Refugee Stories that Need to Be Heard

This is an edited version of a speech given by EJN board member and former Guardian readers’ editor Chris Elliott to the University of Tampere on 14 October 2016. A shorter version of the speech was also given to an event on migration coverage organised by the Union of Journalists in Finland earlier the same day where Chris contributed to a panel on “Stories that Need to Be Heard – Refugees in the Media”.

Chris Elliott presenting the EJN migration guidelines in Helsinki. (Photo: Finnish Institute)

I am delighted to be able to talk to you about the coverage of what I believe to be as big a story as any to emerge in the early 21st century – the displacement of tens of millions of people.

I think that the coverage of migration in this sad and brutal time is as crucially important as coverage of the economy, the Middle East or climate change. Never has there been a greater need for cool, calm and collected journalism, which should be painstakingly fair and accurate.

As I know only too well, coming from the UK where we have just had a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, this is not what readers are getting from many parts of the media.

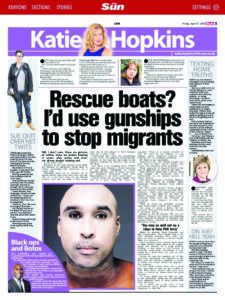

Here are just a couple of examples of the kind of problematic language being used in the UK:

Katie Hopkins was a columnist for The Sun – she now works for The Daily Mail. In an article last year about migrants she used the term “cockroaches” to describe them. This echoes terms of abuse used by the Nazis and the architects of genocide, as my colleagues in the EJN pointed out.

She was reported to the police but no action was taken.

Last Friday it was reported that The Daily Mail had breached the Editors’ Code with a front-page story published a week before the EU referendum vote that was headlined: “We’re from Europe, let us in”. But as a story on the UK Press Gazette website made clear, they weren’t. They were from Iraq and Kuwait.

According to the Press Gazette:

The full Daily Mail headline read: “We’re from Europe – let us in! As politicians squabble over border controls, yet another lorry load of migrants arrives in the UK.”

The Daily Mail said that the story was based on copy provided by a reliable news agency and the reporter tried to verify it at the time. This was not accepted by the Independent Press Standards Organisation, which adjudicated on the complaint from a reader.

The IPSO code committee said in its ruling:

‘…in the video, the individual in the lorry could clearly be heard telling the police that they were from Iraq and Kuwait. This was repeated by the police officers present, and the committee did not therefore accept the explanation offered for the error in transcription.’

These tensions of language and tenor are well reflected in the pages of the excellent report launched today by the Finnish Institute in London and the Finnish Cultural Institute for the Benelux countries: “Refugees and Asylum seekers in Press Coverage 2016.”

It is a fascinating and admirably detailed piece of research, although I would have liked to see more popular papers in the mix.

The numbers from the report are interesting. It says:

‘The number of refugees and asylum seekers has significantly grown during the past five years. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 10.4 million people had fled from their homelands by the end of 2011. By the end of 2015, the number had already reached 15.1 million, the highest level in 20 years. These figures only include the refugees under the mandate of UNHCR and don’t count in the people under the mandate of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). In other words, the number of refugees grew by approx. 45 % in three and a half years. The main cause of the drastic increase is the Syrian War.’

I think that the fact that the number of asylum applications for Finland is the highest in proportion to the population of the three countries studied may provide clues as to the nature of the reporting, which is localised, with a focus on the Finnish-Russian border.

It may also go some way to explaining some of the physical signs of the nation’s concerns like the appearance of street patrols. Maybe it’s also a possible reflection on the age-old equation: stranger equals danger.

But in all papers the report shows a Eurocentric focus, amplified by the emphasis on the voices of politicians rather than the people most directly involved – the migrants themselves.

I am very interested in the language used to describe migrants by each of the papers. As the former readers’ editor of The Guardian – a kind of internal ombudsman who deals with complaints from readers – I have a vested interest in the terms used to describe migrants, often the subject of complaints. Throughout the report it is clear that politicians are willing to use inflammatory terms when it suits them. I was particularly struck by a passage in the report about a Belgian newspaper:

‘De Morgen is aware of the definitional and value-based nature of the choice of terminology and wording.

