet portals in Estonia…

“In essence the news portal is found liable for violating the personality rights of a plaintiff who had been grossly insulted in about 20 comments posted by readers on the Delfi news platforms’ field for comments, although Delfi had expeditiously removed the grossly offending comments posted on its website as soon as it had been informed of their insulting character… Regardless of a technical system filtering vulgarity and obscene wordings, regardless of a functioning notice-and-take-down facility, and, most importantly, regardless of an effective and immediate removal of the offensive comments at issue after being notified by the victim about their grossly insulting character, the Grand Chamber shares the opinion that Delfi was liable for having made accessible for some time the grossly insulting comments on its website. The Grand Chamber agrees with the domestic courts that Delfi was to be considered a publisher and deemed liable for the publication of the clearly unlawful comments. The Grand Chamber is of the opinion that Delfi exercised a substantial degree of control over the comments published on its portal and that because it was involved in making public the comments on its news articles on its news portal, Delfi “went beyond that of a passive, purely technical service provider” (§ 146).”

In my session I argued that article 10, so often the journalist’s friend – after all it led to one of he most important protection of sources findings in post-war Europe, the Goodwin ruling against the UK – may be less durable in the digital world. The Delfi decision is of concern to journalists seeking to build a lively community below the line where the news organisation has operated a takedown policy that has, hitherto, been considered effective in keeping publications on the right side of the law.

Judge Kapetanović, in his session, argued that the decision by the Grand Chamber showed just how effective article 10 can be in ensuring an individual’s rights as well as freedom of expression. Same case, same article 10, different views of what the outcome means. We live in interesting times, and in Bosnia, where the tectonic plates of politics and journalism regularly collide, the media have to be more aware than most of the risks as well as the benefits of article 10.

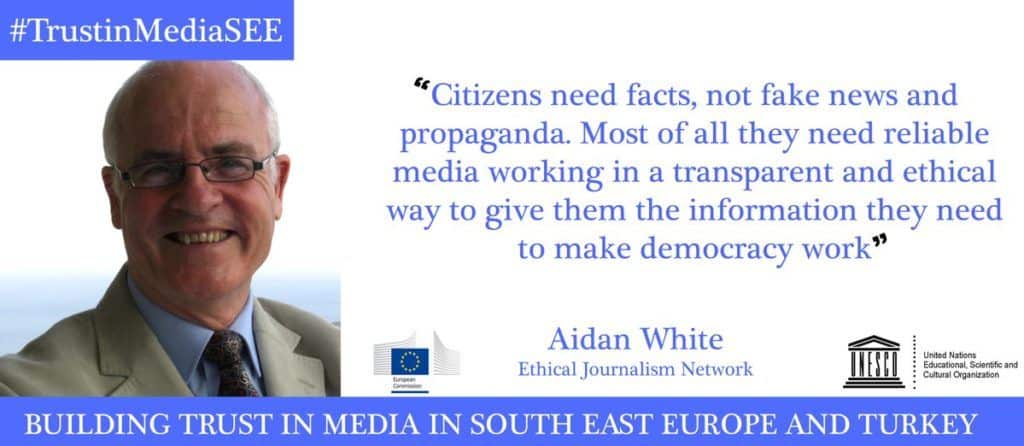

For more about the EJN’s work to promote better self-regulation in South Eastern Europe read about our ongoing project with Unesco and our reports on corruption and self-censorship and trust in media.

Main photo: Ethical Standards and Freedom of Expression: Free and Responsible Journalism and Good Judicial Practice. 25 and 26 January 2018 (Photo: Council of Europe)