This is especially apparent in an article where the writer has compiled different expressions publicly used by prominent people, European politicians for the most part, in reference to refugees and asylum seekers. They include, for example, asylum seeker, molester (Asielaanrander, Theo Francken), penalty payment Afghan (Dwangsom-Afghan, Theo Francken), seagulls (Meeuwen, Louis Tobback), testosterone bombs (Testosteronbommen, Geert Wilders), trash (Tuig, Nicolas Sarkozy), flock (Zwerm, David Cameron), and fucking Moroccan (Kut-marokkaan, Rob Oudkerk). The article is headlined: Ditch those words!’

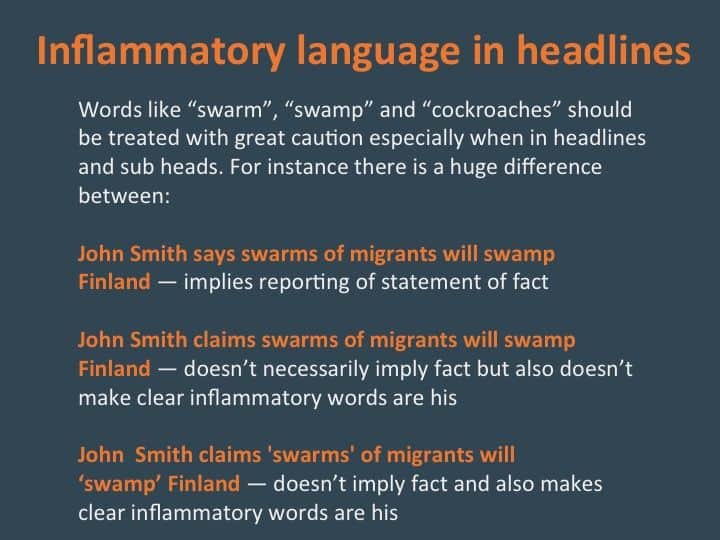

We are no better in the UK, as I said earlier. Prominent politicians – including the then prime minister – have used terms such as “swarm” and “swamp”. Journalists should handle these phrases with extreme caution when politicians seeking headlines use these words. And we have to remember that headlines in a digital age are often the only thing a reader sees – any context in the main body of the article may never be seen.

The Guardian received a number of complaints about the use of the term “illegal immigrant”, which started a debate that ended in the virtual eradication of the term within The Guardian.

I explained the background to these complaints and the ensuing debate in a column:

‘…The use of “illegal immigrant” is a term human rights activists would like to see ended, as in this example in the Guardian in a story published on 30 July, headlined “David Cameron criticised for PR stunt in home of suspected illegal immigrants”. One paragraph read: ‘The government has previously been criticised for sending out vans with billboards telling illegal immigrants to ‘go home or face arrest’. The pilot project, which resulted in 11 people leaving Britain, was not extended.”

Following that story, Lisa Matthews, the coordinator of Right to Remain – not a group dedicated to remaining in Europe but one that campaigns for migrants’ right to remain – wrote to The Guardian expressing her concern about the use of the term:

‘We are disappointed the Guardian has chosen to use the terms “illegal immigrants” and “illegal migrants” in its articles (most recently, ‘David Cameron criticised for PR stunt in home of suspected illegal immigrants’, 30 July 2014),’ she wrote.

‘As a human rights organisation working to support migrants (including undocumented migrants whose right to stay in the UK has not yet been formally established), we are troubled by the paper’s persistent use of this phrase.

‘The term “illegal immigrant” is inaccurate and dangerous. Even in the case of someone deemed to have committed an immigration offence by not having the correct papers, the person themselves is not “illegal”.’

I agreed, and now, as the report states, we most often use “refugee”.

Let’s turn to how we can we improve coverage of migration in our everyday work.

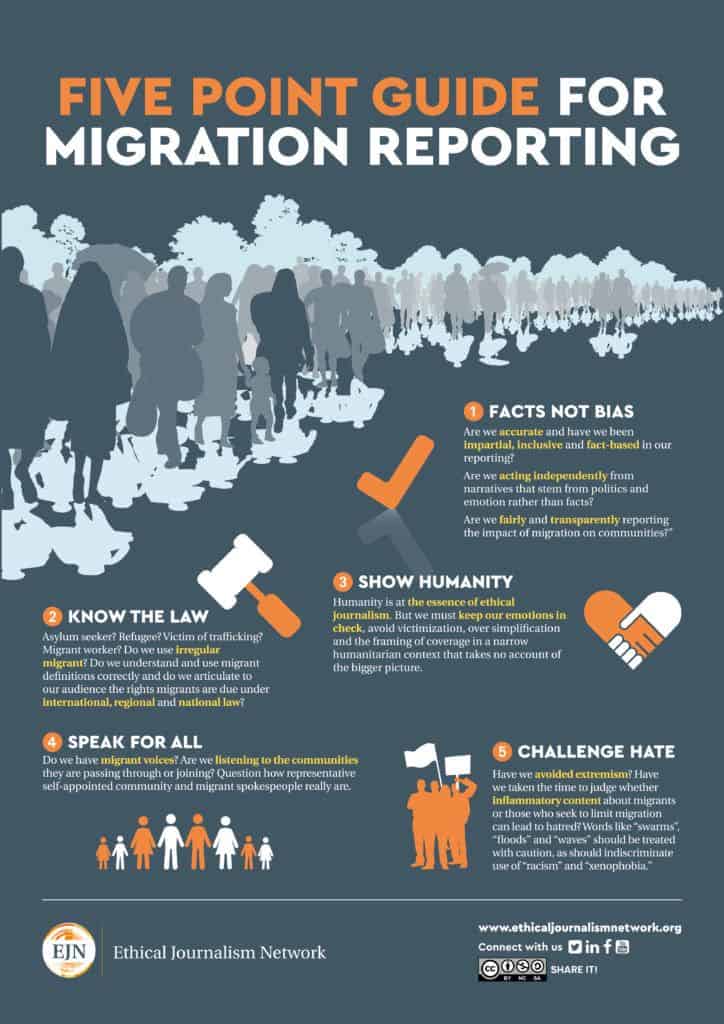

The Ethical Journalism Network, of which I am a board member, has just launched a 5-point guide for covering migration on the back of its own report into the coverage of migration in 14 countries – Moving Stories, published last December.

The EJN is a coalition of professional media groups from Europe and around the world committed to building trust in the media and promoting principles of ethical journalism, good governance and self-regulation in the digital age.

The researchers for the Moving Stories report found that despite many examples of excellent coverage, journalists often fail to tell the full story and routinely fall into sensationalism and propaganda traps laid by politicians.

‘The conclusions from many different parts of the world are remarkably similar: journalism under pressure from a weakening media economy; political bias and opportunism that drives the news agenda; the dangers of hate speech, stereotyping and social exclusion of refugees and migrants. But at the same time there have been inspiring examples of careful, sensitive and ethical journalism that have shown empathy for the victims.

In most countries the story has been dominated by two themes – numbers and emotions. Most of the time coverage is politically led with media often following an agenda dominated by loose language and talk of invasion and swarms. At other moments the story has been laced with humanity, empathy and a focus on the suffering of those involved. What is unquestionable is that media everywhere play a vital role in bringing the world’s attention to these events.’

While today we are concerned with Europe, Moving Stories also looked at the situation in Australia, where The Border Force Act 2015 (Cth) makes it very difficult for doctors and others employed by the Australian Government and contractors on Manus Island and Nauru (the sites of my government’s two offshore detention centres) to whistleblow about unlawful practices they witness. This has serious implications, quite clearly, for the capacity of journalists to uncover stories of abuse etc being committed in Australia’s name. This is compounded by the difficulty for journalists to acquire visas to visit those islands – journalist visas are around AUD$8000. This means there is effectively a media blackout on the treatment of asylum seekers and refugees in offshore immigration detention.

So, to help journalists navigate these tricky waters, the EJN has developed the guide as a tool for media to use when reporting on migration and to analyse news coverage.

EJN Five Point Guide for Migration Reporting

Too often the media accept the outrageous statements of political and community leaders as newsworthy without reporting them in context or challenging the impact of hate speech on migrants or marginalised groups.

Report the words said, that’s our job, but with care and context. As I said earlier, also remember that in the digital age the headline is often the only part of the story a reader will see.

All too often migrants are only seen in terms of numbers and as a security problem – try to resist that kind of group-think.

Context is the key – don’t forget the big US news agencies, which stopped giving major coverage to the pastor who kept threatening to burn a Koran.

This is not about censorship.

I believe these are a helpful set of guidelines in an area of reporting bedeviled by emotion and paranoia. They don’t cover every situation but provide a balancing set of principles against which you can judge whether a journalist has asked the right questions and whether his or her story is fair.

In addition I would add a few injunctions of my own:

Beware of the rush to publish. In a digital age there is a great deal of pressure to get it up now but this can mean all too often that fact-checking and verifying images is overlooked.

The use of images is a very difficult issue. One of the most arresting images, possibly the most significant in awakening the people of Europe to the growth in migrants risking death to get to Europe, was that of Aylan Kurdi.

Was it too intrusive to show the Syrian three year-old’s dead body on the beach or in other context?

This is what a senior production editor at The Guardian, Jamie Fahey, wrote about the decision not to use that picture on the front but substitute one with a policeman gently carrying him in his arms with just a little of the child’s face showing.

‘…The web story featured as its main image the picture of a solemn Turkish policeman gently carrying away Aylan’s body, while the arguably more vividly distressing picture of his lifeless body face down on the sand was used as a secondary image embedded beneath a warning to readers. As for the paper, the decision was made to run the striking image of human compassion – the policeman cradling Aylan – which was run on the front page and the second image much smaller on an inside page.‘

In the article Fahey quotes Katharine Viner, The Guardian’s Editor-in-Chief, as saying:

‘It was very important to us that we placed Aylan’s death in context, with some serious reporting about what happened to him and the broader picture of current political and social attitudes towards refugees across Europe, particularly in Britain and Germany. I still think it was right to use the pictures, but I might be wrong about that, and I’m aware that good intentions and serious intent are not always enough.’

Thinking time is the key, a precious commodity at any time in the newsroom, especially in a digital age, so we must use as much or as little as we have as best we can. One of the most difficult recent decisions at The Guardian on whether to publish or not to publish after a terrorist incident came after the killings at the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris and at a Jewish supermarket.

The issue was whether to publish an image of the front cover of the first Charlie Hebdo cover following the attacks.

Two decisions were key: one not to reproduce offensive cartoons of the prophet Muhammad that the magazine had published before the killings, and the second to show the front cover of the magazine produced afterwards, which also featured an image of Muhammad.

Both decisions divided readers. One wrote:

‘The publication [of the Charlie Hebdo front cover] was a completely wrong decision and … can do nothing but cause further insult and distress and increase tensions in an already volatile situation. Shame on you.’

Another approved of that decision, but thought we should have published the picture of the cover more than once:

‘You printed a postage-stamp size reproduction of the cover of Charlie Hebdo with the comment that ‘its news value warrants publication’. Good. But [in other articles] you describe the cover without showing it. What a shame. In my view it is a poignant and dignified response to the murders of their colleagues.’

Both decisions also divided The Guardian staff. However, of the 24 people who responded to my email canvassing opinion, most believed we had got it about right. There was a lot of internal discussion between editors and staff.

Some of those discussions took place at a morning conference that lasted an hour and was attended by around 100 members of staff. The subsequent decision not to publish any of the earlier Charlie Hebdo cartoons featuring Muhammad was explained in an editorial published in the print edition on 9 January, and online the evening before, which said:

‘The key point is this: support for a magazine’s inalienable right to make its own editorial judgments does not commit you to echo or amplify those judgments. Put another way, defending the right of someone to say whatever they like does not oblige you to repeat their words…’

Those words, written by the then Editor-in-Chief, Alan Rusbridger, contain a key principle that I think binds the coverage of this terrorist attack and the coverage of migrants: the need to remember that just because we can we don’t have to.

I will reiterate that it’s important not to censor what has happened, what has been said, but I think the key is to remember that we can and should choose how we do so. We are journalists, not stenographers.

When we think of migrants we should remember what our colleague Hussain Kazemian, a journalist from Afghanistan now a refugee in Finland, said a little earlier this afternoon: ‘We came here to be surviving one more day [at a time]’.

For more on media and migration read our Moving Stories report.